Kuipers_pdf

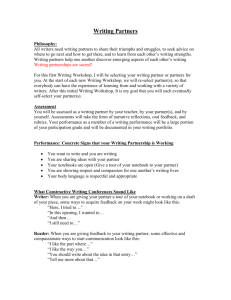

advertisement