Why Do We Punish? - Colgate University

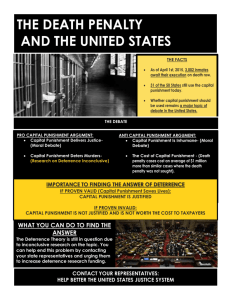

advertisement