The Gospel of Luke - Archdiocese of Galveston

advertisement

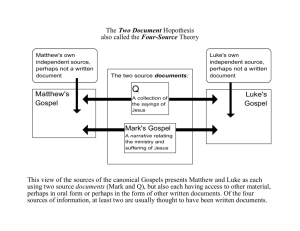

1 Archdiocese of Galveston-Houston Gift of the Gospels Commentary on the Gospel of Luke Lesson 1: Overview The New Testament: A Library of Books Whenever we purchase a new book we look at the table of contents. In the case of the New Testament, the table of contents consists of 27 books, written by different authors at different times to address different audiences. Thus the New Testament is not a book but rather a library of books. These books were written in koine Greek, the vernacular Greek of the first century. They constitute the canon of the New Testament, that is, they are seen as authoritative by Christians for religious belief. The Canon of Sacred Scripture The English term “canon” comes from a Greek word that originally meant “ruler” or “measuring rod.” A canon was used to make straight lines or to measure distances. When applied to a group of books, it refers to a recognized list (body) of literature. With reference to the Bible, the term canon denotes the collection of books that are accepted as authoritative by a religious body, the church. Thus, for example, we can speak of the canon of the Old Testament or the canon of the New Testament. The Layout of the New Testament Gospels: The Beginning of Christianity Matthew Mark Luke John Acts: The Spread of Christianity Acts of the Apostles Epistles: Letters Addressed to Early Christian Communities Pauline Epistles Romans 1 and 2 Corinthians Galatians Ephesians Philippians Colossians 1 and 2 Thessalonians 1 and 2 Timothy Titus Philemon General Epistles Hebrews James 1, and 2 Peter 1, 2, and 3 John Jude Apocalypse: Literature to Inspire Hope to Christians during Times of Persecution Book of Revelation Copyright 2010 Archdiocese of Galveston-Houston 2 The Gospels: “Written So That You May Come to Believe” (John 20:31) The Gospels have as their purpose to evoke faith. They are based on reliable testimony and eyewitness accounts of the life of Jesus (see John 21:24). They do not always provide detailed and exact historical information but, rather, they present revelations about Jesus and his followers that are directed at inspiring readers to appropriate such a lifestyle. The Gospels are faith literature, which were written by people of faith to inspire faith. They are not video camera recordings or DVD’s of events; rather they are proclamations of belief. They were written to inspire peoples’ belief, not to simply report information, or as the Gospel of John states so well: “But these are written so that you may come to believe that Jesus is the Messiah, the Son of God, and that through believing you may have life in his name.” (John 20:31). Stages of Gospel Development The Gospels went through three stages of development, as outlined by the Roman Pontifical Biblical Commission in its “Instruction on the Historical Truth of the Gospels.” In this document, biblical scholars of the Catholic Church present the first stage of Gospel development as: PUBLIC MINISTRY OR ACTIVITY OF JESUS OF NAZARETH (the first third of the first century). Jesus did things of note, such as heal people, perform miracles, preach and teach. He orally proclaimed his message, and interacted with others, namely John the Baptist, Jewish religious figures, and his disciples. The interpreted memories of Jesus’ words and deeds are what the Gospels record. These memories were selective and do not include such trivia as Jesus’ weight and height, the color of his eyes and hair. The second stage of Gospel development is: (APOSTOLIC) PREACHING ABOUT JESUS (the second third of the first century). Those who had seen and heard Jesus had their choice to follow him confirmed through post-resurrection appearances; and they came to full faith in the risen Jesus as the one through whom God was manifested. That post-resurrection faith illumined the memories of what they had seen and heard during the pre-resurrection period; and so they proclaimed his words and deeds with enriched significance. These preachers are referred to as apostolic because they understood themselves as being sent forth (Greek: apostallein) by the risen Jesus, and their preaching is often described as kerygmatic proclamation intended to bring others to faith. Another factor operative in this stage of Gospel development was the necessary adaptation of the preaching to a new audience. While Jesus was a Galilean Jew of the first third of the first century who spoke Aramaic, by mid-century his Gospel was being preached in Greek throughout the Diaspora (Jews living outside of Palestine) to urban Jews and Gentiles. This change of language involved translation in the broadest sense of that term. It required a rephrasing in vocabulary and patterns that would make the message intelligible and alive for new audiences. The final stage of Gospel development is: THE WRITTEN GOSPELS (the last third of the first century). During this stage, oral traditions and preachings were collated together into a written form. The era from 65100 A. D. is when all four canonical Gospels were written. It was the stage of articulation. As for the evangelists or Gospel writers/authors, according to traditions stemming from the second century and reflected in titles prefaced to the manuscripts of Gospels circa 200 A.D. (or even earlier), the Gospels were attributed to apostles. (For a more detailed explanation of the three stages of formation of the Gospels, see The Catechism of the Catholic Church, # 126). This recognition — that the evangelists were dependent on eyewitnesses of Jesus’ ministry — is important for understanding the differences among the Gospels. Eyewitnesses remember things differently. For example, John (chapter 2) reports the cleansing of the Temple at the beginning of Jesus’ ministry and Matthew (chapter 21) reports the cleansing of the Temple at the end of the ministry. Copyright 2010 Archdiocese of Galveston-Houston 3 In sum, the Gospels are “Good News,” i.e., information that is inspiring in order “…that you may know the truth concerning the things of which you have been informed” (Luke 1:4). Matthew, Mark and Luke Matthew, Mark, and Luke are often called the “Synoptic Gospels.” This is because they have so many stories in common that they can be placed side by side in columns and “seen together” (the literal meaning of the word “synoptic”). Indeed, not only do these Gospels tell many of the same stories, they often do so using the very same words. This phenomenon is virtually inexplicable, unless the stories are derived from a common literary source. Consider a modern day parallel. You may have noticed that when newspapers, magazines, and books all describe the same event, they do so differently. Take any three of today’s newspapers and compare their treatment of the same news item. At no point will they contain entire paragraphs that are word for word the same, unless they happen to be quoting from the same source, for example, an interview or a speech. These differences occur because every journalist wants to emphasize certain things and has his or her own way of writing. When you find that two newspapers have exactly the same account, you know that they have simply reproduced a feature from somewhere else. This happens, for example, when two newspapers pick up the same news story from the Associated Press. We have a similar situation with the Gospels. There are passages shared by Matthew, Mark, and Luke that are verbatim (see Matthew 13:1-9; Mark 4:1-9; Luke 8:4-8). This can be scarcely explained unless all three of them drew these accounts from a common source. But what was it? The question is complicated by the fact that the synoptics not only agree extensively with one another, they also disagree. There are some stories found in all three Gospels, others found in only two of the three (see Matthew 3:7-10; Luke 3:7-9), and yet others found only in one (see Luke 3:10-14). Moreover, when all three Gospels share the same story, they sometimes give it in precisely the same wording and sometimes word it differently. Or sometimes two of them will word it the same way and the third will word it differently. The problem of how to explain the wide-ranging agreements and disagreements among these three Gospels is called the “Synoptic Problem.” “Synoptic Problem” Biblical scholars have offered a number of theories over the years to solve the Synoptic Problem. We will focus on the one that most scholars have come to accept as the least problematic. This explanation is sometimes referred to as “four-source hypothesis.” According to this hypothesis, Mark was the first Gospel to be written. It was used by both Matthew and Luke. In addition, both Matthew and Luke had access to another “source,” Q (from the German word for “source,” quelle). Q provided Matthew and Luke with the stories that they have in common that are not, however, found in Mark. Moreover, Matthew had a source (or group of sources) of his own, from which he drew stories found in neither of the other Gospels. Scholars have simply labeled this source(s) “M” (for Matthew’s special source). Likewise, Luke had a source(s) for stories that he alone tells; this is called “L” (for Luke’s special source). Hence, according to this hypothesis, four sources lie behind our three Synoptic Gospels: Mark, Q, M, and L. No written copies of Q, M, and L exist. To help prepare for our study of the Gospels, the following timeline is presented: Timeline 30-100 A.D. Oral and Written Tradition about Jesus ___________________________________________________________________ 4 B.C.E.—30 A.D.50-60 Life of Jesus Letters of Paul 65-70 80-85 95-100 Mark Luke, Matthew John Copyright 2010 Archdiocese of Galveston-Houston 4 Before reading any of the four Gospels it will be helpful to have some information about the various Jewish religious sects that existed at both the time of Jesus and the writing of the Gospels. Jewish Groups and the Gospels Jewish Scribes in the first century represented the literate elite, those who could read and study the sacred traditions of Israel and, presumably, teach them to others. Recall that most Jews, as well as most other people in the ancient world, were not highly educated by our standards; those who were educated enjoyed a special place of prominence. Pharisees, were Jews who were reformers strongly committed to maintaining the purity laws set forth in the Torah and who developed their own set of more carefully nuanced laws to help them do so. They appear as the chief culprits in the Jewish opposition to Jesus during much of his ministry in Mark’s Gospel, as well as the other Gospels. Herodians were a group of Jews whom Mark mentions but does not identify (3:6; 12:13; see also Matt. 22:16). They are described in no other ancient source. Mark may understand them to be collaborationists, that are supporters of the Herods, the rulers intermittently appointed over Jews in Palestine by the Romans. Sadducees were Jews of the upper classes who were closely connected with and strong advocates of the Temple cult in Jerusalem. They were largely in charge of the Jewish Sanhedrin, the council of Jews that advised the high priest concerning policy and served as a kind of liaison with the Roman authorities. Zealots were a group of Jews characterized by their insistence on violent opposition to the Roman domination of the Promised Land. A group that had been centered in Galilee fled to Jerusalem during the uprising against Rome in 66-70 C.E.; they overthrew the reigning aristocracy in the city and urged violent resistance to the bitter end. Essenes A group of Jews whose name may come from an Aramaic word meaning “pious,” withdrew from Jerusalem and active participation in the Jerusalem Temple. They settled in the Judean wilderness in isolated monastic communities where they studied the Scriptures and developed their rule of life. Essenes were known for their piety such as daily prayer, prayer before and after meals, strict observance of the Sabbath, daily ritual bathing, emphasis on chastity and celibacy, wearing white robes as a symbol of purity, communal meals, and sharing all property in common. Chief Priests were the upper classes of the Jewish priesthood who operated the Temple and oversaw its sacrifices. They would have been closely connected with the Sadducees and would have been the real power players in Jesus’ day, the ones with the ear of the Roman governor in Jerusalem and the ones responsible for regulating the lives of the Jewish people in Judea. Their leader, the high priest, was the ultimate authority over civil and religious affairs when there was no king in Judea. Copyright 2010 Archdiocese of Galveston-Houston 5 The Gospel of Luke The Gospel of Luke is part of a two-volume set; the other is Acts of the Apostles. Both volumes were composed by the same author. They were intended to be read in sequence. Luke presents the good news of Jesus, the Gospel; and Acts of the Apostles presents the good news of the Church and what people did in response to that Gospel. In the Gospel of Luke, Jesus moves from Galilee to Jerusalem, toward the center of the Jewish world. In Acts of the Apostles, the “way” — a synonym for the followers of Jesus — moves from Jerusalem to Rome, the center of the Greco-Roman world. Outline of the Gospel of Luke I. II. III. IV. V. VI. VII. Luke 1:1-4: the Prologue Luke 1:5-2:52: The Infancy Narrative Luke 3:1-4:13: Preparation for the Ministry of Jesus Luke 4:14-9:50 The Ministry of Jesus in Galilee Luke 9:51-19:27: The Journey to Jerusalem Luke 19:28-21:38: Jesus’ Ministry in Jerusalem Luke 22:1-24:53: The Passion and Resurrection Narratives Luke the Evangelist Not much is known about the evangelist Luke. Church tradition says that he was both a physician and an artist from Syria who completed his gospel between A.D. 80 and 90.There are three brief references to “Luke” in the New Testament. Philemon mentions a “Luke” as Paul’s fellow worker (verse 24); and 2 Timothy 4:11 notes that a “Luke” was alone in staying with Paul in the days of Paul’s imprisonment. Finally, Colossians 4:10-14 mentions a “Luke,” a physician and Gentile. Are these references to Luke the evangelist? It is unclear! Who was this highly gifted and reflective evangelist? The only thing that can be said with certainty is that Luke was a second generation Gentile Christian. No ancient tradition suggests a place of composition for the gospel. Scholarly consensus holds that the Gospel was composed in Antioch. Luke’s gospel comes from the middle period of gospel writing (83-90 C.E.); it was written after Mark (on which it depends) and before John. Luke’s Writing Style Luke is an economical writer who avoids repetitions and superfluous information. His use of Greek is among the finest in the New Testament, and he is well versed in Greco-Roman literary style. Luke uses polished prose, tells a story well and always takes his audience into consideration when he writes. Luke writes with an eye toward influencing Rome positively toward Christianity. The primary audiences for Luke’s writing were Gentiles, some of whom were Roman citizens. For these people, a literary approach that would not jar educated tastes was required. And so, using the Septuagint (the Greek translation of the Old Testament) as his stylistic model, Luke writes in the mode of a Roman historian, using literary forms and designs drawn from that world. Luke is a classic defender of the faith. To counter the Romans who viewed Christianity as having sordid origins since it sprang from the Jews who the Romans considered suspect, Luke demonstrates Christianity’s universality. The salvation offered by Jesus is available to everyone, not just Jews: “…and all flesh shall see the salvation of God” (Luke 3:6). Dedicated to a Gentile, the Theophilus of Luke’s prologue (1:1-4; see Acts of the Apostles 1:1-5) the two-volume set commends Christianity to a Gentile world; Luke argues that Church and state can live peaceably together. His writings were not only a defense to the Empire, but a tool for its evangelization. Copyright 2010 Archdiocese of Galveston-Houston 6 Further, since theophilus means “God lover” some scholars suggest that Luke is writing to all God lovers not just a particular historical person. Characteristics and Themes in Luke’s Gospel Pairing Men and Women A technique used by the writer of the Gospel of Luke is the pairing of men and women. He pairs the birth announcement to Zechariah (1:5-20) about the birth of John the Baptist with the birth announcement to Mary (1:26-38) regarding the birth of Jesus. In the presentation of Jesus in the Temple, both the man Simeon and the woman Anna receive the infant Jesus (2:25-38). Jesus cures both the male demoniac and Peter’s mother-in-law (4:33-39) as well as the male centurions’ slave (7:1-10) and the raising of the dead son of a widow (7:11-5). The Gospel of Luke and Women In Luke’s gospel, women have a prominent role, one that at times puts them on a par with men. There are ten named and unnamed women in Luke’s gospel. In Jesus’ teaching in Luke, women are mentioned 18 times; speak 15 times; and in 10 of these instances their words are given. In Luke, there are women disciples who provide for Jesus and his disciples out of their financial means (Luke 8:1-3). Two of Jesus’ closest friends are Martha and Mary of Bethany (Luke 10:38-42). Further, women follow Jesus to Calvary (23:27-31), are present at the crucifixion (23:49; see 23:55-56), and discover the empty tomb after Jesus’ resurrection (24:1-12). The Gospel of Luke and the Holy Spirit In Luke’s gospel, the role of the Holy Spirit is underlined. Often known as the Gospel of the Holy Spirit, Luke provides more references to the Holy Spirit than any other of the Synoptic Gospels (see Luke 1:15, 35, 41, 67; 2:26-27; 3:16; 3:21-22; 4:1-14; 4:18-19; 12:12). As a matter of fact, the expression “Holy Spirit” appears 13 times in the Gospel of Luke and 41 times in Acts of the Apostles, which was composed by the same author. From the very beginning of the Gospel of Luke, the Holy Spirit plays a key role. Zechariah is told that his son, John the Baptizer, will “even before his birth be filled with the Holy Spirit” (Luke 1:15). Jesus’ very origin is said to be from the Holy Spirit, for the angel says to Mary: “The Holy Spirit will come upon you and the power of the Most High will overshadow you . . .” (Luke 1:35). When Mary visits Elizabeth, the Gospel of Luke points out that “. . . Elizabeth was filled with the Holy Spirit” (Luke 1:41). Why? Because Mary, who is the pregnant one bearing Jesus, transfers to John and his mother Elizabeth God’s Spirit. Even unborn, Jesus is a bearer of the Spirit to all whom he encounters. Once Zechariah, the father of John the Baptizer, is able to speak, he proclaims a canticle about the meaning of his son’s birth and Luke is quick to point out that John’s “. . . father, Zechariah, was filled with the Holy Spirit” (Luke 1:67) as he began to proclaim “Blessed be the Lord God of Israel.” In the story of the presentation of Jesus in the temple — which is found only in the Gospel of Luke — the aged Simeon is said to have had the Holy Spirit rest on him and promise him that he would not see death before he saw the messiah (Luke 2:25-27). Jesus is preeminently the man of the Holy Spirit, and the giver of the Spirit in the Gospel of Luke. John the Baptizer identifies Jesus’ role as being the living conduit of the Spirit. John says: “I baptize you with water; but one who is more powerful than I is coming; . . . He will baptize you with the Holy Spirit and fire” (Luke 3:16). A pivotal point in Jesus’ life, as portrayed in the Gospel of Luke, is his baptism (Luke 3:21-22). When Jesus is baptized, we see clearly that the Holy Spirit is being poured out upon him. And the Spirit appears in the form of a dove. Why a dove? The dove is the sign of a new season in the Song of Songs Copyright 2010 Archdiocese of Galveston-Houston 7 (2:12), and the herald of the new world after the flood (Genesis 8:8-12); and its presence at the baptism of Jesus suggests the opening of a new age. For Luke, Jesus’ baptism is God’s decisive intervention in our history. Here at the Jordan River, Jesus saw and experienced in a most vivid and human way the descent of the Holy Spirit upon him, and it is under the auspices of the Spirit that Jesus’ ministry begins. In the power of the Spirit, Jesus was driven into the wilderness (desert) (Luke 4:1); in the power of the Spirit he returned to Galilee (Luke 4:14). Further, Luke is quite clear that Jesus brought the Spirit of God. In fact, when Jesus begins his public ministry he stands up in the synagogue in Nazareth and applies to himself the words of the prophet Isaiah: “The Spirit of the Lord is upon me, because he has anointed me to bring good news to the poor. He has sent me to proclaim release to the captives and recovery of sight to the blind, to let the oppressed go free, to proclaim the year of the Lord’s favor” (Luke 4:18-19). Luke sees Jesus as a vehicle of the Spirit and the instrument of a new prophetic outpouring. The Gospel of Luke and the Themes of Poverty, Mercy and Forgiveness Luke’s gospel is also known as the Gospel of the poor, and the Gospel of mercy and the forgiveness of God. Luke sees Jesus as friend and advocate of those whom society ignores or turns from in distaste, the poor, handicapped persons, public sinners, and all who found themselves on the fringes of the community. The Lucan Jesus has great compassion for all of these. In Luke’s day, none bore the brunt of ostracism more than the Samaritans. Only Luke tells the story of the Good Samaritan (Luke 10:30-37), and in the story of the cleansing of the ten lepers by Jesus, the only leper to return with gratitude to thank Jesus is a Samaritan (see Luke 17:11-19). The most famous of Jesus’ parables on forgiveness — the parable of the prodigal son (Luke 15:11-32) — is found only in Luke. The Gospel of Luke and Prayer Luke’s gospel stresses prayer. Jesus is portrayed in Luke as praying “without ceasing.” Jesus prays often in the Gospel of Luke (see 3:21; 5:16; 6:12; 9:18; 9:28-29; 11:1; 22:40-46). In Luke, Jesus prays at every major decision-making moment in his life. Luke provides this as a model for all who would be followers of Jesus. In addition, in the Gospel of Luke Jesus tells three parables about prayer The Gospel of Luke and Parables Luke’s gospel contains the largest number of parables, the two most famous being the parable of the Good Samaritan (Luke 10:29-37) and the Prodigal Son (Luke 15:11-32). Luke’s gospel alone contains three parables about poverty and riches: the rich fool (Luke 12:13-21), the shrewd manager (Luke 16:1-13), and the rich man and Lazarus (Luke 16:19-31). Luke records three parables on prayer: the friend at midnight (Luke 11:5-8), the parable of the persistent widow (Luke 18:1-8), and the parable of the Pharisee and the tax collector (Luke 18:9-14). Further, Luke provides parables on being a disciple: the parable of the two builders (Luke 6:47-49), the tower builder and the warring king (Luke 14:28-33), and the parable of the unworthy servant (Luke 17:7-10). The Gospel of Luke and Jesus’ Table Fellowship Luke is also known as the Gospel of table fellowship. There are ten meal stories in Luke. They include: a meal at the house of Levi (5:27-39), at the home of Simon the Pharisee (7:36-50), breaking bread in Bethsaida (9:10-17), dining at the home of Martha (10:38-42), at the home of a Pharisee (11:37-54), a Sabbath meal with a leading Pharisee (14:1-24), a meal at the house of Zacchaeus (19:1-10), Jesus’ celebrating of the Passover meal with his disciples (22:14-38), the risen Jesus breaking bread with the disciples on the road to Emmaus (24:13-35) and with his disciples in Jerusalem (24:36-53). Often, when Jesus dines in the Gospel of Luke, an outcast or socially unacceptable person becomes included in Jesus’ table fellowship. Copyright 2010 Archdiocese of Galveston-Houston 8 Luke: The Gospel of Joy Finally there is the theme of joy. The word “joy” appears more often in the third Gospel than in any other New Testament work. In the theological world view of the Gospel of Luke we live in a world redeemed and transformed by the birth, life, ministry, passion and death of Jesus Christ. In such a world there can be no other Christian response than joy. The Prologue of the Gospel of Luke Read Luke 1:1-4 The Gospel opens with a single sentence typical of ancient literature. A Gentile audience would expect such a prologue, and Luke is simply supplying it. He addresses it to a person named Theophilus whose identity is unknown. The guesses as to his identity include the possibility that he was a benefactor, a Church leader or even a civil authority. On the one hand, it seems most likely that Theophilus represents an audience of believers of Gentile origin whose adherence to Christianity Luke wishes to confirm by communicating a new sense of their identity precisely as Gentile members of the People of God. On the other hand, using the name Theophilus (literally, “Beloved of God”) universalizes the identity allowing every reader to be the Gospel’s addressee. The prologue also tells us a great deal about Luke and his understanding of himself and about the methods and aims of his writing. First, he locates himself in the sweep of the tradition. At the beginning stand those who were “eyewitnesses and ministers of the word” (verse 2). The reference is presumably to the original disciples (notably the apostles), who after Pentecost were empowered by the Spirit to proclaim what they had seen and experienced. Later there were others who “set their hands” to composing the narratives of the “events that have been fulfilled among us.” Secondly, Luke’s aim is to write ---in contrast it would seem, to his predecessors---an “orderly account,” designed to produce in the reader “firm assurance” in regard to things in which he has been instructed. The term “orderly” as used here does not necessarily mean an account that narrates things in strict chronological order. The sense is rather that of setting the various episodes pertaining to Jesus so as to demonstrate the truth and inner meaning of the whole story. Third and finally, for Luke, the purpose of all of this is to provide assurance to his Gentile audience who had never experienced the historical Jesus that their choice to become disciples of Jesus is a valid one. Review and Discussion Questions How do you react to the stages of development that the Gospels went through? What do we know about the author of the Gospel of Luke? With which themes in the Gospel of Luke can you readily identify? Copyright 2010 Archdiocese of Galveston-Houston