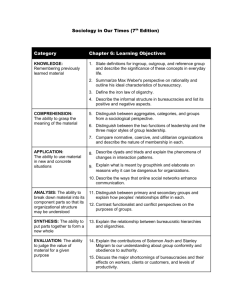

Intergroup Behavioral Strategies as Contextually Determined

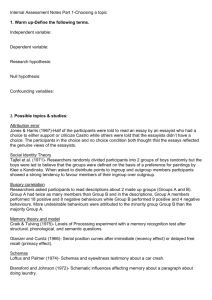

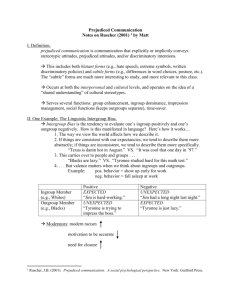

advertisement