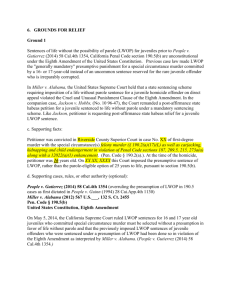

life without parole as a conflicted punishment

advertisement