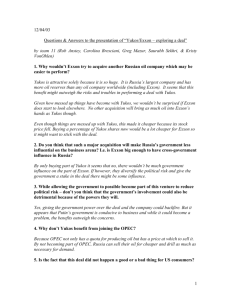

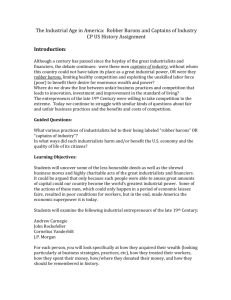

Standard Oil and Yukos in the Context of Early Capitalism in the

advertisement