ACTION POUR LES ENFANTS

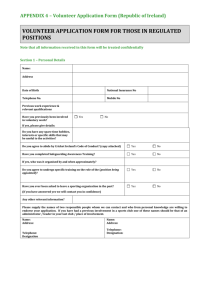

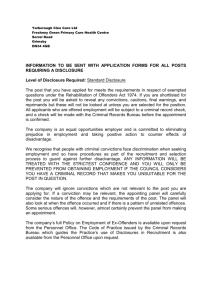

advertisement