Written Materials

advertisement

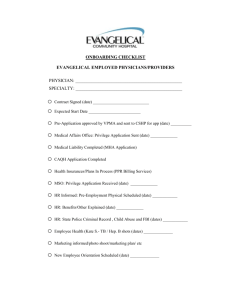

Don’t Stumble Coming Out of the Gate – Issues to Address When Acquiring a Physician Practice Carol W. Carden, CPA/ABV, ASA, CFE Pershing Yoakley & Associates, P.C. Charlene L. McGinty, Esq. Kim S. Ruark, Esq. McKenna Long & Aldridge, LLP Introduction Given the significant changes in the health care system and the delivery of care, hospital-physician alignment and integration have been growing exponentially in the past several years. In particular, hospital acquisitions of physician practices and subsequent employment of physicians by the hospital increased following passage of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act in 2010 (the “ACA”).1 For instance, the 2012 AMA Physician Practice Benchmark Survey showed that 23% of physicians were employed by hospitals in 2012 compared to 16.3% as recently as 2007-2008.2 In a 2012-13 survey of hospital executives, more than half indicated they were actively involved in physician practice acquisitions.3 Although the pace of acquisitions appears to have tapered slightly in recent months, hospitals and physicians continue to explore options and some level of practice acquisition will likely continue in the near term. Hospitals and physicians have numerous options for aligning their interests – medical director agreements, professional service arrangements, management agreements, sale of certain service lines and various others. For purposes of this paper, we have focused on a physician-hospital alignment model that includes a full practice acquisition by the hospital and contemporaneous physician employment by the hospital. While the actual process of acquiring a practice and employing physicians can seem simple, there are a number of factors to consider when structuring the arrangement. For instance, will the hospital employ physicians directly or establish a subsidiary (or multiple subsidiaries) to do so? Will ancillary services remain as a physician service or will they become hospital-based? Which types of practices fit with the hospital’s strategic planning? Where are they located? Has the 1 Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010, Pub. L. No. 111-148, 111th Cong. (2010) (as amended by the Health Care and Education Affordability and Reconciliation Act of 2010, Pub. L. 111-152, 111th Cong. (2010)). 2 2012 Physician Benchmark Survey, available online at http://www.ama-assn.org/resources/doc/healthpolicy/prp-physician-practice-arrangements.pdf. 3 Trend Watch: Physician Practice Acquisitions, Jackson Healthcare, available online at http://www.jacksonhealthcare.com/media-room/surveys/trend-watch-physician-practice-acquisitions-20122013.aspx. 1 ATLANTA 5549886.1 hospital thought through all steps necessary to bring in the new group(s)? A little advance planning and some time spent developing a strategy for practice acquisition can pay off in the long term and (hopefully) help ease the transition for all parties. If there is a referral relationship (past, current or potential) between the hospital, the physician group and/or its physicians, there are a number of legal and valuation issues to be considered in connection therewith, but the main concerns lie in compliance with the fair market value and commercial reasonableness requirements (as applicable) of the Stark Law (as defined below), the AKS (as defined below) and tax law considerations (regarding taxexempt hospitals, as applicable, reasonable compensation, and fair market value for services and/or leases). Self-referral laws and fraud and abuse laws at the state level can also be implicated and must be reviewed and addressed, but this paper discusses the federal law overlay for this physician-hospital alignment model. 1. The Employment Options a. In some states, the prohibition on the corporate practice of medicine or strong prohibitions on fee splitting may limit a hospital’s ability to employ (either directly or indirectly) physicians. In such states, a hospital may have to use a “friendly PC” or foundation model rather than employing physicians directly or through a hospital-owned subsidiary. State law in these jurisdictions will be the primary driver of the structure of this model, with the overlay of the federal law. b. In jurisdictions with no corporate practice prohibition, physicians may be employed directly by a hospital or by a wholly-owned subsidiary (or subsidiaries) of a hospital. In those jurisdictions where there is limited or no enforcement of this prohibition, the hospital may determine that there is an acceptable level of business risk in directly employing the physicians. If the physicians are employed by subsidiaries, it may give the hospital a mechanism to provide some autonomy to various practice groups that are acquired.4 Additionally, as discussed below, employment by a subsidiary that is structured as a “group practice” under the Stark Law (discussed below) may provide some flexibility for compensation models. c. Typically, the physicians are compensated on a productivity model based on a fair market value rate per wRVU for services that are personally performed by the physician. There may be some amount of guaranteed salary, along with productivity and quality bonus opportunities, as well as certain other payments for administrative research services and supervision of mid-level practitioners. 4 While a hospital may set up separate subsidiaries to house various physician practices (for instance, through single member limited liability companies), establishing numerous subsidiary physician practices can be cumbersome to manage and the implications of such a decision should be fully reviewed by hospital counsel and management. 2 ATLANTA 5549886.1 d. Ethics in Patient Referrals Act (the “Stark Law”)5 The Stark Law and its implementing regulations generally prohibit referrals by physicians to facilities and other providers for certain designated health services6 (“DHS”) that are reimbursable by Medicare7 if the referring physician (or a member of his/her immediate family) has a financial relationship with the entity providing DHS. Designated health services include inpatient and outpatient hospital services, as well as occupational therapy, physical therapy, clinical laboratory services, radiology services and radiation therapy, among other services. Financial relationships are broadly defined under the Stark Law and include both direct and indirect compensation arrangements, as well as ownership/investment interests. Otherwise prohibited referrals are permitted if the financial relationship between the parties fits within an appropriate exception to the Stark Law and regulations. It is important to note that the Stark Law is a strict liability statute – any financial arrangement that does not fit within an exception creates prohibited referrals. i. Bona Fide Employment Exception. For hospitals that directly employ physicians, the compensation arrangement must comply with the bona fide employment exception.8 Hospitals are permitted to pay employed physicians for identifiable services if the compensation paid is fair market value, not determined in a manner that takes into account the volume or value of referrals for DHS and commercially reasonable even if there were no referrals. This exception also permits payment of productivity bonuses based on the services personally performed by the referring physician. (A) A 2013 order in the Halifax9 case clarifies how a productivity bonus may be structured. In that case, the hospital established a bonus pool consisting of a percentage of the operating margin of its medical oncology services; and a group of medical 5 42 U.S.C. § 1395nn. 6 Designated health services generally include inpatient and outpatient hospital services, clinical lab services, radiology, radiation therapy, physical therapy, occupational therapy, speech therapy, outpatient prescription drugs, durable medical equipment, parenteral and enteral nutrients, prosthetics/orthotics and home health services payable by Medicare. 42 C.F.R. § 411.351. 7 But the United States Department of Justice and relators in False Claims Act cases are now arguing that the Stark Law also applies to submission of Medicaid claims for purposes of enforcement of the Stark Law through False Claims Act cases. Note that in the Halifax case (discussed below), the court refused to grant Halifax’s summary judgment motion to dismiss the Medicaid claims and held that the allegation that Halifax caused the Medicaid claims to be submitted by the Florida Medicaid agency was sufficient to state a FCA claim and, therefore, survive summary judgment. United States ex rel. Baklid-Kunz v. Halifax Hospital Medical Center et al., Order, 2012 WL 921147, 1, 4 (M.D. Fla. March 29, 2012). 8 42 U.S.C. § 1395nn(e)(2); 42 C.F.R § 411.357(c). 9 United States ex rel. Baklid-Kunz v. Halifax Hospital Medical Center et al., Case No. 6:09-cv-Orl-31TBS, M.D. Fla. (Nov. 13, 2013). The hospital settled portions of the case for $85 million. See “DOJ, Florida Hospital Enter $85 Million Settlement of False Claims, Stark Allegations,” Health Care Daily Rep. (BNA) (Mar. 12, 2014). 3 ATLANTA 5549886.1 oncologists received bonuses (in proportion to their personally performed services) from this pool. U.S. District Judge Gregory Parnell held that even though the bonuses were apportioned based on personally performed services, the fact that the pool included revenues from the physicians’ DHS referrals created a Stark Law violation. That is, the total pool could vary with the volume or value of the physicians’ referrals, which, Judge Parnell said, is not permitted under the Stark Law. (B) Another federal court in Florida10 recently confirmed that productivity bonuses based on volume of personally performed services (not referrals) are permitted under the Stark Law. In Schubert, the relator alleged, inter alia, that a physician’s compensation package that included base salary that required a minimum number of procedures be performed and a bonus if he performed an additional number of procedures was not fair market value. In dismissing this claim, the court held: “There is nothing inherently improper with volume based compensation arrangements, as long as they do not take into account the volume or value of referrals and the services are personally performed by the physician.”11 ii. Indirect Compensation Exception. In the case of physicians employed through a separate subsidiary of a hospital, the compensation should be structured to comply with the indirect compensation exception under the Stark Law as the physicians would not be bona fide employees of the hospital.12 The compensation paid to the physician must be fair market value for the services and not determined in a way that takes into account the volume or value of DHS referrals or other business generated by the physician for the hospital. iii. Group Practice Definition. If the hospital elects to employ the physicians through a separate entity, it could be structured to fit within the Stark Law definition of “group practice.” The primary advantage to doing so is that the physicians could share in profits of the group and/or receive credit for the “incident to” services for purposes of productivity bonus calculation.13 In each case, the physician’s profit share or bonus could not be determined in a manner that takes into account the volume or value of the physician’s referrals for DHS. To meet the group practice definition under the Stark Law14, the organization must meet the following elements: 10 United States ex rel. Schubert v. All Children’s Health System, Inc., Case No. 8:11-CV-01687-T-78EAJ (M.D. Fla. Nov. 15, 2013). 11 Id. at 25. 12 42 C.F.R. § 411.357(p). 13 42 C.F.R. § 411.352(i). 14 42 C.F.R. § 411.352. 4 ATLANTA 5549886.1 e. Be organized as a single legal entity; Include at least two (2) physician members (owners or employees); Each physician member must provide substantially the full range of care he/she provides through the group; Substantially all (75% or more) services must be provided by members of the group; Overhead expenses and income must be distributed according to previously determined methods; The entity must be operated as a unified business (centralized decision-making, consolidated billing and accounting); No compensation to members can be directly or indirectly based on the volume or value of referrals to the group, except certain productivity bonuses; and Members of the group must conduct no less than 75% of the physician-patient encounters. Anti-Kickback Statute (“AKS”)15 i. The AKS prohibits individuals and entities from knowingly or willingly offering, paying, soliciting or receiving any remuneration, directly or indirectly, overtly or covertly, in cash or in kind, in return for or as a way to induce a referral of items or services reimbursable, in whole or in part, by federal healthcare programs. As a criminal statute , the AKS requires intent to impose liability. Courts have held that an arrangement violates the AKS if even one purpose of the arrangement is to provide remuneration in exchange for referrals. The AKS contains a number of statutory exceptions and regulatory safe harbors; however, because it is an intent-based statute, strict compliance with a statutory exception or regulatory safe harbor is not required to avoid AKS liability. ii. The AKS has both a statutory exception16 and a regulatory safe harbor for employment relationships. In each case, compensation paid to a bona fide employee (as defined in the Internal Revenue Code) for providing services for which Medicare, Medicaid or other government programs would pay is not considered 17 15 16 17 42 U.S.C. § 1320a-7b(b). 42 U.S.C. § 1320a-7b(b)(3)(B). 42 C.F.R. § 1001.952(i). 5 ATLANTA 5549886.1 “remuneration” under the AKS. Unlike the Stark exceptions, the AKS does not require fair market value or commercial reasonableness for employment arrangements. f. Tax Considerations i. Reasonable Compensation. Regardless of whether the hospital is a tax-exempt organization under Section 501(c)(3), the reasonable compensation provisions of Section 162 of the IRC will apply. Under Section 162, an organization can pay reasonable compensation to individuals who provide services to the organization. Generally, the compensation must be treated as compensation by the parties when contracted for and paid. More importantly, in determining “reasonable compensation,” the Internal Revenue Service (“IRS”) will consider not only the duties and responsibilities of the physician, but also amounts received by physicians having similar responsibilities and holding comparable positions at similar organizations and total physician compensation from all sources must be included (i.e., base, incentive, deferred compensation). There are a number of factors the IRS considers in determining the commercial reasonableness of a physician compensation agreement, which include the following: physician’s training and experience; duties and responsibilities to be performed; time spent performing duties; organizational size; physician’s contribution to profits; economic conditions; whether the compensation is in part or in whole payment for a business or assets; salary ranges for physicians in equally comparable organizations; and independence of the board or committee that determines physician compensation arrangements.18 ii. Individual Tax Planning -- Personal Goodwill vs. Corporate Goodwill. If the transaction structure chosen is an asset purchase with the seller being a physician entity that is a closely-held C corporation, the physician owners of the seller will likely want to allocate a portion of the purchase price to personal goodwill (and, thus payable and taxable to the physicians) rather than corporate goodwill (and, thus payable and taxable to the entity and then taxed again when proceeds from the sale are distributed to the physician owners). The essence of the argument by physician owners for personal goodwill is that: (i) the individual physician, through his or her expertise or standing in the community, is the reason that patients seek out the physician entity for services; and (ii) the physician is not subject to any restrictive covenants which would prohibit the physician from leaving the practice and establishing a practice in direct competition with his or her former practice. There have been a line of cases in the U.S. Tax Court and federal courts addressing whether personal goodwill exists and the circumstances in which it is appropriate to pay for the personal goodwill in a separate transaction with that amount being deducted from the purchase price 18 Source: BNA Audioconference: Valuing Physician and Executive Compensation Arrangements: Fair Market Value & Commercial Reasonableness Thresholds presented by Robert Cimasi (January 13, 2009). 6 ATLANTA 5549886.1 for the physician entity transaction. Additionally, if there is to be a payment for personal goodwill, this raises significant valuation issues. (A) Case-law. In every case where the court has found shareholder personal goodwill to exist, there has been (i) no noncompete in existence, and (ii) no employment agreement. Martin Ice Cream Company case.19 In this case, the Tax Court said: Ownership of these intangibles cannot be attributed to [the corporation] because [the shareholder] never entered into a covenant not to compete with [the corporation] or any other agreement – not even an employment agreement – by which any of [shareholder’s] distribution agreements, and his relationships with the supermarkets, and his ice cream distribution expertise became the property of [the corporation]. . . . In the case at hand . . . [the corporation] never obtained exclusive rights to either [the shareholder’s] future services or a continuing call on the business generated by [the shareholder’s] personal relationships with the supermarket owners and the rights under his agreement with Mr. Mattus; [the corporation] never had an agreement that would have caused those relationships and rights to become [the corporation’s] property.20 Howard v. U.S. case.21. In finding no personal goodwill where dentists had a non-compete with the corporation, the U.S. District Court said: In this case, Dr. Howard was a Howard Corporation employee with a covenant not to compete with Howard Corporation from 1980 through 2003, plus 3 years, or 2005. Therefore, any goodwill generated during that time period was Howard Corporation goodwill. . . . In a professional services corporation that employs a service-providing employee, such as Dr. Howard, a two-part test is used to 19 Martin Ice Cream Company v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue, 110 TC 189 (1998). 20 Id. at pp. 29-30. 21 Howard v. U.S., 108 AFTR.2d 2011-5993 (Ninth Cir., August 29, 2011); affg 106 AFTR.2d 2010-5533 (DC Wash., July 30, 2010). 7 ATLANTA 5549886.1 determine whether the corporation or the employee is considered to be the controller of the income. . . . The first prong is whether the individual is an employee of the corporation; and the second prong is whether there is a contract showing that the individual recognizes the corporation’s control.22 Kennedy case.23 Again, the Tax Court held that no personal goodwill was appropriate to allocate. In this case, the court held that a portion of payments that the business owner/president received on the sale of his business were taxable not as capital gains on sale of capital asset/goodwill as he claimed, but rather as ordinary income/consideration for services to be performed or for his noncompete agreement. Although operative transaction agreements allocated 75% of payments to goodwill, the court found that such allocation lacked economic reality: it was effected late in negotiations as a tax-motivated afterthought; and it didn’t reflect the value of goodwill in relation to other valuable aspects of transaction. The court also cited the following facts as integral to its decision of no personal goodwill: the owner/president had promised to work for purchaser for 5 years until his planned retirement and to not compete; and he subsequently worked for purchaser for period of time without compensation. (B) Factual Analysis. The question whether personal goodwill exists, sufficient to pay for this “asset” in a separate, but contemporaneous transaction with the physician entity purchase, is a very fact-intensive analysis. Factors that may support a finding of personal goodwill include: no restrictive covenant or a very limited noncompete (i.e., very narrow territory or time limit); no employment agreement or employment is terminable at will by the employee. Factors that tend to support a finding that no personal goodwill exists include the following: an employment agreement with noncompete covenants would support a finding that any goodwill generated during the period while the shareholders were employees was that of the corporation, and tends to show that the individual recognizes the corporation’s control; an employment agreement that provides that during employment, the shareholders are acting on behalf of the corporation – implying that any goodwill created during this time was on behalf of the corporation. 22 Id. at pp. 23 James P. and Joan E. Kennedy v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue, TC Memo 2010-206 (2010). 8 ATLANTA 5549886.1 (C) Potential Risks. Where the purchaser is a tax-exempt entity and agrees to an allocation to personal goodwill, the purchaser would not be obtaining a tax benefit that it otherwise would not have and, therefore, would not have to worry about any penalties being assessed by the IRS if the IRS recharacterizes the payment. However, if challenged, the purchaser could have (i) credibility issues with the IRS if this allocation was reviewed on an audit of purchaser’s return, and (ii) any costs of litigation if this were to come up on audit. The selling entity and the shareholders could have significant tax and penalty obligations if the allocation is recharacterized as additional purchase price. iii. Tax-Exempt Entities. If the hospital involved in the arrangement is an organization recognized as tax-exempt under Section 501(c)(3) of the Internal Revenue Code of 1986, as amended (the “IRC”), then consideration must be given to laws and regulations that impact such organizations. (A) Private Inurement / Private Benefit. Such organizations must be cognizant of the private inurement24 and private benefit25 rules and regulations to maintain their tax-exempt status. Under the private inurement requirements, no part of the net earnings or charitable assets may inure to the benefit of a private individual and there is no “de minimus” exception. Additionally, there cannot be more than incidental private benefit -- a Section 501(c)(3) organization cannot benefit private interests more than incidentally in the furtherance of its purposes and the accomplishment of the public benefits involved. A tax exempt organization may not be operated for private benefit. As such, arrangements between health care organizations and physicians must be structured to ensure that private benefits are not conferred. (B) Intermediate Sanctions / Disqualified Persons. Since 1996, tax-exempt organizations have been subject to the intermediate sanctions regulations26, which were promulgated to improve compliance with Section 501(c)(3) requirements by imposing penalties on insiders (i.e., “disqualified persons”) in “excess benefit transactions.” “Disqualified persons” include voting members of the organization’s governing board, senior management and anyone who exercises “substantial influence” over the organization’s affairs during the prior five (5) years. Physicians can be “disqualified persons” depending on the amount of influence they wield. Under Section 4958, there is a “rebuttable presumption of reasonableness” process the organization can follow to approve the transaction and protect the governing body. One of the key requirements for the approval is that such approval is: by board members who do not have a conflict of interest. And that approval is given based on independent comparability data and is adequately documented in the board minutes. Additionally, under the intermediate sanctions regulations, “fair market value” is defined as 24 Treas. Reg. § 1.501(a)-1(c). 25 Treas. Reg. § 1.501 (c(3)-1(d)(ii). 26 Section 4958 of the IRC. 9 ATLANTA 5549886.1 “the price at which property or the right to use property would change hands between a willing buyer and a willing seller, neither being under any compulsion to buy, sell or transfer property or the right to use property, and both having reasonable knowledge of the relevant facts.”27 Further, under the intermediate sanctions rules, “reasonable compensation” for services is the “amount that would ordinarily be paid for like services by like enterprises (whether taxable or tax-exempt) under like circumstances.”28 (C) Form 990 Reporting. Highly compensated employees (and independent contractors and related organizations) must be reported on the tax-exempt organization’s Form 990, Return of Organizations Exempt from Income Tax, which is filed with the IRS and publicly available for inspection. Therefore, the Form 990 will be of interest to competitors, such as what happened to Covenant Medical Center in Waterloo, Iowa. A Covenant competitor obtained the Form 99029 which showed, upon comparison with salaries for similarly situated physicians, that the salaries for Covenant’s five highest paid physicians (who were specialists and surgeons) far exceeded the salary ranges paid by comparable hospitals in the area and in the United States. The competitor complained to the U.S. Senate Finance Committee (then chaired by Iowa’s Senator Charles Grassley) and to the U.S. Department of Treasury. The United States Department of Justice (“DOJ”) investigated, alleged that Covenant violated the Stark Law and the False Claims Act by overpaying these physicians, and Covenant eventually settled with the DOJ and paid $4,500,000 for the privilege of settling this matter.30 (D) Assumption of Above Market Leases. In a transaction where the hospital is assuming the real property leases of the selling entity’s practice locations, the hospital will need to determine if the rent is set at a fair market value rate. Where the selling entity and / or its physician owners have an ownership interest in the building, care must be taken to ensure the rental rate is fair market value and commercially reasonable and that the lease, and lease assignment, meet the space rental exception and safe harbor under the Stark Law and AKS, respectively. However, despite the absence of physician owners of the building, a tax-exempt hospital still must ensure that the leasing arrangement meets the requirements of tax law and be wary of assuming a lease that is above fair market value, calculated at the time of the hospital-physician practice acquisition. In such a situation, any amounts above fair market value could be characterized by the IRS as impermissible private benefit. If a tax-exempt organization engages in activities that generate more than 27 26 C.F.R. § 53.4958-4(b)(1)(i). 28 26 C.F.R. § 53.4958-4(b)(1)(ii). 29 Covenant to pay feds $4.5M to settle fraud allegations, WCFCourier.com (August 25, 2009), available online at http://wcfcourier.com/news/breaking_news/covenant-to-pay-feds-m-to-settle-fraudallegations/article_f067c049-eec9-5074-97b1-2e3334c13196.html. 30 Press Release, Department of Justice, Covenant Medical Center to Pay U.S. $4.5 Million to Resolve False Claims Act Allegations (August 25, 2009) (available online at http://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/2009/August/09civ-849.html). 10 ATLANTA 5549886.1 “insubstantial” private benefit, the tax-exempt status of the hospital and any bonded indebtedness could be jeopardized. 2. Provider Based or Freestanding a. The Office of Inspector General (“OIG”) of the Department of Health and Human Services, while recognizing the dynamics of a continually changing health care market, has nonetheless traditionally held a skeptical view of hospital ownership of physician practices. In September 1999, the OIG issued a report on this model to examine if, and how, the Medicare program would be impacted by these models, and focused primarily on the impact of post-acquisition treatment of these practices as provider-based rather than freestanding31 One of OIG’s primary recommendations from this report was to eliminate the ability to operate the acquired practices as provider-based. As recently as 2012, the Medicare Payment Advisory commission (“MedPAC”) recommended equalizing payment rates for physician services irrespective of the site of service, citing increasing hospital employment of physicians as the cause for the increasing costs of physician services.32 b. Depending on the services of a particular practice, the hospital may determine that it serves both financial (e.g., ROI) and operational purposes to make the practice “provider-based” instead of freestanding. In a provider-based location, services are billed as an outpatient department of the hospital (e.g., including a facility/technical fee) for Medicare purposes. It is unlikely that commercial payors will recognize any distinction between provider-based and freestanding locations. c. Under the provider-based model, all items and services provided in the physician practice would be billed as hospital outpatient services. Thus, the patient will receive two bills for services for which the patient previously received one bill. Physician/practitioner services and ancillary services would be billed on two forms, the UB04 for the facility fee portion of the service and the CMS 1500 for the professional component of the service. d. While provider-based services can be result in higher reimbursement, making the change is not without risks. In particular, the cost to patients will be higher as they have separate co-payments for the services, as well as may now have deductibles under private insurance plans. This can result in a loss of some referrals from outside physicians or even become a public relations concern. 31 Hospital Ownership of Physician Practices, Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Inspector General (September 1999), OEI-05-98-00110, available online at http://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-05-9800110.pdf. 32 See, Transcript of Public Hearing held by MedPAC on January 12, 2012, available online at http://www.medpac.gov/transcripts/01121312MedPAC.pdf. 11 ATLANTA 5549886.1 e. As stated above, the OIG has been concerned about the impact of providerbased facilities for years.33 The OIG Work Plan for Fiscal Year 2014 includes two items focused on this issue – completion of a review of the impact on Medicare billing and a new project comparing freestanding and provider-based facilities. f. As a preliminary matter, facilities that are on the hospital campus or remote/satellite locations can qualify for provider-based status. For this purpose, the “campus” is defined as the main hospital buildings and other structures within 250 yards of those buildings.34 A remote location must be within 35 miles of the main hospital or meet certain other specific requirements.35 g. To operate locations and bill services as provider based for any location, the hospital must comply with the Provider Based Rules36, which require: i. Licensure ii. Clinical Integration The physicians must be on staff of the hospital. Oversight and monitoring by the hospital must be the same as other hospital departments. The medical director must report to the hospital’s chief medical officer (or similar). Medical staff committees of the hospital are responsible for medical activities at the provider-based facility. Medical records are integrated with the hospital’s records. Inpatient and outpatient services of the hospital and the provide-based facility must be integrated. iii. 33 34 35 36 The provider-based location must be operated under the hospital’s license unless the state requires a separate license. Financial Integration See, e.g., OIG Work Plan for Fiscal Year 2010. 42 C.F.R. § 413.65(a)(2). 42 C.F.R. § 413.65(e)(3). 42 C.F.R. § 413.65(d). 12 ATLANTA 5549886.1 iv. The provider-based facility must operate as a cost center of the hospital. Public Awareness v. It must be clear to patients that the provider-based facility is a part of the hospital and not simply a freestanding physician clinic. Additional obligations include: The location must comply with EMTALA requirements. Physician services must be billed with the correct site-of-service code. All Medicare patients at the provider-based facility must be treated as outpatients of the hospital. g. Remote or satellite locations must also comply with the following 37 requirements : i. Same Ownership and Control. The hospital must own the provider-based location. The two entities must have the same governing body. The provider-based location must operate under the same governing documents as the hospital. The hospital must have final authority over administrative decisions, including contracting, personnel and medical staff decisions. 37 42 C.F.R. § 413.65(e). Note that additional requirements will apply for provider-based locations that are joint ventures or operated under management agreements. 13 ATLANTA 5549886.1 ii. Administration and Supervision The reporting relationship must have the same frequency, intensity, and level of accountability that exists in the relationship between the hospital and one of its existing departments. The provider-based location is under direct control of the hospital. The provide-based location is operated under the same monitoring and oversight by the hospital as any other department of the hospital, and is operated just as any other department of the hospital with regard to supervision and accountability. Services such as billing, human resources, benefits, purchasing and the like must be integrated with the hospital’s services. h. If the facility will provide physician services as well as ancillary services, the hospital must file an attestation with the Medicare Administrative Contractor. 38 For other locations, while the filing of an attestation is not mandatory, such filing will limit the hospital’s liability if CMS later determines that the facility was inappropriately billing as provider-based.39 3. Structuring the Deal – Stock or Asset Purchase? a. Structure / Successor Liability Considerations. Another key element of any physician practice acquisition is transaction structure. The structure is a determinant in whether there can be successor liability for the buyer for the seller’s pre-closing operations – if one corporation is considered the successor of another, the successor is liable for the acts and obligations of the preceding owner acquired via the transaction.40 It is not feasible to completely protect a buyer, but there are steps that can be taken to identify the risks and allocate them to the acquired entity. i. In United States v. Vernon Home Health and Deerbrook Pavilion v. Shalala the Fifth and Eighth Circuits, respectively, held that in the context of an acquisition of health care companies, even in an asset-sale transaction, if the purchaser continues to 38 39 42 C.F.R. § 413.65(a)(4). 42 C.F.R. § 413.65(k). 40 Greg Radinsky, How Health Care Attorneys Can Discern Vernon, Successor Liability and Settlement Issues, 44 ST. LOUIS U. L.J. 113, 120-21 (2000). 14 ATLANTA 5549886.1 operate with the seller’s Medicare provider number, the purchaser is liable for any Medicare overpayments and civil money penalties (“CMPs”) associated with the provider number.41 ii. It is unclear whether courts would extend Vernon and Deerbrook to assert other administrative liabilities beyond the overpayments and CMPs analyzed by the courts in those cases.42 In particular, a purchaser that does not knowingly participate in wrongdoing would have substantial arguments that the scienter requirement in many civil, criminal and administrative fraud and abuse laws, such as the False Claims Act, is not satisfied.43 Purchasers in such cases could argue that the analysis in Vernon and Deerbrook (i) is tied to liabilities arising under the payor agreement and not intent-based fraud and abuse laws, (ii) should be left to a simple return of funds to the government and (iii) that CMPs do not require a showing of scienter.44 However, with respect to the Stark Law, which doesn’t require scienter, these arguments may not be persuasive to a court or enforcement agency. iii. To reduce the risk of liability for seller’s pre-closing actions that might be imposed on the hospital, the hospital should consider obtaining a new Medicare provider number for the entity to use post-closing.45 In Delta Health Group v. United States Department of Health and Human Services, the Northern District of Florida stated that a purchaser has the choice to assume the Medicare provider number.46 It explained that with assumption of the number comes additional liability and from that it can be deduced that 41 Se, United States v. Vernon Home Health, Inc. 21 F.3d 693 (5th Cir. 1994) (holding Medicare overpayments follow the Medicare provider number); and Deerbrook Pavilion, LLC v. Shalala, 235 F.3d 1100 (8th Cir. 2000) (holding CMPs follow the Medicare provider number). 42 David Deaton, Stephen Warren, Andrew Parlen & Angie Wang, Distressed Healthcare: Significant Considerations for Buyers, Sellers, and Lenders Arising from the Intersection of Healthcare and Bankruptcy Laws, 3 J. HEALTH & LIFE SCIENCES L. 1, 30 (2010). 43 Id. 44 Id. 45 See, e.g., L. Robert Guenthner, III, The Elephant in the Conference Room: Transactions with Entities Under Investigation, 18 HEALTH LAWYER 1, 9 (2004). Additional ways to limit the risk associated with Medicare liabilities when taking the preceding entity’s Medicare provider number is to utilize: indemnification provisions, well defined liability allocations, tail insurance, estoppels as to third-party contracts, Settlement/Release agreements with government or other potential claimants, reserve powers or unwind provisions. Id. 46 Delta Health Group, Inc. v. U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services, 459 F. Supp. 2d 1207 (N.D. Fla. 2006). 15 ATLANTA 5549886.1 choosing not to take the Medicare provider number prohibits a purchaser from Medicare overpayment and CMP liability.47 iv. An asset purchase will generally allow the purchaser to limit the amount and types of liability it assumes from seller’s operation of the practice. The parties need to carefully determine what assets will be included in the purchase to best delineate which liabilities will be assumed by the hospital and which will remain with the practice. Further, in an asset transaction, the purchaser v. On the other hand, the liabilities of the physician practice would transfer to the hospital in a stock/equity purchase. Additionally, in situations where a practice is taxed as a C corporation, the physician-owners could avoid double taxation issues with a stock transaction, but it could create issues for a tax-exempt hospital acquiring that stock.48 vi. If the hospital must take on the practice's liabilities, there should be consideration given to fairly broad and strong indemnification rights of the hospital against the physician owners. vii. The upside for structuring as a stock sale versus an asset sale is that the provider numbers and Medicare and Medicaid agreements would stay in place so there would be no interruption in cash flow. However, to limit liability, the hospital should consider an asset structure and not accepting assignment of the Medicare and Medicaid provider numbers of the practice (to the extent such "non-acceptance" is allowable under state law). However, if such decision results in the hospital's need to obtain new provider numbers, it could take a considerable length of time to obtain those numbers and to get the physicians fully credentialed with payors. Consequently, the hospital will need to have a financing plan to continue operations until such numbers are obtained and can be used to bill for services provided by the practice. Also, be sure to check state law to determine if a purchaser must accept automatic assignment of the Medicaid provider agreement and all associated liabilities. b. Due Diligence. Regardless of the structure of the transaction, it is important that the hospital perform legal and financial due diligence. Legal due diligence is usually performed by in-house counsel or outside counsel and should include review of the practice’s organizational documents as well as significant contracts (particularly those with potential referral sources or that represent business relationships that otherwise implicate fraud and abuse laws). During this process it is important for the hospital to determine 47 Id. at 1221-27. 48 See IRS Exempt Organizations CPE Text for FY 2000, Kaiser and Miller, Topic U, Treas. Reg. Section 1.337(d)-4 and Exempt Organizations. A thorough analysis of tax implications for tax-exempt hospitals is beyond the scope of this paper. 16 ATLANTA 5549886.1 which contracts it will assume and reject those that it does not want or need going forward. Legal due diligence should also include review of licenses, accreditations, certificates of need, surveys, inspection reports and any other authorizations needed to operate compliantly. i. Most importantly, due diligence should focus on any pending or threatened government audits, subpoenas or other investigations, as well as on past investigations. If the seller is subject to a Corporate Integrity Agreement, a Certification of Compliance Agreement, a Deferred Prosecution Agreement, a settlement agreement or other such similar agreements with a governmental agency, the hospital will need to carefully review the obligations under such agreements and determine the impact, if any, of the obligations in those agreements on the hospital’s other operations. ii. If the seller (permissibly) discloses to the hospital, during the pendency of the negotiations, that either it or its physicians is subject to an on-going investigation, hospital should work with the seller on the handling of the investigation, and may want to be involved in the settlement negotiations with the governmental agency. c. Financial Due Diligence. Financial due diligence is generally conducted by a hospital’s accounting firm or other advisor. To assert attorney-client privilege with respect to any diligence findings by such firm, outside counsel should engage the accounting or consulting firm and the engagement letter should specify at a minimum that (a) the firm is being engaged so that outside counsel can advise its client with respect to the transaction and (b) all communication from the firm should be marked “Prepared at the Request of Counsel; Attorney Work Product/Privileged and Confidential” with all reports delivered to outside counsel. d. Billing and Coding Audits. Hospitals should also consider conducting a billing and coding audit of the target practice. Again, outside counsel should engage the auditor to protect the right to assert attorney-client privilege if needed. The results of a billing audit may impact the purchase price or physician compensation under employment agreements, as well as providing information that can help the hospital determine what training may be needed after closing. e. State Law. A number of state laws may come into play in determining the structure of the transaction. For instance, if the practice is operated as a professional corporation, it may need to be restructured before a non-physician can purchase the stock of the entity. Additionally, you may need to consider the certificate of need laws in your state if the transaction involves certain equipment and/or facilities. Likewise, the terms of any restrictive covenant in the purchase agreement (or in an employment agreement) depend on what is enforceable in a particular state. 17 ATLANTA 5549886.1 f. Stark Law. i. The Stark Law exception for isolated transactions generally applies to a practice acquisition by a hospital.49 To fit within this exception, the transaction must meet the following requirements: The amount paid must be consistent with fair market value and not determined in a manner that takes into consideration the volume or value of any referrals or other business generated between the parties. The remuneration paid must be commercially reasonable even if the physician made no referrals. No additional transactions can take place between the parties for six (6) months after the acquisition unless the other transaction meets a Stark exception and except reasonable post-closing adjustments. ii. The transaction must be an “isolated financial transaction” as defined 50 by the Stark Law. Accordingly, payment under the transaction must be in a single payment or installments that are set prior to the first payment (without taking into account the volume or value of referrals) and immediately negotiable or secured by a third party or negotiable note. iii. Any real estate leases that are assumed by the hospital must be reviewed to ensure they fit the rental of office space exception, which has the following requirements: The lease is written, signed by the parties, and specifies the premises covered by the lease. The space rented does not exceed that which is reasonable and necessary for the legitimate business purposes of the rental and is used exclusively by the lessee when being used by the lessee. The term of rental is for at least 1 year. The rental charges over the term of the lease are set in advance, consistent with fair market value, and not determined in a manner that takes into account the volume or value of any referrals or other business generated between the parties (i.e., managed care) 49 42 C.F.R. § 411.357(f). 50 42 C.F.R. § 411.351. 18 ATLANTA 5549886.1 g. The lease would be commercially reasonable even if no referrals were made between the parties. The lease meets regulatory requirements imposed by the Secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services.51 AKS. i. Although a safe harbor exists under the AKS for the sale of physician practices52, the requirements are so stringent that it will be difficult for most transactions to meet. For instance, the practice must be located in a Health Professional Shortage Area and the physician-owner must not be in a position to refer patients to the purchaser after one year. ii. Because the AKS requires intent, however, failure to fit within the narrow safe harbor does not mean the transaction would violate the AKS. “The AntiKickback Act does not prohibit hospitals from acquiring medical practices, nor does it preclude the seller-doctor from making future referrals to the buyer-hospital, provided there are no economic inducements for those referrals. To comply with the statute, the hospital must simply pay fair market value for the practice’s assets.”53 iii. Any real estate leases that are assumed by the hospital must be reviewed to ensure they fit the rental of space rental safe harbor, which has the following requirements: The lease agreement is set out in writing and signed by the parties. The lease covers all of the premises leased between the parties for the term of the lease and specifies the premises covered by the lease. If the lease is for periodic intervals of time, it must specify exactly the schedule of such intervals, their precise length, and the exact rent for such intervals. The term of the lease is for at least one year. 51 42 U.S.C. § 1395nn(e)(1); 42 C.F.R. § 411.357(a). 52 42 C.F.R. § 1001.952(e). 53 United States ex rel. Obert-Hong v. Advocate Health Care, 211 F. Supp. 2d 1045, 1049 (N. D. Ill. 2002). 19 ATLANTA 5549886.1 h. The aggregate rental charge is set in advance, is consistent with fair market value in an arms-length transaction, and is not determined in a manner that takes into account the volume or value of any referrals or business otherwise generated between the parties for which payment may be made by federal health care programs. The aggregate space rented does not exceed that which is reasonably necessary to accomplish the commercially reasonable business purpose of the rental.54 Antitrust Considerations. i. Although the ACA and other market forces may encourage hospitalphysician alignment, the parties need to also consider whether a particular transaction implicates state or federal antitrust law. While it may be obvious that antitrust analysis is required in a large hospital merger, it is important to analyze the antitrust risk of physician practice acquisitions as well. Whether a potential arrangement runs the risk of being viewed as “anticompetitive” depends on a number of factors, primarily looking at what services are involved (e.g., what specialty), what is the geographic market involved and how much of that market would be controlled by the parties in the proposed transaction. ii. In January 2014, the U.S. District Court in Idaho ordered St. Luke’s Health System to unwind its acquisition of a large multispecialty practice, Saltzer Medical Group (“Saltzer”).55 St. Luke’s had over 500 employed or contracted physicians throughout portions of Idaho and Oregon. After the Saltzer transaction, the St. Luke’s Health System included 80% of the primary care physicians in Nampa, Idaho.56 While the judge lauded the parties for their intent to improve quality, he concluded that the combination would likely have anticompetitive effects and, on February 28, 2014 entered a judgment against St. Luke’s and ordered it to divest itself of the Saltzer assets and physicians. On March 4, 2014, St. Luke’s filed a Motion for Stay Pending Appeal.57 54 42 C.F.R. 1001.952(b). 55 St. Alphonsus Medical Center,Nampa, Inc. v. St. Luke's Health System, Ltd., D. Idaho, No. 1:12-CV-560 (Jan. 24, 2014). In 2012, St. Luke’s acquired the assets of Saltzer and entered into a professional services agreement with the practice. 56 Id. at p.3. 57 Saint Alphonsus Medical Center, Nampa Inc., et al. v. St. Luke’s Health System, Ltd, and St. Luke’s Regional Medical Center, Ltd., Case No. 1:12-cv-00560-BLW (Lead Case) and Federal Trade Commission; State of Idaho v. St. Luke’s Health System, Ltd.; Saltzer Medical Group, P.A., Case No. 1:13-cv-00116-BLW. 20 ATLANTA 5549886.1 4. Valuing the Arrangement As noted in the discussions above, it is imperative that all compensation paid from a hospital to a physician -- whether as salary or payment for the purchase of the physician’s practice -- be fair market value and be commercially reasonable. Considering the reputational and financial risks of failing to comply with this requirement, an independent third party valuation is essential in the physician practice acquisition, physician employment arrangements and any real estate component to the transaction. a. Valuation Approach. In the valuation industry, there are three specific approaches that should be considered in each valuation assignment. There is no requirement to rely upon any one particular approach, but merely to demonstrate consideration of all three. A brief description of the three valuation approaches follows: i. Cost Approach: Based on the anticipated cost to recreate, replace, or replicate the asset(s). ii. Income Approach: Based on the economic benefits anticipated to be derived from the asset(s) or operations. iii. Market Approach: Based on transaction data involving similar assets or companies. b. Other Methodologies. Additionally, there are multiple methodologies that fall under one or more of the above valuation approaches. The appropriateness of utilizing one or more valuation methodologies will generally depend upon the specific facts and circumstances of the asset or organization being valued. However, generally speaking, multiple methodologies should be utilized to the extent possible and the results reconciled and/or weighted for purposes of determining the final conclusion of value. The methodologies typically applied are as follows: i. Cost approach –The cost approach is used in context of the principle of substitution, meaning would a buyer would have to pay for an equivalent asset absent the proposed acquisition. One method that is commonly used in physician practice valuation is the net asset method. In applying the net asset method, you would restate each asset and liability on the balance sheet to its fair market value amount. T hen, the liabilities would be subtracted from the assets, leaving the net asset value. This amount is also commonly referred to as the equity of the organization. It is common in physician practice valuation that not all assets are acquired or all liabilities assumed. In this instance, the net asset value attributable to the assignment would only consider those assets and liabilities subject to the acquisition and the valuation report should clearly state that this is the case. It is also common, that there may need to be a reconciliation of asset/liability amounts as of the transaction date, particularly is much time has passed since the valuation date. 21 ATLANTA 5549886.1 ii. Income approach –The methodologies employed under the income approach consider the economic benefits associated with ownership of the company or an interest in a company. The value of the interest is based upon an assessment of the earnings capacity and risk attributed to the investment. The income approach is used more commonly for larger physician practices that offer ancillary services as a component of their clinical practice and/or use mid-level providers for a portion of patient care. The reasons that these features make the use of the income approach more likely, is that ancillary services and leverage of the physician down to a mid-level provider, if there is sufficient volume to warrant such, generally results in an earnings stream over and above the costs to offer such ancillary services or employ such mid-level providers. The income approach is generally applied via use of a discounted cash flow method or capitalization of earnings method. The capitalization of earnings method is used when past financial results are stable and indicative of future earnings expectations. More commonly, a discounted cash flow method is used when there is the need to project past an event, such as the ramp up of a new service, to get to the point where earnings are stabilized. iii. Market approach – Methodologies under the market approach attempt to assign value to an organization or interest in an organization based upon the prices at which similar organizations have transacted. This comparison to market pricing is generally done through use of two methods. The first method is the private company transactions method. T he private company transactions method uses the prices paid for similar privatelyheld companies (in terms of the price as a multiple of revenue or earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization (EBITDA) generally) and attempts to value the subject company based on similar metrics. The other market approach method is the guideline public company method. In this method, the appraiser evaluates stock prices for public companies in the same segment of the industry and, after appropriate adjustments, assigns value to the subject company based on this public information. It is difficult to apply the market approach in the valuation of a physician practice. The reasons it is difficult is that: 1) there really are not any publicly-traded physician practices to base the guideline public company method on, and 2) it is difficult to find a sufficient number of private transactions with comparable features to make the applications of the transaction pricing a valid indication of fair market value. For these reasons, the market approach is not commonly used in the valuation of physician practices. b. Employment. i. The hospital needs to ensure that total compensation paid to each physician meets the Stark exception. It must be both fair market value and commercially reasonable. Tax-exempt hospitals must also make certain that the compensation does not create any private benefit or private inurement concerns. ii. The three approaches discussed above (cost, income and market) also apply in the valuation of employment compensation: 22 ATLANTA 5549886.1 (A) Cost approach – In compensation valuation, the cost approach is used in context of, what a buyer would have to pay for an equivalent service absent the proposed arrangement. An example of when this could come into play is when evaluating a call coverage compensation analysis. In this instance, the hospital can engage physicians to provide the coverage at some rate of pay or they can employ physicians or engage locum tenens physicians to provide the coverage. Other factors would be appropriate for consideration such as, whether the locum tenens physicians provide the same level of quality and continuity of care, but consideration of the replacement cost is one methodology that would be appropriate for consideration in this example. (B) Income approach – In context of compensation valuation, the methodology employed under the income approach is typically consideration of the relevant revenue stream associated with the service. Also considered under this approach is the resulting income or loss associated with the fair market value compensation. As an example, given the available collections and overhead load for a physician practice, an appraiser should consider the income/loss that results at the calculated fair market value compensation in determining the reasonableness of the valuation conclusion. (C) Market approach – For compensation valuation purposes, the methodology employed includes comparison of compensation paid for similar positions, preferably in the same or similar market. Many times this is done through a comparison of industry survey benchmark data as well as other proprietary market data that the appraiser may have from previous assignments. When comparing the industry benchmark data it is important to consider factors such as productivity, payor mix, cost of living and other factors specific to the market in question that impact compensation. iii. Make certain that the valuation expert is aware of all compensation to be paid. The analysis needs to look not only at the fair market value and reasonableness of individual components, but the entire package. If the “sum of the parts exceeds the whole” it can create commercial reasonableness and fair market value issues. In addition to payments for clinical services, compensation may include: Supervision stipends; Medical directorships; Call coverage; Research payments; Co-management arrangements; Sign-on or retention bonuses; Productivity bonuses; 23 ATLANTA 5549886.1 Quality incentives; Relocation expense reimbursement; Malpractice coverage; Excess vacation or other benefits; and Profit sharing. c. Enforcement Activity. In addition to the Halifax case discussed above, a number of qui tam cases have been initiated in the past decade leading to decisions and/or settlements over allegations that payments to physicians were in excess of fair market value or not commercially reasonable. 5. United States ex rel. Drakeford v. Tuomey, Case No. 3:05-2858-MBS (D.S.C. Oct. 2, 2013). Judgment in excess of $237 million for parttime employment arrangements in excess of fair market value. United States v. Campbell, 2011 WL 43013 (D.N.J.). Physician’s relationship with hospital did not meet the bona fide employment exception. United States ex rel. Singh v. Bradford Regional Medical Center, 752 F. Supp. 2d 602 (W.D. Pa. 2010). Payment in excess of fair market value for subleased equipment. Covenant Medical Center (Waterloo, Iowa). As discussed above, Covenant paid a $4.5 million settlement in 2009 for claims of payment in excess of fair market value to five physicians. Memorial Health University Medical Center (Savannah, Ga.) In 2008, settled Stark allegations related to employed ophthalmologists for $5.08 million. United States ex rel. Kaczmarczyk v. SCCI Hospital Houston (2004). Settled for $6.5 million in case focused on commercial reasonableness of medical director agreements. Operational Matters a. In the period between signing a purchase agreement and closing the transaction, the hospital should be taking steps to smooth the integration of the new physicians. 24 ATLANTA 5549886.1 In the diligence process (described above), make sure that appropriate personnel at the hospital are aware of contracts being assumed, licenses/accreditation needed and other administrative matters. Make certain that the hospital is aware of the full range of services provided by the practice to ensure any notifications are timely. Take time to ensure that the new providers are properly credentialed for all payors. The time required for commercial payor credentialing can be a driver for determining the closing date – without proper credentialing, the hospital will not be able to bill for services provided. b. Communication with the practice physicians and administrators is key to making the onboarding process as easy as possible, and to ensure a seamless transition as well as the successful post-closing operation by hospital of the practice's operations. Below is a sample of areas to be addressed before or immediately after a new practice joins the hospital: i. ii. iii. Compliance. Schedule training for the new employees on the corporate compliance program. In addition to HIPAA training, make sure that computers (particularly laptops, tablets, etc.) are encrypted. Add the practice to standard auditing schedules. Human Resources. Set up the physicians and other new employees to ensure they are correctly in the payroll system. Confirm whether or not the group’s employees will be able to bring any paid time off hours and what seniority level the employees are. Notify the state of transfer of employees to a new employer. Accounting Set up any new vendors on the accounts payable system. Train the practice employees on any specific processes (billing, A/P, co-pay collections, etc.) 25 ATLANTA 5549886.1 iv. v. vi. 6. Information Systems Develop and test any interfaces necessary with the practice’s legacy systems. Set up appropriate equipment, logins, etc. for access to hospital systems. Pharmacy, Purchasing, Etc. Make sure the practice understands policies and procedures for ordering supplies, drugs and other items. Add the practice locations to any services (e.g,. linen, water, janitorial, shredding) necessary to be provided. Risk Management Add the providers to professional liability policies. Review leases and ensure that coverage for facilities and equipment is sufficient. Post-Closing Matters a. Post-Closing Losses and Commercial Reasonableness. One question that has been raised based on the government’s position in Tuomey is whether physician employment that operates at a loss is, by definition, not commercially reasonable. Similarly, in Schubert58, the relator alleges that the physicians’ compensation levels created a net loss for the employing entity, an affiliate of the hospital, while benefiting the hospital. b. Revaluation. Most experts will only opine as to fair market value for two or three years. Employment agreements need to contemplate a review of the compensation to be paid, including obtaining a new fair market value opinion. 7. Other Considerations and Key Takeaways 58 Mergers, acquisitions, consolidations, and other transactions between healthcare entities will continue and are the “new” normal. Transactions between hospitals and physician practices will continue as part of this trend as well, and both parties will have a vested interest in ensuring that transition from an independent practice to a hospital-owned practice is done smoothly and quickly. Schubert, p. 3. 26 ATLANTA 5549886.1 Due diligence in these transactions is critically important. Full and unfettered access to the practice and its books, records, operations and personnel is key to being able to have the necessary assurances as to the practice’s compliance history and operating practices to gain approval of the transaction from the hospital's governing board. Have a plan to deal with any compliance issues discovered in the due diligence process. Should the transaction go forward? Require self-disclosure by the practice – and to which agency? Impact on deal terms and timing? Attorney-client privilege is essential if the hospital is dividing up the due diligence responsibilities between its advisors. For example, the financial due diligence is usually conducted by the hospital's accounting firm while the legal due diligence is conducted by the hospital's in-house and/or outside counsel. The practice and the physicians will also have a vested interest in ensuring that attorney-client privilege is maintained, particularly in the circumstance where compliance issues are found in the due diligence process. Compliance officers must be involved early in the due diligence and implementation process to identify, mitigate and prevent compliance matters. Pre-closing planning for post-closing operationalization of the transaction is one of the significant keys to successful integration of a transaction. Minimize successor liability for hospital. The deal terms and structure will dictate the level of risk to the hospital in acquiring the physician group. Will the transaction be structured as an asset or stock deal? Will the hospital take the Medicare and Medicaid numbers and continue to bill under those numbers? Consideration of the effect on hospital of existing CIA, CCA or other compliance requirements of the practice. Strong indemnification provisions and procedures with few, if any, carve-outs (e.g., no “basket” or “cap” on either party’s indemnification obligations) and with financial mechanisms to cover such indemnification obligations, such as an escrow or withhold. A reputable, competent, experienced health care valuation firm is essential in working through the fair market value and commercial reasonable aspects of a transaction and physician compensation. The valuation firm should be experienced in doing valuations in the healthcare industry and similar transactions and arrangements, and be familiar with the requisite fair market value standards that must be used to meet regulatory requirements under the Stark Law, AKS and tax law. 27 ATLANTA 5549886.1