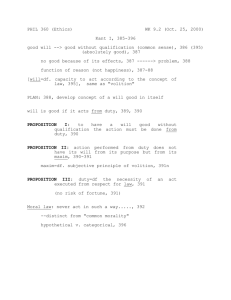

Affirmative Duty after Tarasoff

advertisement