1 Scott v. Sandford Scott v. Sandford, also known as the Dred Scott

advertisement

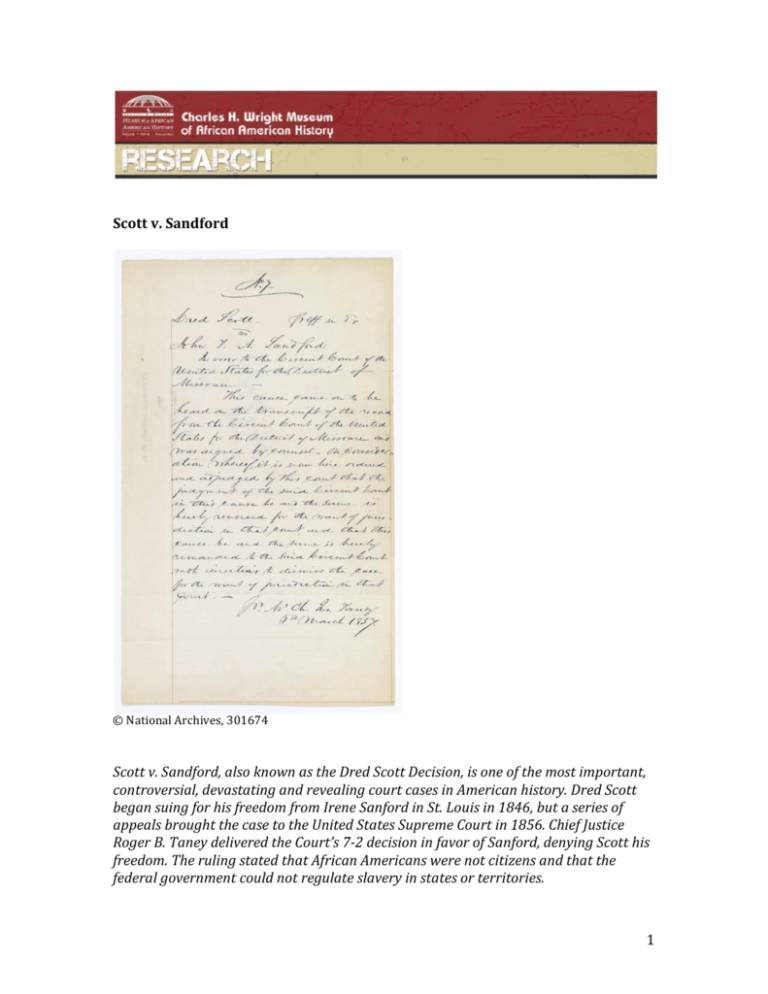

Scott v. Sandford © National Archives, 301674 Scott v. Sandford, also known as the Dred Scott Decision, is one of the most important, controversial, devastating and revealing court cases in American history. Dred Scott began suing for his freedom from Irene Sanford in St. Louis in 1846, but a series of appeals brought the case to the United States Supreme Court in 1856. Chief Justice Roger B. Taney delivered the Court’s 7-2 decision in favor of Sanford, denying Scott his freedom. The ruling stated that African Americans were not citizens and that the federal government could not regulate slavery in states or territories. 1 Scott v. Sandford, also known as the Dred Scott Decision, is one of the most important, controversial, devastating and revealing court cases in American history. By the time the case reached the Supreme Court, it had been tried in a series of circuit, district and federal courts dating back to 1846. Dred Scott had been suing for his and his family’s freedom for ten years. Scott was born into slavery in Virginia in the 1790s. In 1830 his owners, the Blow family, relocated to St. Louis, Missouri, where they sold Scott to military surgeon Dr. John Emerson (Finkleman 24). Six years later Scott met and married his wife Harriet. Her master, Major Lawrence Taliaferro, granted the couple permission to marry and transferred ownership of Harriet over to Emerson. While Dr. Emerson was fulfilling military duties, his wife Irene Sanford hired Dred Scott and his growing family out to people in Illinois and Minnesota, which were then ‘free’ states according to the Northwest Ordinance. When Dr. Emerson died in 1843, Sanford took over his estate. Scott offered to purchase his freedom from her but she refused. In 1846, Scott filed a lawsuit in a St. Louis Circuit Court. Now against slavery, Peter Blow, Scott’s original owner, provided financial and legal assistance. The case was dismissed on a technicality in June 1847 but the judge granted Scott another trial. Three years later on January 12, 1850 Judge Alexander Hamilton followed the Missouri precedent “once free, always free” and ruled that Scott and his family should be freed. Sanford, now residing in Massachusetts, appealed this decision to the Missouri Supreme Court. In November 1852, justices William Napton, James H. Birch, John F. Ryland and Chief Justice William Scott overturned Hamilton’s ruling stating that “the constitution of the State of Illinois, ratified by Congress 3d December, 1818, provides, that slaves may be hired out, from year to year, to labor at the salines without thereby working their freedom” (Missouri Supreme Court Reports 577). Determined not to give up, Scott’s lawyers used Irene Sanford’s brother as leverage to get the case into federal court. After moving to Massachusetts, Sanford transferred ownership of the Scott family to her brother, John Sanford of New York. Scott’s lawyers petitioned that the case had to be tried in a federal court on the basis of diverse citizenship (when parties in the case are residents of different states). Their appeal was successful but the Federal District Court again ruled in Sanford’s favor. Scott appealed, this time to the United States Supreme Court. On February 11, 1856, the Supreme Court began hearing oral arguments for Scott v. Sandford (a court clerk misspelled Sanford’s name and it was never corrected). St. Louis attorney Montgomery Blair argued Scott’s case before the Supreme Court, while Reverdy Johnson of Maryland and Henry S. Geyer of St. Louis represented Sanford. Blair argued that relocating a slave to a free state permanently changed his status and that slave status could not be reinstated upon re-entry into a slave state. This had been the law in Missouri until 1852—six years after Scott began suing for his freedom. As was Missouri law, he also argued that people of African descent could become citizens after gaining freedom. Johnson and Greyer countered these 2 arguments by challenging Congress’ authority to pass the Missouri Compromise of 1820. The Missouri Compromise gave Congress the right to forbid slavery in the territories (like Minnesota). They also argued that slaves were property, and property was protected by the Constitution. The case was reargued in December 1856 and the Court did not issue an official decision until May 6, 1857. The United States Supreme Court ruled 7-2 in Sanford’s favor. Chief Justice Roger B. Taney issued what is now considered the official opinion of the Court. The Supreme Court made two rulings. The first that African Americans, whether slave or free, were not citizens and were not protected by the Constitution. A free negro of the African race, whose ancestors were brought to this country and sold as slaves, is not a “citizen” within the meaning of the Constitution of the United States (Taney). The second ruling was that federal government had no power to regulate slavery in states and territories. The Constitution of the United States recognises [sic] slaves as property, and pledges the Federal Government to protect it. And Congress cannot exercise any more authority over property of that description than it may constitutionally exercise over property of any other kind (Opinion IV #4). Taney began his opinion by defining and explaining American citizenship. He stated that since there were no African American citizens at the time the Constitution was ratified, its framers did not consider blacks eligible for citizenship. This meant that not only was Dred Scott not a citizen of the United States, but his lack of citizenship meant that he had no right to try a case in court. In their second ruling, the Court adopted most of Johnson’s argument, including the ruling that the Missouri Compromise was unconstitutional (Taney). The Supreme Court’s rulings were a devastating blow to the Scott family and the anti-slavery cause. Dred Scott and his family were ordered to return to slavery following the Court’s decision. At the request of her husband, Irene Sanford transferred ownership of the Scott family back to the Blow family, who freed the family weeks later on May 26, 1857 (Finkleman 32). Sadly, Dred Scott would only enjoy one year of freedom before dying of tuberculosis on September 17, 1858. The Dred Scott Decision was immediately controversial. By the time the case reached the United States Supreme Court it had already gained national attention. The case increased the nation’s already high tensions between pro and anti slavery factions. Pro-slavery Southerners praised the Dred Scott Decision while abolitionists and other anti-slavery advocates expressed outrage. This case would prove to be among many episodes that helped fuel the Civil War. 3 Works Cited & Further Reading Finkelman, Paul. “Dred Scott vs. Sandford”. Public Debate Over Controversial Supreme Court Decisions. Ed, Melvin I. Urofsky CQ Press, 2006. 24-33. Taney, Roger B. “The Opinion of the Supreme Court” Scott v. Sandford. 1857. 4