14chapter 14

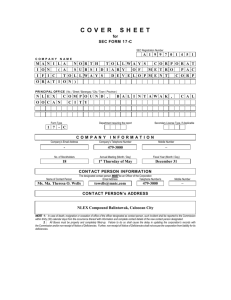

advertisement