double down-and-out: the connection between payday loans and

advertisement

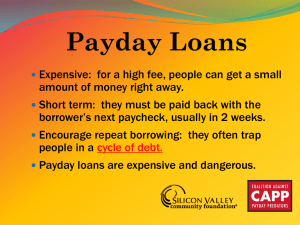

MARTIN AND TONG (FINAL) 11/9/2010 5:46 PM DOUBLE DOWN-AND-OUT: THE CONNECTION BETWEEN PAYDAY LOANS AND BANKRUPTCY Nathalie Martin* and Koo Im Tong** A payday loan is a small, triple-digit interest rate loan, typically in the range of $200 to $500, secured by the consumer‟s post-dated check or debit authorization.1 These loans were originally designed to advance money to a consumer until payday, and then the loan would be paid back in one lump sum on payday.2 A typical payday loan might allow a customer to borrow $400, for fourteen days or fewer, for a $100 fee.3 Most commonly, the loan is designed as an interest-only loan, with the interest payment, $100 in this example, due every two weeks thereafter. The principal stays out indefinitely, and after two months, the lender has recouped the original value of the principal. Several billion dollars are currently owed by American consumers for loans of this type.4 Payday and other short-term * Keleher & McLeod Professor of Law, University of New Mexico School of Law. The author thanks Ozymandias Adams for his fine research assistance and Judith Sloan, Chris Cameron, and Mark McManigal for an inspiring and informative conference. The author also thanks the National Conference of Bankruptcy Judges and the University of New Mexico School of Law for their financial support for this project. ** Associate, Moore, Berkson, and Gandarilla, Albuquerque, New Mexico. The author thanks Nathalie Martin for her generosity and encouragement and Brett Andrzejewski for his support. 1. See ConsumersUnion.org, Fact Sheet on Payday Loans, http://www.consumersunion.org/ finance/paydayfact.htm (last visited April 20, 2010). 2. See id. 3. Kept out for one year, this loan would earn interest in the amount of $2600 and the borrower would still owe the principal of $400. 4. LESLIE PARRISH & URIAH KING, CTR. FOR RESPONSIBLE LENDING, PHANTOM DEMAND: SHORT-TERM DUE DATE GENERATES NEED FOR REPEAT PAYDAY LOANS, ACCOUNTING FOR 76% OF TOTAL VOLUME 13 (2009) (“The result of these 59 million unnecessary loans is that borrowers pay about $3.5 billion in fees to avoid having to permanently part ways with the principal borrowed in one fell swoop.”). 785 07 FINAL MARTIN AND TONG (FINAL) 786 S OU TH WES TER N LA W REVIE W 11/9/2010 5:46 PM [Vol. 39 loan outlets almost tripled in number from 1999 to 2006,5 and now outnumber all McDonalds and Starbucks stores combined.6 Some claim that this is the fastest growing segment of the consumer-credit industry,7 and that as the economy falters, more and more middle-income people may use this form of credit. These loans are loathed by many because they carry such high interest rates, because customers frequently do not understand the terms of the loans, and because they arguably create a cycle of debt from which many customers cannot escape.8 In addition, payday lenders have been criticized for questionable collection tactics and for targeting minorities.9 For example, a study conducted by the Center for Responsible Lending (“CRL”), a payday lending foe, found that “[p]ayday loan stores are nearly eight times more concentrated in California‟s African-American and Latino neighborhoods as compared to white neighborhoods, draining these 5. Patrick M. Aul, Federal Usury Law for Service Members: The Talent-Nelson Amendment, 12 N.C. BANKING INST. 163, 165 (2008). One customer we spoke to noted that a shop with one employee in 2003 now has six employees. 6. Mary D., 10 Shocking Facts About Payday Loans, PAYDAY LOANS.ORG, Oct. 26, 2009, http://www.paydayloans.org/10-shocking-facts-about-payday-loans/. 7. See, e.g., CFSA, http://www.cfsa.net/ (last visited April 20, 2010) (“We invite you to explore our site to learn more about one of the fastest growing financial service industries in the United States.”); Apurva Shree, Fax Less Low Cost Payday Loan—Trouble-Free Fast Cash Loans, AMERICAN CHRONICLE, Nov. 4, 2007, http://www.americanchronicle.com/articles/view/ 42013 (“With so many factors in their favor it is no wonder that the payday lending industry is one of the fastest growing industries with many people opting for fax less low cost payday loan.”). 8. See ConsumersUnion.org, Fact Sheet on Payday Loans, http://www.consumersunion.org/ finance/paydayfact.htm (last visited April 20, 2010). 9. In one case, a customer named Floyd Watkins was “held against his will” in a payday lender‟s store by the store manager for failing to repay his loan. Valued Servs. of Ky. v. Watkins, No. 2008-CA-001204-MR, 2009 WL 1705696, at *1 (Ky. Ct. App. 2009). Watkins informed the manager that “he could not repay his loan on that day, but that he would be able to do so three days later.” Id. The manager insisted that Watkins repay the entire loan amount that day and stated that he would not be allowed to leave until he had paid in full. Id. The manager “pushed a button to lock the office door and would not allow Watkins to leave even though he repeatedly asked to do so.” Id. The manager then “telephoned her regional manager . . . and told [the regional manager] that „I have a black guy over here that refuses to pay his bill and he‟s not going to leave until he does.‟” Id. Watkins later sued for false imprisonment. Id. at *2. See also DebtConsolidationCare.com, Trihouse Enterprises, Inc. Sells How-to Manuals on PDL, http://www.debtconsolidationcare.com/getting-loan/payday-industry.html (last visited April 20, 2010) (providing debt consolidation services). This website reports on the payday loan industry‟s “intimidation sheet,” and discusses some of the methods used by the industry to collect more fees and mislead customers. Id. One manual, discussed on the website, warns lenders by stating, “You may be surprised at the number of persons unable to manage their finances.” Id. This manual also advises prospective payday lenders to “visualize a uniformed, gun toting U.S. Marshal arriving at their place of employment (to collect money). Emphasize to them that this U.S. Marshal will first ask for (their) immediate supervisor!” Id. MARTIN AND TONG (FINAL) 2010] PAY DA Y L OA NS AN D B AN KR UP T CY 11/9/2010 5:46 PM 787 communities of some $250 million in payday loan fees annually.”10 And “[e]ven after accounting for factors like income, education and poverty rates, the CRL still found that these lenders are 2.4 times more concentrated in African-American and Latino neighborhoods.”11 While at least one scholar has attempted to argue that payday loans do not create a cycle of debt, the mathematics of the situation make that difficult to imagine. Once one has used a payday loan, for example by borrowing $400 at $25 per $100 in order to pay the rent, the borrower will then owe an extra $200 every month, unless he or she can get out from under the initial loan by paying it off. That means there is $200 less discretionary income available each month for other household items or necessities, which is enough money to be significant in many households, but particularly in households already experiencing cash flow difficulties. Many scholars have previously studied the connection between payday loans and bankruptcy, and have reached varying conclusions.12 Some scholars have concluded that payday loans do not cause bankruptcy.13 The evidence they rely on suggests that once states have banned payday lending,14 residents of those states experience higher Chapter 7 bankruptcy filings, bounce more checks, and file more complaints with the Federal 10. Desiree Evans, Predatory Payday Lenders Target Black and Latino Communities, FACING SOUTH, March 27, 2009, http://southernstudies.org/2009/03/payday-lenders-targetblacks-and-latino-communities.html. 11. Id. 12. Compare Donald P. Morgan & Michael Strain, Payday Holiday: How Households Fare After Payday Credit Bans 26, (Fed. Reserve Bank of N.Y. Working Paper, Paper No. 309, 2008), available at http://newyorkfed.org/research/staff_reports/sr309.pdf (finding that Chapter 7 declarations increased in two states following the abolition of payday loans) and Petru S. Stoianovici & Michael T. Maloney, Restrictions on Credit: A Public Policy Analysis of Payday Lending 1 (2008), available at http://ssrn.com/abstract=1291278 (concluding, based on their study of state data collected between 1990 and 2006, that there is no empirical evidence to support the proposition that payday lending leads to more bankruptcy filings), with Paige M. Skiba & Jeremy Tobacman, Do Payday Loans Cause Bankruptcy? 1 (2009), available at http://papers. ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1266215 (“[F]or first-time applicants near the 20th percentile of the credit-score distribution, access to payday loans causes [C]hapter 13 bankruptcy filings over the next two years to double.”) and Robert Mayer, Payday Lending and Personal Bankruptcy, 50 CONSUMER INTERESTS ANN. 76, 81 (2004), available at http://www.luc.edu/faculty/rmayer/mayer19.pdf (finding that bankruptcy debtors who reported payday loans filed for bankruptcy with less total debt than those bankruptcy debtors who did not list payday loans); Mary Spector, Taming the Beast: Payday Loans, Regulatory Efforts, and Unintended Consequences, 57 DEPAUL L. REV. 961, 966 (2008) (“One industry study reported that 15.4% of all payday borrowers have filed for bankruptcy—compared with 3.7% of the general population—and only 41.7% own their homes—compared with 66.3% of all adults.”). 13. See, e.g., Morgan & Strain, supra note 12, at 26. 14. Naturally, these are states that at one time allowed payday lending. 07 FINAL MARTIN AND TONG (FINAL) 788 S OU TH WES TER N LA W REVIE W 11/9/2010 5:46 PM [Vol. 39 Trade Commission against lenders and debt collectors.15 Other scholars argue that payday loans do lead to increases in bankruptcy filings.16 Proponents of this view came to the conclusion, at least in part, after analyzing the common characteristics of bankruptcy petitioners who have taken out payday loans.17 This Article reviews the literature on this debate but does not weigh in on the subject of causation between bankruptcy and payday loans. Rather, it uses these studies, as well as a general discussion of bankruptcy filing and payday loans, as a backdrop for analyzing new data regarding the correlation between bankruptcy filing and the use of payday loans. This Article reports on an empirical study conducted in the state of New Mexico that measures rates of payday loan use among bankruptcy debtors from a large sample of publicly available bankruptcy data. Part I of this Article discusses the payday loan industry, its business model, how the loans work, and who the likely payday lending customer is. Part II reviews the current literature regarding the connection between payday loans and bankruptcy, and suggests some ways in which the existing literature falls short of fully answering the question of whether payday lending causes bankruptcy filing. Part III describes the new empirical study from New Mexico. This Article describes the method used to conduct this study as well as its results. In summary, our data show that from 2007 to 2009, 18.9 percent of bankruptcy debtors in New Mexico reported using payday loans. Compared to the use of payday loans reported in other studies among the general population, as well as past studies on payday loan use among bankruptcy debtors, this rate of usage is extremely high. Moreover, the correlation between bankruptcy and payday loans seems to be getting stronger, as the use of these loan products appears to be growing. We find that almost double the percentage of bankruptcy debtors reported using payday loans from 2007 to 2009, than from 2000 to 2002. Part IV of this Article concludes that while one cannot be certain that there is a causal connection between filing for bankruptcy and using payday or other short-term loans, there is a strong correlation between bankruptcy filing and payday loan use. If the increasing use of payday loans is seen as a problem, we conclude that the problem appears to be growing, despite efforts by states to cut down on the use of these loans and to curb the use of multiple loans at one time. In fact, the usage of multiple payday loans at one time also has increased drastically, as recent bankruptcy debtors, 15. Morgan & Strain, supra note 12, at 3. 16. See Skiba & Tobacman, supra note 12, at 1. 17. See Mayer, supra note 12, at 76; Skiba & Tobacman, supra note 12, at 1. MARTIN AND TONG (FINAL) 2010] PAY DA Y L OA NS AN D B AN KR UP T CY 11/9/2010 5:46 PM 789 whether individuals or families, report using far more of these types of loans simultaneously than in the past. All of this indicates that the use of multiple loans at one time is increasing, a problem states are grappling with but apparently are not solving. I. THE PAYDAY LOAN INDUSTRY AND BANKRUPTCY FILINGS: WHAT WE KNOW ABOUT EACH This Part discusses the basic business model used by the payday loan industry and general usage rates for payday lending customers from available literature on these subjects. It also describes the typical demographic of a payday lending customer. This Part then provides national statistics on bankruptcy filings, and concludes with statistics specific to New Mexico. A. Anatomy of a Payday Loan The introduction to this Article described a payday-style loan where $400 was borrowed until payday, for a fee of $25 per $100 borrowed.18 To obtain this type of loan, the customer generally provides the lender with a post-dated check for $500, and walks away with $400 in cash.19 On payday, the lender can either deposit the customer‟s check, or if the customer does not have $500, the customer can opt to “roll over” or extend the loan for another two weeks20 for an additional fee of $100. This rollover process is repeated every two weeks thereafter until the customer can pay off the full $500. This of course, is not the only form of payday loan available. For example, some states have recently passed laws intended to cap fees at $15 per $100 borrowed, which, if effective, would result in a far cheaper loan.21 These same statutes, however, define the loans covered by the $15-per$100 law as only those loans that last between fourteen and thirty-five days, require the customer to write a post-dated check, and permit the lender to make an automatic debit transaction.22 Thus, if a payday lender wishes to 18. See supra text accompanying notes 1-3. 19. See ConsumersUnion.org, Fact Sheet on Payday Loans, http://www.consumersunion.org/ finance/paydayfact.htm (last visited April 20, 2010). 20. See id. 21. See NCSL.org, Payday Lending State Statutes, http://www.ncsl.org/default.aspx?tabid= 12473 (last visited April 20, 2010). 22. See id. 07 FINAL MARTIN AND TONG (FINAL) 790 S OU TH WES TER N LA W REVIE W 11/9/2010 5:46 PM [Vol. 39 charge more than the $15 per $100 allowed by these types of statutes, all the lender must do is create a product that does not require a post-dated check or a debit transaction, or one with a duration of more than thirty-five days. This is how the industry has evolved in many states, including New Mexico, in order to bypass these newly-enacted statutes.23 Ironically, some of the products designed to exploit the loopholes in the new laws are even more profitable than the original payday loan products.24 For example, in one form of loan used in New Mexico, the customer borrows $100, to be repaid in twenty-six bi-weekly installments of $40.16 each, plus a final installment of $55.34.25 In total, this borrower would pay $100 in principal and $999.71 in interest, for an APR of 1,147 percent.26 This example shows how short-term products vary from state to state, and that not all of these products are necessarily even called “payday loans.”27 B. The Payday Loan Industry’s Profit Model In spite of these egregious fees, the payday loan industry prides itself as the fastest growing segment of the consumer credit industry.28 The success of the payday loan industry is largely the result of an aggressive marketing strategy.29 This Part reviews some of the marketing techniques employed by the payday lending industry to increase profitability. The most critical factor in the success of the payday loan industry‟s profit model is its convenient and numerous locations.30 This may explain why the number of payday loan institutions nearly tripled in a “seven-year period between 1999 and 2006.”31 23. See Mary Kane, Payday Lenders Use Loopholes to Continue High-Interest Loans, THE NEW MEXICO INDEPENDENT, Feb. 2, 2010, http://newmexicoindependent.com/46055/paydaylenders-use-loopholes-to-continue-high-interest-loans. 24. See id. 25. Posting of Felix Salmon to Reuters, http://blogs.reuters.com/felix-salmon/2010/01/07/ loan-sharking-datapoints-of-the-day/ (Jan. 6, 2010, 19:37 EST). 26. Id. This assumes the lender is not able to convince the borrower to re-borrow the principal before the loan is paid back. 27. Nevertheless, we call all these loans “payday loans” for the sake of simplicity. 28. See CFSA, http://www.cfsa.net/ (last visited April 20, 2010) (“We invite you to explore our site to learn more about one of the fastest growing financial service industries in the United States.”). 29. See Carmen M. Butler & Niloufar A. Park, Mayday Payday: Can Corporate Social Responsibility Save Payday Lenders?, 3 RUTGERS J. L. & URB. POL‟Y 119, 119, 121, 123 (2005). 30. See Aul, supra note 5, at 165. 31. Id. MARTIN AND TONG (FINAL) 2010] PAY DA Y L OA NS AN D B AN KR UP T CY 11/9/2010 5:46 PM 791 Repeat customers are also critical to profitability and constitute the vast majority of all payday lending customers.32 For example, a study by the Center for Responsible Lending (“CRL”), using data from North Carolina regulators, reports that ninety-one percent of loans are made to borrowers who take out five or more loans per year.33 Another CRL study found that seventy-six percent of payday lending business comes from repeat customers.34 A similar study of payday loan borrowers in Colorado revealed that approximately sixty-five percent of loan volume in the state comes from customers who borrow more than twelve times per year.35 In their 2005 Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (“FDIC”) study, Flannery and Samolyk report that about forty-six percent of all payday loans are either renewals of existing loans or new loans that follow immediately upon the payment of an existing loan (“rollovers”).36 Some borrowers avoid the renewal limits found in some state laws by alternating between payday lenders and then by using funds obtained from each lender to pay off the other in turn.37 Other marketing techniques used by payday lenders include offering a free payday loan to first-time borrowers,38 and offering money to existing customers for referring new ones.39 Since loans to repeat customers are less costly to administer, lenders will often encourage repeat borrowing, even going so far as to call customers as soon as a loan is paid back to offer them more money.40 Another important revenue source for the payday loan industry comes from late fees. In fact, one payday business plan advises payday lenders to 32. See KEITH ERNST ET AL., CTR. FOR RESPONSIBLE LENDING, QUANTIFYING THE ECONOMIC COST OF PREDATORY PAYDAY LENDING 5 (2004). 33. Id. at 2; Race Matters: The Concentration of Payday Lenders in African-American Neighborhoods in North Carolina, http://www.responsiblelending.org/payday-lending/researchanalysis/rr006-Race_Matters_Payday_in_NC-0305.pdf, at 3 (“91 percent of the loans go to borrowers who are caught in a cycle of debt (receive five or more loans per year).”). 34. PARRISH & KING, supra note 4, at 1. 35. Paul Chessin, Borrowing From Peter to Pay Paul: A Statistical Analysis of Colorado’s Deferred Deposit Loan Act, 83 DENV. U. L. REV. 387, 411 (2005). 36. Mark Flannery & Katherine Samolyk, Payday Lending: Do the Costs Justify the Price? 12 (2005), available at http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id= 771624 (last visited April 20, 2010) (representing an FDIC Center for Financial Research Working Paper, Paper No. 2005/09). 37. Chessin, supra note 35, at 411. 38. PARRISH & KING, supra note 4, at 3. 39. See MyCashNow.com, Quick and Affordable Cash Advances, http://www.mycashnow. com/Online-Payday-Loan-refer.php (last visited April 20, 2010) (offering $100 for each referral to My Cash Now). 40. Nathalie Martin, 1,000% Interest—Good While Supplies Last: A Study of Payday Loan Practices and Solutions, 52 ARIZ. L. REV. (forthcoming 2010). 07 FINAL MARTIN AND TONG (FINAL) 792 S OU TH WES TER N LA W REVIE W 11/9/2010 5:46 PM [Vol. 39 maximize profits on late fees by dividing one payday loan into three or more smaller loans, stating that: Late fees are a very lucrative profit center. You do not need to actually present a client‟s check(s) to the bank to have them stamp NSF [nonsufficient funds]. Purchase your own stamp! You simply say “My bank verifies funds before accepting my deposit. . . . [Unfortunately], your check was no good. The fee is $15 per check.” If you broke their payday advance into two or three [smaller] checks, you can let them slide on one 41 [late fee] if you like. There is also evidence that some lower-income people are intimidated by banks.42 To appeal to these customers, payday lenders pride themselves on creating an environment that is welcoming and friendly. In fact, payday lenders advertise that unlike banks, they provide pre-approved loans without a credit check to people with bad or no credit.43 The payday lending industry describes itself as helping people make ends meet, and denies that their product creates a debt trap.44 However, given the demographics of the payday customers in our study, the other expenses common to people within this demographic, and the way these loans are designed, it is very difficult for payday loan customers to pay 41. Center for Responsible Lending, Fact v. Fiction: The Truth About Payday Lending Industry Claims, http://www.responsiblelending.org/payday-lending/research-analysis/fact-vfiction-the-truth-about-payday-lending-industry-claims.html#five (last visited April 20, 2010) (stating that payday lenders have low losses and high profits, and claiming that payday lenders use false excuses to justify their high late fees); see also DebtConsolidationCare.com, Trihouse Enterprises, Inc. Sells How-to Manuals on PDL, http://www.debtconsolidationcare.com/gettingloan/payday-industry.html (last visited April 20, 2010) (touted as the internet‟s first get-out-of debt community). The website claims that in 2002, affordable Payday Loan Consultants, now called Trihouse Enterprises Inc., produced a business plan that it sold to people wanting to get started in the payday industry. Id. 42. See REBECCA M. BLANK, 3 FEDERAL RESERVE BANK OF BOSTON, PROMOTING BANKING SERVICES AMONG LOW-INCOME CUSTOMERS 2 (2008), http://www.bos.frb.org/comm dev/necd/2008/issue3/LMI-banking-services.pdf. 43. See, e.g., EasyLoanFast.com, Fast Cash in 1 Hour, http://www.easyloanfast.com/ (last visited April 20, 2010) (stating “No credit checks—Good credit, bad credit, no credit, slow credit—makes no difference as Credit Check not required”); see also Gregory Elliehausen, Consumers’ Use of High-Price Credit Products: Do They Know What They Are Doing? 5 (2006) (Ind. State Univ. Networks Fin. Inst. Working Paper, Paper No. 2006-WP-02), available at http://www.networksfinancialinstitute.org/Lists/Publication%20Library/Attachments/73/2006-WP -02_Elliehausen.pdf (claiming, “Unlike traditional lenders, payday loan companies do not obtain a credit bureau report”). 44. See EasyLoanFast.com, supra note 43. MARTIN AND TONG (FINAL) 2010] PAY DA Y L OA NS AN D B AN KR UP T CY 11/9/2010 5:46 PM 793 back their loans.45 Rather, as set out above, many find it necessary to continue to pay fees without ever paying off the loan.46 In sum, the business plan of short-term lenders appears to include the following: they set up conveniently-located storefronts in as many places as possible, use incentives to build a base of repeat customers, hire extremely friendly clerks who believe (to the extent possible) that they are truly helping people in need, then begin lending as much as possible while keeping repayments as low as legally permissible, and try to encourage late payments to capitalize on profitable late fees. C. Typical Payday Loan Customer Demographic Studies have consistently found that typical payday loan customers tend to be under the age of forty-five,47 have only a high school diploma or GED,48 and are disproportionately racial minorities.49 The data are supported by industry, federal government, and university based research. Data collected on the income of families who utilize payday loans are also fairly consistent across the board50 and, not surprisingly, reveal that families who used payday loans have a notably lower family income than those who did not.51 Industry reports claim that the majority of payday loan borrowers have an annual income range between $25,000 and $50,000.52 Similarly, data collected by the Federal Reserve Board in its 2007 Survey of 45. See AMANDA LOGAN & CHRISTIAN E. WELLER, CTR. FOR AMERICAN PROGRESS, WHO BORROWS FROM PAYDAY LENDERS? AN ANALYSIS OF NEWLY AVAILABLE DATA 12 (2009), http://www.americanprogress.org/issues/2009/03/pdf/payday_lending.pdf. 46. See supra text accompanying notes 19-22. 47. See WILLIAM C. APGAR, JR. & CHRISTOPHER E. HERBERT, U.S. DEP‟T HOUS. & URBAN DEV., SUBPRIME LENDING AND ALTERNATIVE FINANCIAL SERVICE PROVIDERS: A LITERATURE REVIEW AND EMPIRICAL ANALYSIS I-40 (2006), http://www.huduser.org/portal/ publications/hsgfin/sublending.html; GREGORY ELLIEHAUSEN & EDWARD C. LAWRENCE, CREDIT RESEARCH CENTER, MCDONOUGH SCHOOL OF BUSINESS, GEORGETOWN UNIVERSITY, PAYDAY ADVANCE CREDIT IN AMERICA: AN ANALYSIS OF CUSTOMER DEMAND 29 (2001), http://www.cfsa.net/downloads/analysis_customer_demand.pdf; The Community Financial Services Association of America, http://www.cfsa.net/who_we_serve.html (last visited April 20, 2010) [hereinafter “CFSA”]. 48. See LOGAN & WELLER, supra note 45 (reporting that according to the 2007 Survey of Consumer Finances, “[t]he largest share of payday loan borrowers (39 percent) had a high school diploma or equivalent General Education Development, or GED certificate, but no college degree”); see ELLIEHAUSEN & LAWRENCE, supra note 47, at 33 (finding that the largest percentage of payday loan customers had received just a high school diploma). 49. See LOGAN & WELLER, supra note 45, at 7. 50. See APGAR & HERBERT, supra note 47, at xii. 51. LOGAN & WELLER, supra note 45, at 7. 52. See CFSA, supra note 47. 07 FINAL MARTIN AND TONG (FINAL) 794 11/9/2010 5:46 PM S OU TH WES TER N LA W REVIE W [Vol. 39 Consumer Finances “show[ed] that the mean income of families who took out a payday loan was $32,614 . . . [while] the median income of payday loan borrowers was $30,892.”53 In comparison, the same survey found that the mean income of families who did not take out a payday loan was $85,473,54 which is more than twice the mean income of families who did take out a payday loan. The median income of non-payday loan borrowers was $48,397,55 which is more than one and a half times greater than the median income of payday loan borrowers. Not surprisingly, numerous studies have found that most payday loan borrowers are credit constrained.56 For example, a 2001 study found that “relative to all U.S. adults, three times the percentage of payday loan customers are seriously debt burdened and have been denied credit or not given as much credit as they applied for in the last 5 years.”57 The same study found that “[p]ayday loan customers are also four times more likely than all adults to have filed for bankruptcy.”58 These findings were confirmed again more recently by the FINRA Investor Education Foundation, which reported that alternative methods of borrowing, including payday loans, “are used disproportionately by the unbanked. Thus, lack of a bank account is likely to result in the utilization of high-cost borrowing.”59 II. THE CAUSAL CONNECTION BETWEEN PAYDAY LOANS AND BANKRUPTCY Many scholars have studied the connection between payday loans and bankruptcy, and their studies are discussed below. Some studies have concluded that payday loans do not cause bankruptcy.60 The evidence on which these studies rely suggests that once states have banned payday 53. See LOGAN & WELLER, supra note 45, at 7. 54. Id. 55. Id. 56. Michael A. Stegman, Payday Lending, 21 J. ECON. PERSPECTIVES 169, 173 (2007) (citing ELLIEHAUSEN & LAWRENCE, supra note 47, at 33). 57. Id. 58. Michael A. Stegman & Robert Faris, Payday Lending: A Business Model that Encourages Chronic Borrowing, 17 ECON. DEV. Q. 8, 15 (2003). 59. Financial Capability in the United States, FINRA Investor Educ. Found., http://www.finrafoundation.org/web/groups/foundation/@foundation/documents/foundation/p120 535.pdf (last visited Feb. 1, 2010) (“Many of the users of these alternative methods of borrowing also did not have credit cards.”). 60. See, e.g., Morgan & Strain, supra note 12, at 3. MARTIN AND TONG (FINAL) 2010] PAY DA Y L OA NS AN D B AN KR UP T CY 11/9/2010 5:46 PM 795 lending,61 residents of those states experience higher Chapter 7 bankruptcy filings, bounce more checks, and file more complaints with the Federal Trade Commission against lenders and debt collectors after abolishing payday loans.62 Other scholars argue that payday loans do lead to increases in bankruptcy filings.63 Proponents of this view base their findings, at least in part, on a case-by-case analysis of bankruptcy petitioners who have taken out payday loans, and by analyzing their common characteristics.64 These studies vary widely in their focus and the factors considered relevant in determining a causal link. While those who find no connection between payday loans and bankruptcy focus on larger trends (i.e. general comparisons of the number of bankruptcies filed in states with and without payday lenders),65 those who claim that there is a connection limit their review to the microcosm of the individual bankruptcy debtor.66 Although it is difficult to determine whether there is a definitive causal link or just a correlation between payday loans and bankruptcy, studies on the subject have identified common factors among individuals who file for bankruptcy and payday loans.67 This Part briefly reviews some of the relevant literature on bankruptcy and payday lending, and raises questions that the authors hope may be addressed in future studies. In addition to reviewing the literature on bankruptcy and payday loans, this Part also discusses a common misconception, namely that measuring financial distress in general is best accomplished by measuring bankruptcy rates. This is not the case because many financially distressed consumers do not have access to an attorney and have no assets to save in bankruptcy in any case.68 This Part also discusses payday loan usage rates among the general population, so these rates can be compared to the rates of payday usage we found in the bankruptcy data. 61. 62. 63. 64. Naturally, these are states that at one time allowed payday lending. Morgan & Strain, supra note 12, at 3. See, e.g., Skiba & Tobacman, supra note 12, at 3. See, e.g., Mayer, supra note 12, at 76-77; see also Skiba & Tobacman, supra note 12, at 4. 65. Stoianovici & Maloney, supra note 12, at 17 (“Controlling for the intensity of payday lending stores, we find that, if anything, the presence of payday stores in a state is associated with a smaller number of [C]hapter 7 bankruptcy filings. The effect is very small: [C]hapter 7 filings go down by about 1 filing per 1 million persons.”). 66. See Mayer, supra note 12, at 76. 67. See id. at 78 (concluding that debtors who take out payday loans go bankrupt more quickly, with less debt than expected). 68. Nathalie Martin, Poverty, Culture, and the Bankruptcy Code: Narratives from the Money Law Clinic, 12 CLINICAL L. REV. 203, 230 (2005); Elizabeth Warren, Jay Westbrook & Theresa Sullivan, THE FRAGILE MIDDLE CLASS 135 (2000). 07 FINAL MARTIN AND TONG (FINAL) 796 S OU TH WES TER N LA W REVIE W 11/9/2010 5:46 PM [Vol. 39 A. Surveying the Literature For his article Payday Lending and Personal Bankruptcy,69 Professor Robert Mayer collected data from a random sample of bankruptcy petitioners in three different state‟s counties over the course of three years. Based on the data he collected, Mayer calculated that a total of 9.1 percent of the bankruptcy petitions he studied listed one or more payday loans.70 From his data, Mayer also compiled mean characteristics on the bankruptcy petitioners he reviewed from two of the three counties, as well as the corresponding effects of payday loans on debt-income ratios.71 His analysis of the effects of payday loans on debt-income ratios showed that those debtors with payday loans “went bankrupt with half a year‟s gross household income less in total debt [than those debtors with no payday loans].”72 This led Mayer to conclude that payday loan debtors “go bankrupt more quickly, with less debt than we might expect given their level of income.”73 In a later study of bankruptcy debtors in Wisconsin, Mayer found that many payday loan customers take out payday loans from more than one lender, frequently in amounts that exceed their paychecks.74 As Professor Robert Mayer explains: [P]ayday advance creditors in Milwaukee County repeatedly make loans to debtors in financial crisis who already have one or more payday loans. Together these loans frequently exceed the amount of the borrower‟s next paycheck, making roll-overs inevitable. The debtor has one payday but many payday loans, and when combined in this way these loans function 75 like a large, long-term, very expensive, interest-only cash advance. For this study, Professor Mayer examined a sample of 500 bankruptcy petitions filed by residents of Milwaukee County during the summer of 2004, looking for petitions listing more than one payday loan.76 If his sample is representative of the entire population filing for bankruptcy in Milwaukee County, then roughly 825 households went bankrupt in the 69. Mayer, supra note 12, at 78. 70. Id. 71. Id. at 79-80. 72. Id. at 78. We actually find this to be counterintuitive, as we would expect the use of payday loans to put off debtor judgment day for at least as long as one could rob Peter to pay Paul. 73. Id. 74. Robert Mayer, One Payday, Many Payday Loans: Short-Term Lending Abuse in Milwaukee County, at 1 (Loyola U. of Chicago, Working Paper), http://lwvmilwaukee.org/ mayer21.pdf (last visited Feb. 4, 2010). 75. Id. at 1. 76. Id. at 2. MARTIN AND TONG (FINAL) 2010] PAY DA Y L OA NS AN D B AN KR UP T CY 11/9/2010 5:46 PM 797 county in 2003, owing more than one payday loan at a time (10.6 percent of all petitioners).77 Some petitions listed as many as nine of these loans, with the median debtor claiming one or more of these debts owed his or her entire next paycheck to payday lenders.78 Most of the debtors had been rolling over the principal for many months.79 Seventy percent of the people who listed a payday loan on their petition had more than one.80 If petitioners had any payday advances, chances are they had several. Indeed, Mayer found that almost thirty percent had four or more.81 In their article, Do Payday Loans Cause Bankruptcy?,82 Paige Skiba and Jeremy Tobacman collected data from payday loan applications submitted to a single national financial services provider. By distinguishing between the credit scores of those individuals approved for payday loans and those who were rejected, Skiba and Tobacman matched individuals based on their payday loan applications with public records on bankruptcy petitions filed in the state of Texas. Through this procedure, Skiba and Tobacman “measured the effect of payday loan access on [C]hapter 7 and [C]hapter 13 personal bankruptcy filings.”83 Based on this measurement, they found that “for first-time applicants near the 20th percentile of the credit-score distribution, access to payday loans cause[d] Chapter 13 bankruptcy filings over the next two years to double.”84 In analyzing payday loan customers for her article Taming the Beast: Payday Loans, Regulatory Efforts, and Unintended Consequences, Mary Spector reviewed studies conducted by government agencies, industry representatives, and consumer advocacy organizations.85 While noting that studies of payday loan customers vary widely depending on who conducted the study, she concludes that “the typical payday borrower does not have access to traditional credit outlets and often seeks a short-term loan because of a financial emergency.”86 To support this conclusion, Spector noted that “[o]ne industry study reported that 15.4% of all payday borrowers have 77. Id. 78. Id. 79. Id. 80. Mayer, supra note 74, at 5. 81. Id. 82. Skiba & Tobacman, supra note 12, at 8. 83. Id. at 11. 84. Id. at 1. 85. Spector, supra note 12, at 965. 86. Id. at 966; see also ELLIEHAUSEN & LAWRENCE, supra note 47, at 33, http://www.cfsa. net/downloads/analysis_customer_demand.pdf. 07 FINAL MARTIN AND TONG (FINAL) 798 S OU TH WES TER N LA W REVIE W 11/9/2010 5:46 PM [Vol. 39 filed for bankruptcy—compared with 3.7% of the general population—and only 41.7% own their homes—compared with 66.3% of all adults.”87 By contrast, Morgan and Strain restricted their study to a comparison of the “patterns of returned (bounced) checks at Federal Reserve check processing centers, complaints against lenders and debt collectors filed by households with the FTC (Federal Trade Commission), and federal bankruptcy findings” in Georgia and North Carolina before and after each state banned payday lending.88 Based on this comparison, Morgan and Strain conclude that their study provides evidence that “would-be payday borrowers” suffer more without recourse to payday loans because they are forced to bounce checks, which the authors claim is more costly than taking out a payday loan.89 Interestingly, while Morgan and Strain acknowledge that the number of Chapter 13 filings decreased after payday loans were banned in Georgia and North Carolina, they dismiss this finding as irrelevant to the relationship between bankruptcy and payday lending because “rescheduling under Chapter 13 is for filers with substantial assets to protect, while Chapter 7 (“no assets”) is for everyone else, including, as seems likely, most payday borrowers.”90 Skiba and Tobacman exclusively collected and correlated data from the state of Texas, which they acknowledge has an unlimited homestead exemption.91 This led us to wonder how their findings92 might differ in a state with either a limited or no homestead exemption. For example, would they find that access to payday loans had a measurable effect on Chapter 7 bankruptcy filings? Or would they again conclude that “[t]here are no statistically significant overall effects of access to payday loans on 87. Spector, supra note 12, at 966. Spector also concluded that most payday borrowers require “multiple loans or rollovers to extend the life of the loan. . . . Indeed, data suggests that 90% of payday loans are made to borrowers who have engaged in more than five payday transactions in the previous twelve months.” Id. at 967. 88. Morgan & Strain, supra note 12, at 2. 89. Id. at 26. Georgians and North Carolinians do not seem better off since their states outlawed payday credit: they have bounced more checks, complained more about lenders and debt collectors, and have filed for Chapter 7 (“no asset”) bankruptcy at a higher rate. The increase in bounced checks represent a potentially huge transfer from depositors to bank and credit unions. Banning payday loans did not save Georgian households $154 million per year, as the CRL projected, it cost them millions per year in returned check fees. Id. (emphasis in original). 90. Morgan & Strain, supra note 12, at 5. 91. Skiba & Tobacman, supra note 12, at 12. 92. Id. at 3 (finding that “our regression-discontinuity estimates imply a doubling of Chapter 13 bankruptcy petitions within two years of a first-time applicant‟s successful payday loan application”). MARTIN AND TONG (FINAL) 2010] PAY DA Y L OA NS AN D B AN KR UP T CY 11/9/2010 5:46 PM 799 [C]hapter 7 bankruptcy filings”?93 In addition, Skiba and Tobacman note that there is “strong evidence that [C]hapter 13 is largely used by debtors solely to avoid home foreclosures.”94 They support this conclusion again when they explain that “[a]ccording to informal communications with the PACER Service Center, debtors file under [C]hapter 13 in order to protect their homes from foreclosure.”95 This led us to wonder whether Skiba and Tobacman would agree with Morgan and Strain‟s conclusion that people who file for Chapter 7 bankruptcy have fewer assets (or “no assets” as Morgan and Strain would say) than those who file for Chapter 13 bankruptcy. Overall, Morgan and Strain‟s study seemed the least scientific and consequently the least valid because it failed to establish a causal link between the number of bounced checks and payday loans. While their study posited that the number of bounced checks, Chapter 7 bankruptcy filings, and complaints against lenders and debt collectors increased following the abolition of payday lending in the states of Georgia and North Carolina,96 it seems equally likely that these outcomes were the result of the fact that the median household income fell 6.7 percentage points in both Georgia and North Carolina over roughly the same period of time, when median household income data from those states in 1999-2000 is compared to median household income data from those states in 2003-2004.97 Finally, while Spector uses studies from government agencies, industry representatives, and consumer advocacy organizations,98 she notes that the results from each study vary widely depending on who conducted the study.99 From this observation, a formal comparison of these studies, particularly how and where the data informing each study are collected, would be useful to understanding the true characteristics of payday loan borrowers. To us, the more interesting question about bankruptcy and payday loans, however, is not whether payday loans cause bankruptcy, but rather what information we can draw about payday loan use from the bankruptcy data, including information about the frequency of use of these loans, the 93. Id. at 15. 94. Id. at 11. 95. Id. at 13. 96. Morgan & Strain, supra note 12, at 1 (stating that payday lending was banned in Georgia and North Carolina in 2004 and 2005 respectively). 97. JACK REED, ECON. POLICY BRIEF 4 tbl. 1 (Sept. 2005), available at http://www.jec. senate.gov/archive/Documents/Reports/income7sep2005.pdf. 98. Spector, supra note 12, at 965. 99. Id. 07 FINAL MARTIN AND TONG (FINAL) 800 S OU TH WES TER N LA W REVIE W 11/9/2010 5:46 PM [Vol. 39 frequency of use of multiple loans, and the increase in the use of these loans over time. B. The Danger of Comparing Payday Lending Rates and Bankruptcy Rates It is important not to assume that all financially stressed borrowers will end up in bankruptcy, as even bankruptcy is expensive and inaccessible to many Americans. One popular money management blog recently suggested we measure the current 2010 economic recovery by its own “misery index,” a combination of statistics on rates of food stamp use, bankruptcy filings, long-term unemployed, foreclosures, and credit card defaults.100 This is a hard index to argue against, as none of these misery indicators are likely to increase during good times. The entry notes that bankruptcy rates are way up in 2009, and that there were nearly as many people filing for bankruptcy as those filing for a divorce.101 Another blog found nearly 5,900 bankruptcy filings a day in 2009, though it did report a decrease in filings in December of 2009.102 While bankruptcy rates are unquestionably inching upward as a result of the recession, scholars have always known that bankruptcy is primarily a middle class phenomenon.103 Poorer people often have less access to an attorney, and also may be judgment-proof and thus find less need for bankruptcy than people with more income and more assets.104 Poorer people also have historically had less access to credit, though that may be less true today than in the past.105 In any case, given that middle class members have traditionally used bankruptcy more frequently than people of lesser means, we need to be very careful about using bankruptcy as a proxy for financial distress across all class lines. In other words, bankruptcy is a poor proxy for financial distress in general, and particularly for people in poverty. For example, New Mexico is consistently in the top three states 100. See mybudget360.com, The 5 Indicators of the Misery Index, http://www. mybudget360.com/bankruptcy-filings-to-match-divorce-filings-in-2009-15-million-358-millionamericans-on-food-stamps-11-percent-of-the-population-the-5-indicators-of-the-misery-index/ (last visited Jan. 24, 2010). 101. Id. 102. Posting of Bob Lawless to Credit Slips, http://www.creditslips.org/creditslips/ bankruptcy_data/ (Jan. 29, 2010, 13:42 EST). 103. See Warren, Westbrook & Sullivan, supra note 68, at 135. 104. See Martin, supra note 68, at 230. 105. Id. MARTIN AND TONG (FINAL) 2010] PAY DA Y L OA NS AN D B AN KR UP T CY 11/9/2010 5:46 PM 801 for poverty levels,106 and yet it is only number thirty-seven in rank for number of bankruptcy filings per capita.107 This simply means that we cannot measure all financial failure through bankruptcy filing rates. Some people are literally too broke to go bankrupt. C. Rates of Payday Loan Use So what percentage of the population uses payday loans? Good data on what percentage of the population uses payday loans are hard to come by. In consultation with the President‟s Advisory Council on Financial Literacy and the Department of the Treasury, the FINRA Investor Education Foundation commissioned a study of the financial capability of adults living in the United States.108 The first portion of this study, which reports on a nationally-projectable telephone survey of approximately 1,500 adults, was published in December of 2009.109 The data collected for this study show that only five percent of respondents had taken out a payday loan in the past five years.110 This finding is assumed to be representative of the general adult population living in the United States.111 The 2007 Survey of Consumer Finances,112 a triennial study sponsored by the Federal Reserve Board in cooperation with the Department of the Treasury, reported that 2.4 percent of families surveyed had taken out a payday loan in the previous year.113 The data collected for the 2007 Survey of Consumer Finances are similarly designed to be representative of United States families.114 106. StateMaster.com, Economy Statistics > Percent Below Poverty Level (Most Recent) by State, http://www.statemaster.com/graph/eco_per_bel_pov_lev-economy-percent-below-povertylevel (last visited Jan. 24, 2010). 107. StateMaster.com, Bankruptcy Filings (Per Capita) by State, http://www.statemaster.com/ graph/eco_ban_fil_percap-economy-bankruptcy-filings-per-capita (last visited Apr. 6, 2010). 108. See FINRA Investor Educ. Found., supra note 59, at 24. 109. See id. 110. See id. at 11. 111. See id. at 24. 112. FED. RESERVE BD., 2007 SURVEY OF CONSUMER FINANCES (2007), http://www.federalreserve.gov/pubs/oss/oss2/2007/scf2007home.html (last visited Feb. 1, 2010). 113. Brian K. Bucks et al., Changes in U.S. Family Finances from 2004 to 2007: Evidence from the Survey of Consumer Finances, 95 FED. RESERVE BD. FED. RES. BULL. A1, A47 (2009), available at http://www.federalreserve.gov/pubs/oss/oss2/2007/bull09_SCF_nobkgdscreen.pdf. 114. See id. at A1, A2, A3. 07 FINAL MARTIN AND TONG (FINAL) 802 S OU TH WES TER N LA W REVIE W 11/9/2010 5:46 PM [Vol. 39 A recent Alberta study found that approximately three percent of the citizens of that province used payday loans.115 The study from which this data was gleaned was completed by industry experts at the request of the Consumer Services Branch of the Ministry of Service Alberta.116 Thus, it is an industry study, but was commissioned by the Alberta province government.117 Another study conducted by Leger Marketing in December 2008 provided an estimate of six percent of the general population using payday loans, based on a sample size of 900.118 Overall then, the range of people in the general population that use payday loans in the United States and Canada appears to be between 2.4 percent and six percent.119 III. DESCRIPTION OF EMPIRICAL STUDY OF BANKRUPTCY AND PAYDAY LENDING In the summer of 2009, we set out to measure the incidence of payday loan usage among bankruptcy debtors in New Mexico.120 To do this, we chose one month of the year, June 2009, to gather and analyze all the bankruptcy schedules and statements of every consumer bankruptcy debtor in New Mexico. We looked first at schedule D and F to determine if there were any payday lenders listed. We had a list of all such lenders operating in New Mexico, which we had compiled in connection with another payday lending study we were conducting. Thereafter data also were collected on the occupations and income levels of all those borrowers who reported payday lenders on their schedules D and F that will be used in connection 115. Consumer Servs. Branch of the Ministry of Serv. Alberta, Gov‟t of Alberta, Payday Loan Business Regulation Consultation: A Report on Stakeholder Input by the Payday Loan Business Regulation Working Committee 15 (2009), http://paydayloanindustry.com/Canadian_Payday_ Loan_Consultation_Report_June_2009.pdf. 116. See id. at 3-4. The study was conducted from December 2008-January 2009, and consisted of two components: 1. A telephone survey of 700 Albertans including 300 users of payday loans and 400 nonusers, aged 18 years and over. Results for users are statistically accurate to within ± 5.7 percentage points, 19 times out of twenty. Results for non-users are statistically accurate to within ± 4.9 percentage points, 19 times out of 20. 2. Four focus groups, including three conducted with payday loan users (one in Edmonton, one in Calgary and one by conference call covering smaller centers) and one conducted with non-users in Edmonton. Id. 117. See id. at 3. 118. PaydayLoanIndustryBlog, New Payday Loan Industry Survey Results Available, http://paydayloanindustryblog.com/new-payday-loan-industry-survey-results-available/ (last visited Feb. 7, 2010). 119. See Bucks, supra note 114, at A47; PaydayLoanIndustryBlog, supra note 118. 120. This study was conducted by Nathalie Martin and her research assistant Ozy Adams. MARTIN AND TONG (FINAL) 2010] PAY DA Y L OA NS AN D B AN KR UP T CY 11/9/2010 5:46 PM 803 with a subsequent article. We later repeated this data-gathering process for June of 2007 and June of 2008, in order to measure whether the usage of payday loans was constant over this three-year period, in relation to the number of overall bankruptcy debtors. In total, we gathered and studied data from 1,179 petitions, 269 in 2007, 377 in 2008, and 506 in 2009. For June of 2009, we found that 14 percent of bankruptcy debtors listed at least one payday loan in their schedules, and 56.1 percent of those who had loans had more than one listed. For 2008, 23 percent of bankruptcy debtors listed at least one payday loan in their schedules, and 76.8 percent of those who had loans had more than one listed. For June of 2007, we found that 23 percent of bankruptcy debtors listed at least one payday loan in their schedules, and 76.1 percent of those had more than one listed. Under any measure, the data show that bankruptcy filers in New Mexico used a tremendous number of payday loans, and unquestionably far more than in the general population. In summary, our data show that from 2007 to 2009, an average of 18.9 percent of bankruptcy debtors in New Mexico reported using payday loans. Compared to the use of payday loans reported in other studies among the general population, as well past studies on payday loan use among bankruptcy debtors, this rate of usage is extremely high and possibly rising. Previous studies show that payday loan use among the general population ranges between 2.4 percent and 6 percent of the population.121 Payday loan usage rates as found in our study reveal a rate of usage for bankruptcy debtors at four to five times that of the general population.122 Thus, there is no denying the strong correlation between the use of payday loans and subsequent bankruptcy filings. Moreover, the correlation seems to be getting stronger, as the use of these loan products appears to be growing. In comparing Professor Mayer‟s data on New Mexico bankruptcy debtors and the use of payday loans to our own, we found that from 2007 to 2009, the percentage of bankruptcy debtors who reported using payday loans had nearly doubled. Professor Mayer reported a payday usage rate among New Mexico debtors of 10 percent as of 2000-2002.123 He reported a usage rate of 15.2 percent 121. The 2.4 percent was for a study in which people were asked if they had used a payday loan in the past year. See Bucks, supra note 114, at 47. The 6 percent came from an industry study that measured payday loan use over a person‟s entire lifetime. See PaydayLoan IndustryBlog, supra note 118. 122. Twenty-three per 100 compared to 6 per 100 on the high end, and 2.4 compared to 17 percent on the low end. 123. See Mayer, supra note 12, at 78. 07 FINAL MARTIN AND TONG (FINAL) 804 S OU TH WES TER N LA W REVIE W 11/9/2010 5:46 PM [Vol. 39 among Milwaukee debtors in 2004.124 By 2007 and 2008, we found a usage rate of 18.9 percent in New Mexico. This is a huge increase in payday loan usage among bankruptcy debtors. Moreover, while the percentage of New Mexico bankruptcy debtors using payday loans dropped from twenty-three percent in 2007 and 2008 to seventeen percent in 2009, the number of payday loans users remained more or less the same. There simply were many more bankruptcy filings in 2009, consistent with a nationwide spike.125 There also seems to be a strong correlation between payday use and bankruptcy, as studied from the perspective of the payday loan user rather than the bankruptcy debtor. An industry study found that in 1999, 15.4 percent of payday users reported filing for bankruptcy, compared to 3.7 percent of the general population.126 Thus, using a different measure, payday loan users seem to be five times more likely than the average person to file for bankruptcy. This is different from, but somewhat consistent with, our finding that bankruptcy filers are four to five times more likely to use payday loans than the general population. If use of payday loans is seen to be a problem, then the problem is growing, despite efforts by states to cut down on the use of these loans, and certainly to curb the use of multiple loans at one time. Usage of multiple payday loans at one time has increased drastically. Recent bankruptcy debtors report using far more simultaneous loans per person or family than in the past. Mayer found that 15.2 percent of the bankruptcy filers in Milwaukee in June and July of 2004 had at least one payday loan and that 10.6 percent had more than one.127 During the periods we studied, 18.9 percent had at least one payday loan and 13.2 percent had more than one. Among those with payday loans, an amazing 69.3 percent had more than one loan, 37.1 percent had more than five, and 13.8 percent had more than ten. While Mayer found that one New Mexico woman had eighteen loans back in 2000, one woman in our sample had thirty-five simultaneous loans. This is particularly remarkable, given that New Mexico passed a law in 2007 that 124. See Mayer, supra note 74, at 5. 125. Bankruptcy Filings Spike in the Area and Nationwide, WASH. POST, April 26, 2010, available at http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2010/04/23/AR20100423050 16.html (last visited May 18, 2010) (“The U.S. rate [of bankruptcy filings] last year rose 75 percent.”). 126. See ELLIEHAUSEN & LAWRENCE, supra note 12, at 46. 127. Mayer, supra note 12, at 81. He found these multiple loan so worthy of note that he dedicated an entire article to the topic, entitled One Payday, Many Payday Loans. See Mayer, supra note 74. MARTIN AND TONG (FINAL) 2010] PAY DA Y L OA NS AN D B AN KR UP T CY 11/9/2010 5:46 PM 805 allegedly limited payday loans to twenty-five percent of each person‟s gross income, and allegedly prohibited rollovers of such loans.128 All of this suggests that former studies that measure the extent to which borrowers use multiple loans at one time severely underestimate the use of multiple loans, at least among people who later file for bankruptcy. These former studies underestimate the current number of bankruptcy debtors who use these loans, and among those who have them, they underestimate the number of loans people have at one time. IV. CONCLUSION Numerous states around the country are attempting to regulate payday loans by cutting down on their costs, reducing the use of multiple loans at one time, and curbing abuses by lenders. The data reported on here suggest that these are necessary measures. The use of multiple payday loans at one time significantly curtails a consumer‟s ability to meet his or her other ongoing expenses. Multiple loans would seem to lead to bankruptcy, at least for some, assuming the consumers involved have not already filed for bankruptcy in the past eight years,129 and further assuming that they can afford a bankruptcy attorney. While we have no data to support this particular conclusion, our sense is that payday borrowers as a whole are worse off economically than bankruptcy debtors as a whole. Bankruptcy is known to be a primarily middle class remedy for over-indebtedness. Indeed, one needs a lawyer and assets to save in order to find bankruptcy worthwhile. Whether payday borrowing leads to bankruptcy or simply makes it harder to make future ends meet, there is no question that the millions of dollars consumers spend each year on short-term loan fees could be put to more productive societal use, for example, to save for emergencies, to pay the rent and buy food, or even to buy durable goods in order to fuel the manufacturing economy. Payday loans are a drain on society and particularly on society‟s most credit-constrained citizens. This Article and the data contained in it help demonstrate that the problems caused by 128. See N.M.STAT. ANN. §§ 58-15-32, -38 (West 2009). The law was entirely unsuccessful and did absolutely nothing to curb abuses by lenders because the loans covered by the new law were defined as those in which the loan duration was between fourteen and thirty-five days, and in which the lender took a post-dated check or an automatic debit right. Lenders quickly found a way around these laws. See Martin, supra note 40, at 21-22 (page numbers refer to the manuscript draft, on file with author). 129. One can only obtain a discharge in bankruptcy once every eight years. 11 U.S.C. § 727(a)(8) (2006). 07 FINAL MARTIN AND TONG (FINAL) 806 S OU TH WES TER N LA W REVIE W 11/9/2010 5:46 PM [Vol. 39 payday lending are not going away. To the contrary, they seem to be getting worse.