Bacteria and Viruses

advertisement

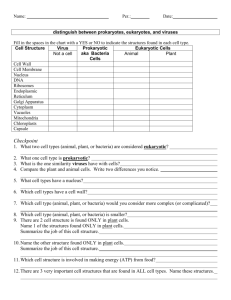

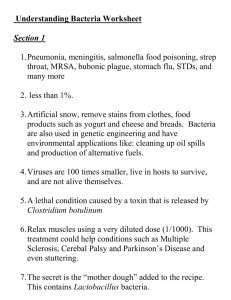

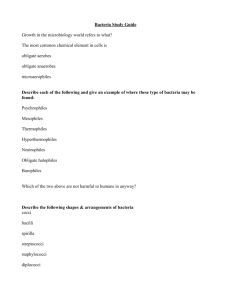

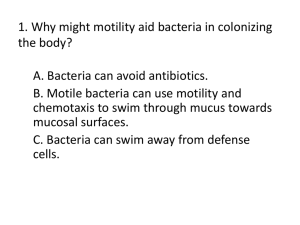

What about an intro? What is this video about? Scene 1: Making Curd: How did this single spoonful of curd become a whole bowlful of curd overnight? You know curd comes from milk, but did you ever wonder how milk gets transformed? Let’s take a look. Scene 2: Slow motion of spoon emptying into bowl When we add the spoonful of curd to the milk, we aren’t just adding curd - we are also adding hundreds of living things! This spoonful of curd is full of bacteria, tiny organisms that are too small for us to see with our naked eyes but that have big effects on us and the world around us. In the case of the curd, the spoonful we added contains a special type of bacteria called Lactobacillus. This bacteria feeds on the sugar in milk, creating lactic acid as a waste product. As the bacteria reproduce, more and more bacteria eat the milk sugar and produce more and more lactic acid as waste. This lactic acid makes the milk taste sour. It also causes the milk proteins to become denatured and coagulated, giving it the custardy thick texture we know as curd. Scene 3: Bacteria are everywhere - in our food, our water, in the air we breathe, even in our bodies! In fact, even though you can’t look around and see them, there are far more bacteria on earth than people! In your body right now, there are close to (how many?) bacteria. If you were to add up the weight of all the bacteria on the planet, it would come out to about 20 times the weight of all the people, animals, and plants on earth! That’s a lot of bacteria! (600 crore peoples weight comes arround 30000 crore kg if we taken 50 kg per person as average weight) Scene:3a Even though there are so many bacteria in the world, for a long time people did not even know bacteria existed. It wasn’t until the invention of microscopes that bacteria could be seen. In 1670, Anton Van Leuwenhoek, a Dutch(?) scientist, was surprised when he looked at a sample of water with a simple microscope and saw tiny organisms moving around! These were the first bacteria ever seen by humans. After Van Leuwenhoek’s discovery, people began finding bacteria everywhere. Scene 4: So you may be wondering, with so many bacteria out there, why don’t we get sick more often? That’s because there are actually very few kinds of bacteria that make people sick. Most bacteria don’t affect us at all, and many, like Lactobacillus making curd, are actually helpful! Bacteria perform a variety of tasks. Among other things, Bacteria help plants absorb nutrients from the soil, they help us digest food, and they cause dead plants and animals to decompose. In fact, without bacteria, humans would never have existed at all! When the earth was 4.5 billion years ago, there was no oxygen in the atmosphere. It wasn’t until bacteria started producing oxygen through photosynthesis about 2.5 billion years ago that the atmosphere could support the evolution of oxygen-breathing organisms like us. Scene 5: So now that we’ve seen some of the things they can do, what are bacteria? Well, they’re tiny, for one thing. The average bacterium is about 1 micron in length. That means if you lined up 1000 bacteria end-to-end, they’d just about cover the head of a pin. Also, bacteria are alive. That means that, like all living things, bacteria are made of cells. One cell, to be exact. Bacteria are the simplest forms of life on earth. They are neither animals nor plants - they exist in a separate category, because bacterial cells are so simple compared to plant and animal cells. We’ll take a closer look at some of these cells in order to see what we’re talking about. But first, what is a cell? Scene 6: Cells are what we call the "building blocks of life." All living things are made of cells - animals, plants, humans, and bacteria. In complex organisms -- like humans -- many cells work together in systems, with each kind of cell highly specialized to perform a certain task. In humans, there are 1014 different kinds of cells, all working together to make 200 different kinds of tissues! In single-celled organisms like bacteria, the one cell performs all the functions of life: eating and reproducing. Scene 7: Show a bacterial cell next to an animal cell (bacteria is much smaller (approx. 200x)) Here we see a bacterium next to a human cell. What’s the first thing you notice? The bacterium is much smaller, right? That’s the first sign that you’re looking at a simpler cell. Simpler cells, like bacterial cells, are unorganized, which means all of their working apparatus, including the DNA, are just sort of strewn about the inside of the cell, with no divisions between them and no specialized structures to perform particular tasks. In comparison, animal and plant cells are very organized, with many specialized structures, called organelles, that carry out all kinds of functions, like protein production and energy distribution. In particular, plant and animal cells have a nucleus, which separates the DNA from the rest of the cell, and acts as the cell’s "brain, " directing all the cell’s activities. To understand the significance of organization within a cell, think about a town with no cars, buses, trains, bikes, or machines. A really simple town. You have to walk anywhere you go, which means that everything has to be close to everything else. In comparison, imagine a town, with a bus system, trains, bikes and machines. With all this transportation, It’s much easier to get around. People can live farther away and still get the things they need. Plus, with efficient machines, more goods can be created and distributed easily, which means more people can be supported. It’s the same for cells. Bacteria eat, produce energy and proteins, and reproduce, but they have no specialized structures or transportation systems for any of these things. Therefore, everything needs to close to each other, and they are forced to be relatively small. Meanwhile, plant and animal cells have complex production centers and distribution systems, which means they can be bigger and more specialized. Scene 8: zoom in on bacterium Now, let’s take a look at what bacteria DO have and how they work. Like we mentioned earlier, all bacteria are single-celled organisms. Bacteria come in three basic shapes: spheres, shaped like footballs; rods,; and spirals The bacteria you’re looking at right now is (bacteria name), a what-shaped bacteria. Scene 9: show diagram of bacterium Most bacteria have a protective coating on the outside of their cell, called the cell wall. This cell wall is unique to bacteria - animal cells don’t have one, which is why antibiotics like penicillin kill bacteria and don’t hurt our cells - but we’ll talk about that later. Just inside the cell wall is a plasma membrane, which holds everything together. Inside the membrane is the cytoplasm, a gel-like substance that composes the bulk of the cell. Spread throughout the cytoplasm are chemical compounds that help the cell to digest food. In the cytoplasm, there are also ribosomes, organelles that make proteins. Directing the activities of the cell is a ring of DNA, called a plasmid, which is attached to the cell membrane. That’s it. Some bacteria also have motor devices like flagella, to help them move, and others have chemicals that allow them to perform photosynthesis, but overall, the internal cell structure of bacteria is pretty much the same -- and very simple. Scene 9a: So if bacteria are so simple, how do they do all the diverse things they do? Well, part of the answer is that there are many different kinds of bacteria, each of which does only one particular thing. For example One kind of bacteria eats the sugar in milk to make lactic acid, causing it to turn into curd. Another kind of bacteria lives in cow’s stomachs, breaking down all the plant tissues the cow eats that would otherwise be indigestible. So it’s not the same kind of bacteria doing all the different kinds of work. Another part of the answer is that bacteria don’t do any of these things on purpose. They’re not trying to help us out or make us sick! Bacteria’s only goal is to survive and reproduce, much like all living things. It just happens that the way bacteria live, by eating, creating waste, and reproducing, has effects on the environment around them. Sometimes these effects are good for humans; sometimes they’re not. Let’s take a look at how some bacteria live, and see how that affects the environment around them. Scene 10: zoom in on soybean field, underground, into the roots of plants.onto Bradyrhizobium japonicum Here we are, underground, tangled in the roots of a soybean plant. This is the home of a bacterium called Bradyrhizobium japonicum, or B. japonicum, which lives in the nodules in the roots of soybean plants. This is one example of a helpful bacteria - so helpful that the plant actually creates these nodules for the bacteria to live in! That’s because these bacteria can do something that the plant can’t do on its own: that is, pull nitrogen from the air and convert it into a form the plant can use. Nitrogen is one of the most important elements for organisms - it is needed to make essential proteins. Fortunately, there’s plenty of nitrogen around - it makes up about 78% of the atmosphere. But nitrogen in the air exists in a form that plants can’t use. Here’s where the B. japonicum comes in. A side effect of the normal feeding of this organism causes the nitrogen from the air to be converted into a form that’s useful for plants! This process is called "fixing nitrogen." Many plants have learned to attract these bacteria to live in their roots. In the case of soybeans, the plants create nodules where the bacteria can eat the sugars that the plant produces during photosynthesis, and the fixed nitrogen that’s created when the bacteria eat is given directly to the plant. It works out for everyone - the bacteria get a guaranteed meal, and the plants get their nitrogen! This kind of relationship, where both organisms depend on each other, is known in biology as symbiosis. Scene 11: zoom inside the human body, to picture of Clostridium tetani Now we’re seeing a different kind of bacteria altogether. This bacterium is called Clostridium tetani, or C. tetani. This is the bacterium that causes tetanus in humans, an often-fatal disease of the nervous system. C. tetani is a rod-shaped bacteria that’s normally found in soil. As a waste product of its metabolism, C. tetani also happens to produce one of the deadliest neurotoxins on the planet. When spores of C. tetani find their way into a wound on a human, they begin to grow and divide, releasing this neurotoxin into the bloodstream, which causes paralysis and respiratory failure - leading to death. Many infant deaths in developing countries are due to tetanus, following infection of the umbilical cord wound with C. tetani. Scene 12: doctor’s office Now we’ve seen how a couple of types of bacteria work and affect the world around them. So what do we do when bacteria make us sick? Antibiotics work to fight bacteria by breaking down their cell walls. When they lose this armor, bacteria become very vulnerable, and it’s easy for our body’s immune system to kill them. As we mentioned before, cell walls are unique to bacteria - animal cells don’t have them, so when we take antibiotics, the bacteria die and our cells are still just fine. Now that we’ve discussed the basics of bacterial life, lets move on. Chances are that you’ve already heard of other disease-causing organisms called viruses. Viruses are not bacteria. In fact, while bacteria are considered the simplest form of life, viruses are not considered to be alive at all! Scene 13: virus next to a bacteria (1000x) Here’s a virus next to a bacterium. Look at how small it is! You thought bacteria were small compared to animal cells. Well, next to a virus, bacteria are huge! It would take 10,000 viruses lined up end to end to cross the head of a pin. Viruses are so small because there’s not much to them - let’s look closer. Scene 14: close-up of virus A virus is simply a small chunk of DNA surrounded by a protein coating. A virus isn’t really alive - it can’t do anything expect reproduce, and it can’t even do that by itself. It must invade a living cell - a host cell. Scene 15: video of virus attacking cell (with labels) The virus ’hijacks’ the machinery of the host cell, forcing it to make copies of the virus, which then leave the cell and invade new host cells, beginning the cycle again. Sometimes the host cells are killed when the new viruses erupt, which leads to disease. Illness also occurs when the immune system senses a viral infection and attacks it, making us feel sick. Viruses cause human diseases like polio, influenza, and AIDS. Viruses can attack any kind of living cell - humans, plants, animals - even bacteria! In fact, in some places, people use certain viruses, called bacteriophages, to fight diseases that are caused by bacteria! This is possible because each virus only infects a particular kind of host cell - viruses that attack humans can’t attack bacteria and vice versa.