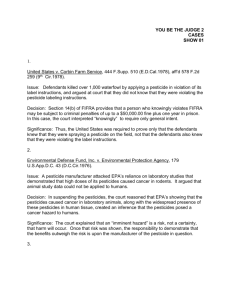

in this issue - National Litigation Bureau

advertisement