This film , many others about the holocaust does not address the

advertisement

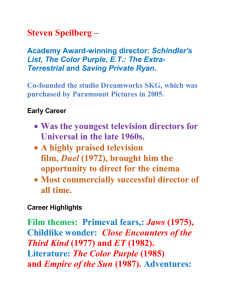

1 Ben Roth On Schindlers’s List To view the Holocaust from within a group psychoanalytic frame it is necessary to treat the actual Holocaust in the manner of memory; to distinguish the one remembered - from the mythic or metaphoric one. The actual Holocaust left in its wake questions about silence, criminality and the long term effects of trauma on individuals, families and groups. On the other hand it left unanswered questions about the appeal of the Nazi as a political (group) movement. It also left behind less significant questions about whether something as profound as the Holocaust can be portrayed in a narrative form. The eloquent plea that the historical Holocaust story be told (Weisel1960) is held in a paradox since it is doubtful whether words, art or cinematic images can convey any part of its actual meaning. Further complicating this issue is a necessary distinction between the actual people, historical events and the transmission of trauma and defenses from generation to generation. In focusing on this American film, particular attention is given to the special appeal of certain kinds of leaders coupled with America's underlying ambivalent attempt to unhitch itself from anything European and therefore historical (Roth, 1993.) 2 The Film “Schindler’s List” seen through the prism of Leadership Styles. In this paper I will illuminate certain group dynamic aspects of the film “Schindler’s List and perhaps of Spielberg’s other film efforts. It is not my intent to either criticize or honor the film, nor do I intend to minimize its inaccuracies, cinematic license nor divergence from the source material or historical facts. Others have better credentials to do so and have done so already. (See Gourevitch, 1994 for a critique of the film and Crowe 2004 for recent research on Schindler.) It is my hope that this endeavor exist in harmony with these other efforts while demonstrating that dynamic group meanings are discernible operating as an organizing principle in the structure of this film. Moses' (1993) suggests that affiliation determines perception in writing of these historical and emotional events, in addition I suggest that Bion’s concept of vertices (Bion 1970) also determines discovery and affiliation while I align myself as someone not directly affected by the Holocaust All film making is a complex group process with a cinematic end product produced by a variety of people performing group tasks. What role these leadership group dynamics played in real life or in the construction of the film must remain hypothetical; however I believe there is something to learn and gain from this form of analysis. Film may be viewed as a form of articulated stimulation whose complex task is to form a narrative that allows social and political meanings to be discovered. The interplay of film sound and imagery stimulates patterns of associations in the viewer. Yet the film is experienced as outside of the self that allows it to communicate into a mental space that fosters the experience of actual and virtual at the same time. Spielberg’s film, taken from 3 a book with the same title, is primarily an American film, informed by a perception and psychology that both Americanizes the Holocaust and fits it into a melodramatic structure utterly acceptable to American film audiences. Schindler's story, when compared to the solitary story of the survival of V. Szpilman portrayed in the autobiographical “The Pianist”(2002), directed by Roman Polanski 1 satisfies the melodramatic moral needs of an American movie by telling an uncomplicated story of individual conversion; a seeming conversion of a man of indifference to others and hollow self-interest who inexplicably develops an empathic relationship with the people he has saved and in so doing develops an altruistic sensibility. From a psychoanalytic perspective, it is a story of a manipulative narcissist who (seemingly or temporarily) develops empathy for others. The character of Schindler taken by it self is an exception to the usual kind of hero in a Spielberg film. (See appendix ) Narrative films set in the holocaust do not address “The Holocaust” as a specific event, rather it is one that uses a narrow lens to reflect on a wider historical process; in this case the tragedies of the Jews in Krakow is a back drop for the unfolding of parts of Oskar Schindler's story. From a group dynamic perspective the Jews on Schindler’s actual List become his horde, his group, his audience. And Schindler is the leader of the group: a group Schindler first exploits as a manufacturer and profiteer, then leads, and ultimately through a seeming personal conversion he comes to protect as the war ends. When I initially viewed this film, I was immediately aware that from the perspective of 1 Polanski, unlike Spielberg, is a Holocaust survivor. He and his father survived the extermination of the Jews in Krakow. Pawel Edelman's camera work in “The Piano “is moving and he has brilliantly captured the dark sadness and hopelessness in the visual canvas in an effective way. One wonders what kind of “Schindler” film Polanski would have created if he accepted Speilberg’s offer to direct “ Schindler’s List “ 4 leadership and group analysis the unfolding of the story of Schindler can be recast by the question of who shall lead the group. Subsequent viewing of the film substantiated this group perspective that there are three different kinds of group leader in this film. War and war films In the following I will situate the Holocaust film as specific subgenre of the War movie so that I may make comparisons of articulated styles of leadership. Freud (1921) viewed the Army as one of the natural social groups. Being in a war temporarily and often permanently transforms the personalities of participants into interdependent social group structures of soldiers and civilians. Simply put, army’s at war are large hierarchical groups in combat usually usurping other social systems and accounting for the death of thousands of people. There is no grace to war and morality is often the first destroyed innocent bystander. There is little humanity in its goals and personal demands and yet the group bonding of men who face danger together is intensely strong and long lasting. Chaotic or situationally induced acts of violence are commonplace and acceptable usually occurring within group behaviors while simple every day acts of humanity are unusual under fire. Life as a captive may maintain some humanity, often some affectionate group affiliations, and some degree of choice. Captives, soldiers and civilians while different forms of group structures with differing moral cultures, have in common the wish and the need for the creation of a group leader. From an analytic perspective the leader's role in these different groups is the same: to reduce anxiety and to offer hope. As an example from a recent film Hotel Rwanda (2004), if the viewer can step outside the horrific images of genocide, Paul Rouseabangina portrayed by Don Cheadle, starts as a modest man who is 5 converted into a leader of courage and action by the genocidal acts around him, giving hope and direction to other people who flock to him. From a perspective of the character structure of a leader, he is a man converted by altruistic motives (Staub, 2005) to become a leader. Generally speaking filming war is problematic, and it is unlikely that films can capture the uncertainty, chaos and random destructiveness of actual warfare with anything close to either the reality or the feelings that accompany these acts. Spielberg has come closest to capturing the murderous intensity of battle in the opening sequences in Private Ryan. Filming concentration camps poses similar problems and Spielberg was not as successful in that films creating a reality based image of death factories. American War Films "War," says Schindler "brings out the best and the worst of people." American war films in general reveal attempts to engage in a discourse with the psychological changes produced by war on men. American war films have their own development from the propaganda films of early WW 11, the heroic middle and late phase films, and the ambivalent and often anti war films of the post Vietnam era. One underlying unifying psychological question raised in all these films is how war affects men, how it changes men, and the ultimate outcomes and manifestations of such changes. Inherent in the general question of how men are changed by being at war is the seemingly constant related question of how men assume leadership and command other men under conditions of war. For an example in another Spielberg film “Private Ryan” the sentimental image of the central character embodies the altruistic leader who cares for his men and sacrifices for the men under his command 6 An exemplary theme of the dual aspects of cinematic male leadership and representation of masculinity is often found in violent films made for male audiences; one example standing for many similar American films is Oliver Stone's war film Platoon. Platoon's narrative centers on the conflict of command leadership between opposing representations carried by the characters Burns and Elias: Burns is the male leader who is feared because of his destructive rages and Elias the male leader who cares for his men and is loved and admired by his men. In this war film the dark side temporarily triumphs with Burns' murder of Elias out of envy turned to disgust for his ‘weakness”. With Burns' cruelty already established by this act, his victorious destruction of Elias and over the sensitive caring male representation is not an acceptable outcome for American audiences. The required cinematic moral order is accomplished by a restorative assault on Burns in which Burns is killed as a cleansing act and a younger man takes over command. In such a manner Oliver Stone composes his iconic image of American soldiers and American war veterans. The American Soldier is a man psychologically changed by war and the veteran survivor as one who remains loyal and pure and is made wiser by killing (Newsinger, 1993). From a psychoanalytic perspective neither the evil-destructive or the loving male imago is understood or wished for as surviving in this kind of conflict. Spielberg seemingly is interested in moral conversion and sacrifice in his films. The personification of the conflict between the leader who is loved and the one who represents aggression and destructiveness or the "dark side" finds earlier substantive resonance in the iconic imagery accompanying Luke Skywalker and Darth Vader in Spielberg and Lucas’ Star Wars trilogy of men making war and fathers made bad. These dual mythic images of male leaders as loving and killing 7 are frequently the forces which make for heroic story telling and they reappear in Schindler’s List again in the forms of Schindler and Goeth, the concentration camp Commandant. In the following I will discern the roles of the three group leaders in this film as their representation bears on the psychology and function of group leaders : the aggressive-destructive narcissist Amon Goeth (Ralph Fiennes), the manipulative performing narcissist, Oskar Schindler (Liam Neeson), and the workgroup leader: Stern (Ben Kingsley) Schindler’s List When I first viewed this film it appeared that from a group analytic perspective this film contains two separate narratives. The first 80 minutes of the film the narrative follows and establishes Schindler's manipulative ascent into prominence along with his sexual and alcoholic appetites. His business success making enameled pots is marked by his supplying the Nazi’s with luxury items with the assistance of a man referred to as Stern. Schindler seems unaffected by what is going on around him and interested in his own success and his own sensual pleasures as he seemingly assumes his survival is not at risk. Between Stern and Schindler there is a different kind of relationship in which they appear to assume different interdependent roles in which Stern shrewdly tries to save as many people as he can by assigning them to Schindler work list, making them Schindler’s Jews, while Schindler becomes increasing dependent on Stern, an accountant, to manage all aspects of the business he bought with Stern’s help from desperate Polish Jews. In the scene in which Stern is rescued from the train going to the death camp, Schindler demonstrates his ability to understand the Nazi mentality by essentially bluffing his way to saving Stern by saying that the 8 men in charge will be sent to the Russian front by allowing Schindler to be insulted by their taking away an essential man for Schindler’s work. Rebuffed initially by Stern’s name being on the Nazi list, Schindler (without any authority) signs the list to take Sterns name off and Stern to safety. When Stern humbly apologizes to Schindler for causing a problem, Schindler utters the dependent and self interested phrase as the train being sent to the crematorium leaves without Stern, “What would have happened to me?.”. In terms of group leadership Schindler is the erstwhile self-appointed “King” of the Jews2, manipulative, narcissistic, libidinal, and living off their labor, while Stern is the effective Jewish Prime Minister essentially assuming the role of the work-group leader and literal human resource person concerned with saving as many lives as he can. Schindler's is self-proclaimed promotion selling his wares to the Nazi high command and Stern makes his list of Jewish workers names, runs the business, counsels Schindler and makes the products and events happen. The entire first 80 minutes of the film is about the emerging relationship between the reluctant Stern and Schindler, while the second half focuses on the relationship between Schindler and Goeth. Prior to Goeth's arrival, Spielberg continually makes this cinematic point from the opening sequence in which the camera follows Schindler dressing and winning over the Nazi's by gifts, to a later crises scene when he is financially bargaining for the release of his female workers wrongly sent to Auschwitz: Schindler sells Schindler or he sells his plan. In one scene he reads of a list of items to be acquired to bribe the SS (with invested Jewish money) from Poles. 2 King of the Jews is a term referring to Jewish history in which NonJewish Kings were appointed over the slave state of Jews. 9 Boxed teas are good, coffee, pate, uhm, kilbassa sausage, cheeses, caviar. And of course, who could live without German cigarettes and as many as you can find. And some more fresh fruit - they're real rarities, oranges, lemons, pineapples. I need several boxes of German cigars, the best. And dark and sweetened chocolate, not in the shape of lady fingers...we're going to need lots of cognac, the best - Hennessy. Dom Perignon champagne. Get L'Espadon sardines. And, oh, try to find nylon stockings. From the moment that Goeth enters the story in his command car, chooses the Jewish maid Helen because she has never been a maid and brutally kills the female architect in front of Jewish workers to demonstrate that Jews are expendable, the nature of conflict within the narrative changes to the ascension of Goeth as the brutal enforcer of extinction. Goeth is established as the destroyer of Krakow’s Jewry by an incredible scene in which he launches the destruction of the Jewish Ghetto with a speech of his genocidal intent to remove any trace of Jews from the recent 600 year old history of Krakow. The remainder of the film then deals with the intertwined relationship between Schindler and Goeth soon business partners, while Stern remains the background leader and work facilitator until the films’ end. In one scene after the business has been moved inside Goeth’s camp “During another hedonistic party at Goeth's villa attended by Schindler, he has been able to summon Stern from his barracks and speak to his accountant outside Plaszow's work camp gates. Stern prompts his incompetent ex-employer - now without his useful Jewish financial, organizational, or middleman skills - to remember the birthdays of their SS friends' wives and children, and the proper method of payoffs (without paperwork, invoices, or receipts) to the main administration and economics office and the 10 armaments board, the governor general's division of the interior, the chief of police's fees and black market contacts. Exasperated by the bureaucracy (as Goeth had earlier predicted) of working with the SS, Schindler threatens to give up: "It gives me a headache," he complains. Stern is concerned: "Herr Direktor, don't let the things fall apart. I worked too hard." Schindler then shares food scavenged from the party with Stern. It is difficult not to be sympathetic to the plight of the Jews in this film and the quick intercut scenes showing their fate are simple and well done. It is also difficult to not be sympathetic to the portrayal of Schindler and the conversion scene in which he overviews the destruction of the Jewish Ghetto from a hill over-looking the ghetto as its people are destroyed and the Jewish presence all but eliminated. Yet, I must turn away from that aspect of the movie to focus on another dynamic of the film. The other available structure of this film is formed by a represented conflict between styles of leaders of groups under unusual conditions or war and imprisonment in concentration camps. As with all such films the concentration camp assumes the representation as the final platform to death. On this bleak stage strut both Schindler and Goeth, somewhat protected and isolated from the reality of the suffering in their surroundings with Schindler spinning cocoons of privilege and libidinal excesses seemingly oblivious to the human wasteland around them. And Goeth is the embodiment of Hitler’s call for “A violent active brutal youth…. with no intellectual training” carrying out his extermination policy on whims. In one scene in Goeth’s villa overlooking the camps yard Goeth kills at random in the open field of the camp with a rifle, choosing his victims by chance, while later Schindler’s helps someone escape their obvious fate. This juxtaposition frames the emerging 11 differences between Goeth and Schindler. Goeth’s random killing captures the terrible uncertainty of life in the death camps where death appeared not as the work of human hands but as an impersonal destiny and a direct expression of Hitler’s wish for brutal death funneled through Goeth. In this arena Stern also functions, a composite figure drawn from Schindler’s historical lieutenants, to hold together the small community of workers in the factory who will endure under his protection and the shield of Schindler’s Machiavellian maneuvers. To frame the initial discussion of distinctions between Schindler and Goeth I will reframe Meloy’s (1988) seminal work on the nature of psychopaths. Meloy follows a historical psychoanalytic path that distinguishes two distinct types of psychopathic offenders (Meloy, 1988) : the destructive psychopath (violent) and the manipulative psychopath (libidinal). He believes these are distinct types that do not mix while Douglas (1995) refined this distinction of the destructive psychopath into two types, the chaotic and the organized. The German concentration camps with their dependency on lists and numbers would appear that they were run by the more plan-full and organized type of destructive psychopath; ones that constructed lists. These distinctions are important because they appear as archetypes in this movie representing linked types of leaders. Goeth is the disciplined military killer, giving orders expecting compliance, killing matter-of-factly while Schindler is the persuader, the manipulative sexual yet caring leader trying to prevent killing Is it possible that the audience is gazing on Schindler and Goeth as the symbolic twin faces of Fascism and Capitalism; of symbols of male manipulation and destructive violence? Are their faces those of an adaptive survivor and 12 malignant destroyer under war conditions? The scenes in which Schindler and Goeth drink and exchange perspectives on health, on forgiveness and about Helen (the maid) can not only be understood as reflecting their dual moral perspe Goeth: You know, I look at you. I watch you. You're not a drunk. That's, that's real control. Control is power. That's power. Schindler: Is that why they fear us? Goeth: We have the f--king power to kill, that's why they fear us. Schindler: They fear us because we have the power to kill arbitrarily. A man commits a crime, he should know better. We have him killed and we feel pretty good about it. Or we kill him ourselves and we feel even better. That's not power, though, that's justice. That's different than power. Power is when we have every justification to kill - and we don't. Goeth: You think that's power? Schindler: That's what the emperors had. A man stole something, he's brought in before the emperor, he throws himself down on the ground, he begs for mercy, he knows he's going to die. And the emperor pardons him. This worthless man, he lets him go. Goeth: I think you are drunk. Schindler: That's power, Amon. That is power. (Schindler gestures toward Goeth as a merciful emperor) Amon, the Good. Goeth: (He smiles and laughs) I pardon you. Later Goeth tries out the power of pardoning but then stands at the mirror fascinated with his emperor like power, imagining himself with the restrained imperial might, but the new image doesn't fit. He kills again with a rifle from the Villa; a pardon wasn't as powerful or pleasing as sporting target practice. 13 In one of the most powerful scenes in the movie that further establishes the personality of Goeth fitting into Meloy’s distinction of the violent destructive psychopath he comes to the basement to tell Helen. I came to tell you that you really are a wonderful cook and a well-trained servant. I mean it. If you need a reference after the war, I'd be happy to give you one. It's kind of lonely down here, it seems, with everyone upstairs having such a good time. Does it? You can answer. 'What was the right answer?' That's-that's what you're thinking. 'What does he want to hear?' The truth, Helen, is always the right answer. Yes, you're right. Sometimes we're both lonely. Yes, I mean, I would like, so much, to reach out and touch you in your loneliness. What would that be like, I wonder? I mean, what would be wrong with that? I realize that you're not a person in the strictest sense of the word. Maybe you're right about that too. You know, maybe what's wrong isn't - it's not us - it's this. I mean, when they compare you to vermin and to rodents and to lice, I just, uh...You make a good point, a very good point. (He strokes her hair) Is this the face of a rat? Are these the eyes of a rat? That's not a Jew's eyes. (He brings his hand over her breast) I feel for you, Helen. (He decides not to kiss her) No, I don't think so. You're a Jewish bitch. You nearly talked me into it, didn't you? As well the scene in which Goeth speaks out for Schindler after he is imprisoned for kissing a Jewish girl in public at a factory party, bonds them in identification as ironically Goeth probably saved Schindler’s life. Goeth makes distinctions between Schindler the lover of women and Goeth the killer of women 14 as Goeth arranges a bribe with an SS man for Schindler breaking the Race and Resettlement Act3. He likes women. He likes good-looking women. He sees a beautiful woman - he doesn't think. He has so many women. They love him, yeah, they love him. I mean, he's married, yeah, but... All right, she was Jewish, he shouldn't have done it, but you didn't see this girl. I saw this girl. This girl was, wuff, very good-looking. They cast a spell on you, you know, the Jews. When you work closely with them like I do, you see this. They have this power, it's like a virus. Some of my men are infected with this virus. They should be pitied, not punished. They should receive treatment, because this is as real as typhus. I see this all the time. It's a matter of money, hmm? This dialogue is meant to reveal not only Schindler’s erotic impulsive behavior but that Goeth unknowingly jealously identifies with Schindler’s success with women and simultaneously projects malevolent aspects into women leaving him impotent with fearful rage and violent to others. Three types of leaders If the reader accepts the idea that cinema construction reflects cultural concerns and values then this study of Schindler’s List offers a vehicle for examining a perspective on leadership in War in particular and leaders in general. The three types of leaders demarcated in this film are the manipulative but caring narcissist (Schindler), the destructive impotent narcissist (Goeth) and the work group leader (Stern). 3 Hitler authorized Himmler to establish a Race and Resettlement Office under the aegis of the SS. It was the Race and Resettlement Office that was to be responsible for the `racial' purification of the Reich and the establishment of a Nordic empire. 15 Into these iconic representations are embedded some important distinction not only among kinds of personality types but also kinds of leaders. I will address Stern first. Stern is portrayed as a kindly efficient man, working as Schindler’s subordinate to first help Schindler start his business, then to compile the original List of people who will first work in the factories and then survive while making sure the plant runs smoothly. Ultimately he becomes Schindler’s coach, counseling him how to keep the wheels of bought safety functioning and his adjunct in bribing ghetto officials to get certain workers in their factory, preparing the list of workers taken to Czechoslovakia and ultimately saved. He survives by working for Goeth as well. He is portrayed as a reluctant expediter whose inner life and affiliations are never revealed and in the nearly last scene blesses Schindler with a gold ring4. He is the leader as manager, the extension of the authority’s ego and wishes, and the man whose self-interests never appear while continuously maintaining a non threatening stance to his hierarchical superiors. He is necessary for success, possessed of many skills and ultimately a survivor. He appears altruistic without narcissistic self interests. North Americans seem concerned to integrate self esteem and altruistic goals (Staub, 2004) but these are not necessarily over-lapping interests in leaders. Altruistic values and behavior in individuals and leaders such as Stern and Schindler may serve complex interests. They may serve self interest motivated by real and anticipated rewards; they may serve moral interests guided by adherence to internal moral or political standards or they may serve altruistic goals motivated by a desire to help others, either to reduce their stress or pain or to compensate for guilt feelings. Schindler’s sensual self interest 4 The inscription on the ring made symbolically from a gold filling carries the quote from the bible'. Whoever saves one life, saves the world entire “ 16 is in food, drink and women. He is a man interested in his own pleasures and perhaps in ensuring his own survival and as portrayed as shameless in his narcissistic self interest. Ironically destructive individuals or leaders such as Goeth may similarly be motivated by self interest and moral or political internal standards. It would then seem that what distinguishes Schindler from Goeth in this film can be found in the altruistic realm of behavior. Repeatedly Schindler is seen performing acts of kindness, giving food to Stern, counseling and then saving Helen, cooling off a cattle car filled with people with water. Despite his self interest, and his personal appetites, he is capable of concern for others. Concern for others seems to have two specific roots as measured in social psychology: empathy and prosocial value orientation, that is a positive regard for other human beings and a feeling of personal responsibility for their welfare. It is not possible to psychoanalyze a cinematic representation; never the less psychoanalysis has something to offer in terms of understanding altruism in leaders that may confirm further distinctions between Schindler and Goeth. Goeth for many is the personification of Nazi evil. "Evil," as used here, means most simply a psychic absence of a capacity for concern and in its place is a fear of being overwhelmed by internal or external destructive forces. In his speech to Helen we see evidence of Goeth’s experience of Helen as destructive. In the final card game with Schindler we see his confusion about her fate.5 We may 5 Schindler proposes to put Helen's name in the last line left on the final page: "I'll never find a maid as welltrained as her in Berlin. They're all country girls." Goeth's conflicted affection for the girl, and his distrust of Schindler's consummate deal-making, sleight-of-hand talents, make it difficult for him to agree to a card game to decide Helen's fate: Schindler: She's just going to Auschwitz # 2 anyway. What difference does this make? Goeth: She's not going to Auschwitz. I'd never do that to 17 understand in this the psychic effort to rid himself of certain undesirable aspects of its own being by dissociating itself from its unwanted elements and attempting to evacuate them through projection into the being and self-experience of another. The effect of this malignant projection is always destructive to another because it operates to degrade the being of the other by filling it with unwanted dangerous or self-destructive attributes. From another vantage the destructive person in power gives in and sides with internal demonic promptings because it can not assume an internal position of concern. Without psychic support, Goeth cannot maintain his integrity when erotically aroused or invested with concern. From the dialogue we can see how Goeth makes use of mechanisms of extreme objectification of the other as a special category “not human “by use of powerful defenses of denial, splitting, dissociation, externalization, and projective identification. Re reading the dialogue between Goeth and Helen we can witness Goeth’s transformation from libidinal interest to malignant projection to a vulnerable paranoid position of seeing the other as a viral infection. He can not resist the appeal of the destructive in the preamble to the final card game with Schindler, to make death. Summary her. No, I want her to come back to Vienna with me. I want her to come work for me there. I want to grow old with her. Schindler: Are you mad? Amon, you can't take her to Vienna with you. Goeth: No, of course I can't. That's what I'd like to do. What I can do, if I'm any sort of a man, is the next most merciful thing. I should take her into the woods and shoot her painlessly in the back of the head. (Goeth reconsiders the wager) What is it you said for a natural twenty-one? Fourteen thousand, eight hundred? 18 In summary, I have attempted to convey in words, exactly what Spielberg visually and perhaps unintentionally created in his movie: the tension filled relationship between three different types of leaders. While Spielberg used all of the devices of the visual media, images without sound, red children’s coat in a black and white film, juxtaposition of contrasting scenes, close-up of faces, foregrounded action, I have tried to convey in words something about the psychology of leaders that organizes and deepens the perception of the film. The film is a cinematic landscape of a familiar war infected group terrain in which are juxtaposed moments of affiliative caring and the absolute power to destroy life and meaning. As even the image, behavior and fate of Amon Goeth symbolizes the old (Nazi) fascistic leader in cinematic reality brilliantly juxtaposed to both the flawed character of the business man Schindler, who became a “ righteous person “, and Stern “the silent effective minister “ there is even more to the images than a discourse of a leaders power or situational violence. There is the contrast between the forces creating and enjoying destruction and those that exhibit concern. These are still contemporary political concerns. For those interested in the distinction between the fantasy of the movie and the reality of Schindler and Stern I have included the review of the latest book on Schindler in the appendix. Films Hotel Rwanda Directed and produced by: Terry George Released By: MGM/UA Released12/22/2004 19 The Pianist Directed by Roman Polanski Producer Alain Sarde Released by Focus released 2002 Private Ryan Directed and Produced by Steven Speilberg Released by Paramount 1998 Platoon Directed by Oliver Stone produced by John Daly Realeased by Orion Pictures released 1986 Schindler’s List Directed by Steven Spielberg Producer Gerald Molen Released By: Universal released 1994 Bion, W. R. (1970). Attention and Interpretation. New York: Jason Aronson. Crowe, D. M. (2004). The True Story of Oskar Schindler. Boulder Colorado: Westview Press. Douglas, M. (1995). Mind Hunter: Inside the FBI's serial Killer unit: Pocket Books. Freud, S. (1921). Group Psychology and the Analysis of the Ego. In S. E. 1955 (Ed.) (Vol. 18). London: Hogarth Press. Gourevitch, P. (1994). A Dissent on"Schindler's List". Commentary, Vol 97, 4952. 20 Insdorf, A. s. (1989). Indelible Shadows : Film and the Holocaust (Second Edition ed.). Cambridge Mass: Cambridge University Press. Keneally, T. (1993). Schindler's List. New York: Simon Schuster. Meloy, J. R. (1988). The Psychopathic Mind: Origins, Dynamics and Treatment. New York: J Arronson. Newsinger, J. (1993). Do you walk the Walk; Aspects of Masculinity in some Viet Nam War Films. . In Kirkham. P. and. Tumin. P. (Ed.), In, You Tarzan : Masculinity, Movies and Men (pp. 126-137).). New York: St Martin's Press. Roth, S. (1993). The Shadow of the Holocaust. In R. Moses (Ed.), Persistent Shadow of the Holocaust (pp. pp. 37-63). Madison Ct: International Universities Press.. Staub, E. (2004). Basic Human Needs: Altruism and Aggression. In A. Miller (Ed.), The Social Psychology of Good and Evil (pp. 51-84). New York: The Guilford Press. Weisel, E. (1960). Night . New York: Hill and Wang Appendix Schindler, a man with many flaws, risked his life and his fortune to save more Jews during the Holocaust than anyone else did. While the young Swedish diplomat Raoul Wallenberg saved a larger number of Jews, he had the assistance of an entire team of people and the financial support of American Jews. In contrast, Schindler had only the assistance of his wife, Emilie. 21 Moreover, Schindler performed his heroic deeds only a short distance from Auschwitz. Schindler's road to rescuing almost 1,100 people was hardly predictable. Born in the Sudetenland, the area of Czechoslovakia that was home to a large German population and on which Hitler had designs, Schindler spied for the Abwehr, the German army's espionage unit. He helped pave the way for Germany's 1939 dismemberment of Czechoslovakia. Shortly after Germany invaded Poland, Schindler showed up in Krakow with one intention: to make money. He bought a Jewish-owned factory for a small fraction of its original worth and then contracted with the SS for Jewish workers. A lackluster businessman, Schindler let knowledgeable Jews run the factory while he wined, dined and bribed German officials. As the Germans moved to murder, Schindler -- revolted by this development -- was transformed from self-interested shady, entrepreneur to fierce defender of his workers. Schindler, the former German spy, became a courier for Jewish aid organizations. He helped these organizations supply Jews with money, food and medicine, and transmitted important information about the gassings in Auschwitz. In contrast to the impression given by Steven Spielberg in "Schindler's List," the famous list was not compiled by Schindler but by one of his Jewish administrators, Marcel Goldberg. Jews bribed Goldberg to get themselves on it as inclusion on the list could mean the difference between life and death Schindler did not create the list, but, motivated by a deep sense of compassion for these people and revulsion at the Germans' actions, he did feel responsible for keeping these people alive, particularly during the harrowing final 22 months of the war. As the situation in Krakow deteriorated, he moved his factory to Czechoslovakia. By so doing, he saved the lives of his 1,100 workers. Schindler's saga did not end with Germany's defeat. After the Holocaust, Yad Vashem initially refused to honor him as a Righteous Gentile. How, it wondered, could it balance his membership in the Nazi Party with his efforts to save Jews? Those Jews whose factory he had expropriated protested to Yad Vashem that he acquired the considerable sums he spent to save his workers through the Aryanization of Jewish property and the use of slave labor. They tried to take legal action against him. Other Schindler Jews objected vehemently, arguing that, but for his actions, they would not have survived. Reviewed by Deborah E. Lipstadt Copyright 2005, The Washington Post Co.