THE USE OF PAROL EVIDENCE IN INTERPRETATION OF PLEA

\\server05\productn\C\COL\110-3\COL303.txt

unknown Seq: 1 15-APR-10 8:24

THE USE OF PAROL EVIDENCE IN INTERPRETATION OF

PLEA AGREEMENTS

Tina M. Woehr

I

NTRODUCTION

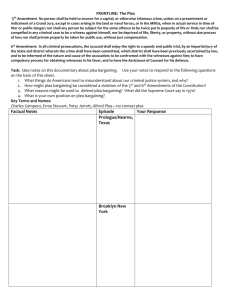

Sami Amin Al-Arian, exhausted by his ongoing and lengthy criminal case, decided to strike a plea deal with prosecutors. Later, faced with a subpoena to testify before a grand jury, Mr. Al-Arian refused to cooperate. He claimed that in exchange for his plea, the government had agreed not to require further testimony on other matters. Thus, he argued, the subpoena violated the terms of his plea agreement.

1 In United

States v. Al-Arian , Mr. Al-Arian, the prisoner-petitioner, filed a postconviction motion seeking not rescission of his guilty plea, but instead specific enforcement of what he claimed to be the terms.

2 Ultimately, the appellate court sided with the government, finding that the terms of the agreement were “clear” and “unambiguous.” 3 The Eleventh Circuit’s per curiam opinion rejected Al-Arian’s claims, which were based on agreements and statements made by the government during the course of his plea negotiations.

4 The court noted that the government might have misled Al-Arian, but stated that the government’s behavior could not change the written terms of the plea agreement, 5 which carried an integration clause 6 disavowing any other agreements.

7

1. United States v. Al-Arian, 514 F.3d 1184 (11th Cir. 2008) (per curiam), cert.

denied, 129 S. Ct. 288 (2008). Specifically, Al-Arian was seeking judicial enforcement of the plea agreement. He claimed that the during negotiations, the government agreed not to seek his testimony on other matters, “whether offered voluntarily or compelled by a subpoena.” Id. at 1187.

2. Id. at 1188.

3. Id. at 1194.

4. Id. at 1188.

5. Id. at 1193.

6. While students of contracts might also be familiar with the term “merger clause,” courts in the plea context tend to use the blanket term “integration clause.” Regardless, both terms refer to the “clause [in a writing that] recites that the written agreement is the parties’ final expression of their intentions,” often disavowing other agreements. Alan

Schwartz & Robert E. Scott, Contract Theory and the Limits of Contract Law, 113 Yale L.J.

541, 589 n.93 (2003). These clauses declare to the reader and judge “that the parties intended their writing to be interpreted as if it were complete,” and can serve as persuasive evidence of a complete and integrated agreement. Id. at 547. In this case, Mr. Al-Arian’s plea agreement carried a clause stating that it “constitute[d] the entire agreement between

[the parties] with respect to the aforementioned guilty plea and no other promises, agreements, or representations exist or have been made to the defendant or defendant’s attorney with regard to such guilty plea.” Plea Agreement at 14, Al-Arian, 514 F.3d 1184

(No. 8:03-CR-77-T30TBM), available at http://www.flmd.uscourts.gov/Al-Arian/8-03-cr-

00077-JSM-TBM/docs/2929176/0.pdf (on file with the Columbia Law Review ); see also Al-

Arian , 514 F.3d at 1187 (per curiam) (quoting integration clause). An integration clause can be found in most contracts. It essentially locks in the terms of the agreement to those expressed in the instrument. “An integrated agreement is a writing or writings constituting

840

\\server05\productn\C\COL\110-3\COL303.txt

unknown Seq: 2 15-APR-10 8:24

2010] PAROL EVIDENCE AND PLEA AGREEMENTS 841

While the outcome might offend some readers’ sense of fairness, the

Al-Arian court simply applied standard contract law principles. Because the court found the agreement to be an integrated and complete document, it would not permit Al-Arian to alter the terms later based on alleged prior oral insinuations or agreements.

8

Courts employ contracting principles when establishing and interpreting plea agreement terms, explicitly using language, doctrine, and remedies from commercial contracts law to solve disagreements over the meaning of disputed terms.

9 The contractual aspects of plea agreements have been thoroughly parsed by legal scholars.

10 This comparison has limits, however, as Judge Easterbrook explained: “Courts use contract as an analogy when addressing claims for the enforcement of plea bargains, excuses for nonperformance, or remedies for their breach. But plea bargains do not fit comfortably all aspects of either the legal or the economic model.” 11 The unique bargaining positions of the parties and the high stakes create special due process concerns even though contract law, a final expression of one or more terms of an agreement.” Restatement (Second) of

Contracts § 209(1) (1981). For another example of typical integration clause language, see infra note 110 and accompanying text.

7. See infra notes 159–163 and accompanying text (discussing court’s analysis of Al-

Arian’s plea agreement).

8. See Restatement (Second) of Contracts § 209(3) (“Where the parties reduce an agreement to a writing which in view of its completeness and specificity reasonably appears to be a complete agreement, it is taken to be an integrated agreement unless it is established by other evidence that the writing did not constitute a final expression.”).

9. See Santobello v. New York, 404 U.S. 257, 260 (1971) (granting defendant relief when government failed to fulfill bargain that induced him to plead guilty). A seminal case, Santobello laid the foundation for the use of contract law principles in the interpretation of plea bargain terms. See United States v. Alexander, 869 F.2d 91, 94–95

(2d Cir. 1989) (noting Santobello ’s adoption of “traditional contact remedies” for breach of plea agreement terms).

Santobello is also widely cited as the case that established the legitimacy of plea bargaining itself. For a discussion of the case, see infra notes 34–42 and accompanying text. For a more explicit use of contract language, see infra note 13 and accompanying text.

10. In the early 1990s, some prominent legal minds—Robert Scott, William Stuntz,

Frank Easterbrook, and Stephen Schulhofer—engaged in a debate published in a special symposium issue on punishment in the Yale Law Journal over the merits of these very special contracts. Scott and Stuntz explicitly framed their piece using a contract law framework of analysis, but contract language and principles permeated all three pieces.

See Frank H. Easterbrook, Plea Bargaining as Compromise, 101 Yale L.J. 1969, 1978 (1992)

(“Autonomy and efficiency support [plea bargains]. ‘Imperfections’ in bargaining reflect the imperfections of an anticipated trial.”); Stephen J. Schulhofer, Plea Bargaining as

Disaster, 101 Yale L.J. 1979, 2009 (1992) (arguing plea bargaining hurts both parties thanks to “pervasive structural impediments to efficient, welfare-enhancing transactions”);

Robert E. Scott & William J. Stuntz, Plea Bargaining as Contract, 101 Yale L.J. 1909,

1910–11 (1992) (arguing that “classical contract theory supports the freedom to bargain over criminal punishment[,] . . . [but] fundamental structural impediments in the plea bargaining context . . . may underlie the widespread antipathy to the practice” by creating risk of unjust convictions of some innocent defendants).

11. Easterbrook, supra note 10, at 1974 (citing Ricketts v. Adamson, 483 U.S. 1

(1987); Mabry v. Johnson, 467 U.S. 504 (1984); Santobello , 404 U.S. 257).

R

R

R

R

R

\\server05\productn\C\COL\110-3\COL303.txt

unknown Seq: 3 15-APR-10 8:24

842 COLUMBIA LAW REVIEW [Vol. 110:840 born in a commercial context, governs the interpretation of a plea agreement.

12 In United States v. Harvey , another case of contested plea agreement terms, the Fourth Circuit pointed to two characteristics of plea bargaining that might call for a modified application of private contract law principles:

First, the defendant’s underlying “contract” right is constitutionally based and therefore reflects concerns that differ fundamentally from and run wider than those of commercial contract law.

Second, with respect to federal prosecutions, the courts’ concerns run even wider than protection of the defendant’s individual constitutional rights—to concerns for the “honor of the government, public confidence in the fair administration of justice, and the effective administration of justice in a federal scheme of government.” 13

Professor Daniel Richman pointed to Harvey as an example of the use of the “ ‘fairness-based’ conception of contract” in the resolution of a plea dispute.

14 This conception of the plea bargain leads a court to “expansive rules that generally construe contractual ambiguities against the government and impose a broad duty of good faith dealing on prosecutors.” 15 This duty guards “defendants against many contingencies not explicitly addressed by their plea agreements.” 16

Despite the general consensus that contract principles play a strong role in plea agreement interpretation, federal circuit courts lack a unified doctrinal approach for deciding cases such as Mr. Al-Arian’s, thanks in part to the special concerns described above. To decide whether to admit evidence of agreements or promises that did not find their way into the text of the document, courts will turn to a contract law doctrine of

12. See United States v. Hamdi, 432 F.3d 115, 122–23 (2d Cir. 2005) (“Plea agreements, however, are ‘unique contracts, and we temper the application of ordinary contract principles with special due process concerns for fairness and the adequacy of procedural safeguards.’ ” (quoting United States v. Granik, 386 F.3d 404, 413 (2d Cir.

2004))).

13. 791 F.2d 294, 300 (4th Cir. 1986) (citation omitted) (quoting United States v.

Carter, 454 F.2d 426, 428 (4th Cir. 1972)).

14. Daniel C. Richman, Bargaining About Future Jeopardy, 49 Vand. L. Rev. 1181,

1213 (1996) [hereinafter Richman, Future Jeopardy]. Professor Richman adopts David

Charny’s “fairness-based” conception of contract for use in plea disputes. See David

Charny, Nonlegal Sanctions in Commercial Relationships, 104 Harv. L. Rev. 375, 386

(1990) (describing more “communitarian approach” that goes “beyond conceptions of contract based on free choice,” and offering employment contract as example). Richman compares this “fairness” framework with a very different line of Fourth Circuit plea interpretation cases involving unambiguous plea agreements, where the court views both parties as autonomous players, allowing the adjudicator to embrace a much stricter interpretation of the agreement text. Richman, Future Jeopardy, supra, at 1213–14. The

Fourth Circuit later distinguished the facts of Harvey from cases like these where “the plea agreement is unambiguous, and there is no evidence of governmental overreaching.” Id.

at 1214 n.125.

15. Richman, Future Jeopardy, supra note 14, at 1213.

16. Id.

R

\\server05\productn\C\COL\110-3\COL303.txt

unknown Seq: 4 15-APR-10 8:24

2010] PAROL EVIDENCE AND PLEA AGREEMENTS 843 interpretation called the parol evidence rule.

17 If the court finds an agreement to be a complete, or “integrated,” 18 contract, the parol evidence rule prevents parties to the agreement from pointing to “evidence of prior or contemporaneous agreements or negotiations” that contradict the contract terms.

19 Different circuits, however, differ in their application of the rule, especially when the contract at issue is a plea agreement.

Some hold that an integrated agreement precludes a party from presenting evidence of extratextual agreements. Other circuit courts follow suit, but are quick to find ways to let defendants challenging their guilty pleas triumph in opinions laced with language emphasizing special concerns intrinsic to plea agreements—implying the need for a more lenient application of the rule. Still other circuits, such as the Fourth Circuit, in the line of cases stemming from Harvey , will likewise eschew strict prohibitions if extrinsic evidence indicates any significant government “overreaching” during the course of negotiations.

20

This Note argues that courts should adopt the Fourth Circuit’s approach and allow extrinsic evidence into the picture only where the text of the plea agreement proves ambiguous or where the accused can present strong evidence of government overreaching, such as a prosecutor’s written promise made close in time to the plea agreement, but omitted from the text.

21 Part I of this Note paints the backdrop, explaining the goals and mechanics of both the plea bargain process and the parol evidence rule. Part II then examines the different approaches taken across circuits, and the resulting doctrinal confusion. Ultimately, Part III argues this confusion should be resolved by the uniform adoption of an approach modeled upon that of the Fourth Circuit.

I. B

ARGAINING FOR

G

UILTY

: C

ONTRACT

P

RINCIPLES AND

P

LEA

B

ARGAINS

The parties in a criminal case may opt to bypass the trial process by reaching an agreement, or plea bargain, through a negotiation process.

In other words, plea bargains are contracts, albeit very special contracts.

Plea bargains have proved crucial to the criminal justice system.

22 The parol evidence rule, on the other hand, is a fundamental doctrine of contractual interpretation studied by law students in first-year contracts courses and by transactional lawyers alike. This fundamental rule pre-

17. For more on the rule, see infra Part I.B.

18. For a discussion on completely integrated and partially integrated agreements, see infra notes 50–62 and accompanying text.

19. Restatement (Second) of Contracts § 215 (1981).

20. United States v. Harvey, 791 F.2d 294, 300 (4th Cir. 1986); see also infra Part II.B

(describing overreaching approach). For elaboration on the doctrinal mess, see infra Part

II.

21. Restatement (Second) of Contracts § 215. For a fuller explanation of the rule, see infra Part I.B. For an example of such a promise in a cover letter but not in the plea agreement, see infra notes 141–146 and accompanying text.

22. See infra notes 24–25 and accompanying text (providing statistics about frequency of plea bargains).

R

R

R

\\server05\productn\C\COL\110-3\COL303.txt

unknown Seq: 5 15-APR-10 8:24

844 COLUMBIA LAW REVIEW [Vol. 110:840 vents any prior or contemporaneous agreements (oral or written) from modifying an integrated agreement.

23 More than mere commercial or monetary concerns, however, are at stake in the plea bargaining context.

A discussion of the interaction between the parol evidence rule and the plea agreement will first require an explanation of each.

Part I.A discusses the plea bargaining process, followed by Part I.B, which summarizes the history, purpose, and substance of the parol evidence rule. The relationship between the two doctrines creates the question that this Note seeks to answer: To what extent should a commercial contracting rule such as the parol evidence rule apply in plea bargain interpretation?

A.

Plea Bargains

Convictions obtained through guilty pleas play a major and indispensable role in the United States criminal justice system; a vast majority of criminal defendants convicted and sentenced never actually go to trial, entering a guilty plea instead.

24 In the 2008 fiscal year, of the 82,451 defendants whose cases resulted in a conviction and sentence in federal district courts, 79,842, or over 96.8%, entered a plea of guilty.

25

Under Rule 11 of the Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure, a criminal defendant may enter a guilty plea provided the plea is voluntary and has a factual basis.

26 Before accepting the plea, the court must advise and question the defendant in open court to ensure she understands the rights being waived and the consequences.

27 A plea of guilty or nolo con-

23. Restatement (Second) of Contracts § 215. An integrated contract is designed to be the final formulation of the agreement, to the exclusion of all others. Often contracts will use an integration clause, disavowing all other agreements. For a discussion on integration clauses, see supra note 6.

24. James C. Duff, Admin. Office of the U.S. Courts, Judicial Business of the United

States Courts: 2008 Annual Report of the Director 244–47 tbl.D-4 (2009), available at http://www.uscourts.gov/judbus2008/JudicialBusinespdfversion.pdf (on file with the

Columbia Law Review ).

25. Id.

26. Fed. R. Crim. P. 11(b)(2)–(3). The Rule specifically classifies plea agreements as meeting the voluntariness requirement by noting that the court is to “determine that the plea is voluntary and did not result from force, threats, or promises (other than promises in a plea agreement).” Id. at 11(b)(2); see also infra note 39 (describing requirement that pleas must be entered into intelligently and voluntarily).

27. Fed. R. Crim. P. 11(b)(1). The court must advise and question the defendant about her rights regarding trial—such as the government’s right to use statements defendant makes under oath, her right not to plead guilty, the right to jury trial, the right to counsel, the rights of confrontation and cross-examination at trial—and the waiver of these trial rights through a plea. The court must also discuss the nature of the charges, maximum and mandatory minimum penalties, forfeitures, restitution, and terms in a plea agreement waiving the right to appeal or to collaterally attack the sentence, among other things. Id. In theory, the substantial amount of mandatory discussion of consequences should deter the accused from rushing into an agreement without being informed as to all the terms, but defendants often have other motivations driving a guilty plea, such as a desire for a lesser sentence. For a discussion of the benefits of plea bargains for

R

R

\\server05\productn\C\COL\110-3\COL303.txt

unknown Seq: 6 15-APR-10 8:24

2010] PAROL EVIDENCE AND PLEA AGREEMENTS 845 tendere may not be withdrawn by the defendant, and “may be set aside only on direct appeal or collateral attack.” 28 Rule 11(c) lays out “Plea

Agreement Procedure,” listing the government’s bargaining chips and requiring the agreement reached to be disclosed in open court, unless good cause can be shown to disclose it in camera.

29 A plea agreement is typically entered as a signed written document stating the agreed-upon terms, which waive some of the defendant’s rights at trial.

30

Guilty pleas conserve judicial resources, allowing prosecutors to prosecute more cases in a shorter period of time.

31 Moreover, defendants often find that entering a plea of guilty can shorten their sentences; 32 defendants (as well as for prosecutors), see infra notes 31–33, 42–43, and accompanying text.

28. Fed. R. Crim. P. 11(e). A plea of nolo contendere is taken as “indisputably tantamount to a conviction” for the purposes of sentencing, though “it is not necessarily tantamount to an admission of factual guilt.” United States v. Poellnitz, 372 F.3d 562, 566

(3d Cir. 2004) (citation omitted). Unlike a guilty plea, however, “a plea of nolo contendere may not be used against the defendant in a civil action based on same acts.” 21

Am. Jur. 2d Criminal Law § 685 (2008) (footnote omitted). Rule 410 of the Federal Rules of Evidence codified the principle that “evidence of [a nolo plea] is not, in any civil or criminal proceeding, admissible against the defendant who made the plea or was a participant in the plea discussions.” Fed. R. Evid. 410(2). This rests in part on the tenuous concept that a nolo plea “does not constitute a conviction nor hence a determination of guilt. It is only a confession of the well-pleaded facts in the charge. It does not dispose the case.” Lott v. United States, 367 U.S. 421, 426 (1961) (internal quotation marks omitted).

29. Fed. R. Crim. P. 11(c)(1)–(2). The prosecutor has a wide array of discretionary tools at her disposal that can have a major impact on the outcome for the defendant. See id. at 11(c)(1). Federal Rule of Criminal Procedure 11(c)(1) specifies that, in reaching the agreement, the government may (A) move to dismiss or choose not to bring other charges, (B) “recommend[ ] or agree not to oppose defendant’s request[ ] that a specific sentence or sentencing range is the appropriate disposition of the case, or that a particular provision of the Sentencing Guidelines, or policy statement, or sentencing factor does or does not apply,” or (C) commit to a binding version of (B) by agreeing “that a specific sentence or sentencing range is the appropriate disposition of the case.” In scenario (C), this term of the plea agreement would bind the court once accepted. Id.

30. A copy of Mr. Al-Arian’s plea agreement, discussed in the Introduction, is available online. Plea Agreement, United States v. Al-Arian, 308 F. Supp. 2d 1322 (M.D.

Fla. 2004) (No. 8:03-CR-77-T-30TBM), available at http://www.flmd.uscourts.gov/Al-

Arian/8-03-cr-00077-JSM-TBM/docs/2929176/0.pdf (on file with the Columbia Law

Review ). For another example of the format of a plea agreement entered in a federal district court, see Plea Agreement, United States v. Pfeil, No. 08-cr-227-JDB, (D.D.C. Aug.

29, 2008), available at http://www.usdoj.gov/atr/cases/f236700/236710.pdf (on file with the Columbia Law Review ).

31. Brady v. United States, 397 U.S. 742, 752 (1970) (discussing prosecutorial advantages such as faster imposition of “punishment after an admission of guilt” and how bypassing trial conserves “scarce judicial and prosecutorial resources”); see also Santobello v. New York, 404 U.S. 257, 261 (1971) (discussing desirability of plea agreements in terms of judicial efficiency, finality of disposition, and principles underlying punishment).

32.

Brady , 397 U.S. at 752 (“For a defendant who sees slight possibility of acquittal, the advantages of pleading guilty and limiting the probable penalty are obvious—his exposure is reduced, the correctional processes can begin immediately, and the practical burdens of a trial are eliminated.”); see also Am. Bar Ass’n, Crim. Justice Standards Comm., ABA

Standards for Criminal Justice: Pleas of Guilty, 73–74 (3d. ed. 1999), available at http://

R

\\server05\productn\C\COL\110-3\COL303.txt

unknown Seq: 7 15-APR-10 8:24

846 COLUMBIA LAW REVIEW [Vol. 110:840 frequently a plea is entered after the two parties—the government and the defendant—reach an agreement, where a defendant might receive a shorter sentence, dismissal of a second or third count, or a charge of a less serious crime in exchange for her guilty plea.

33 This process of negotiation between prosecutor and defendant is commonly called plea bargaining, since the parties are out to make a deal.

Only in 1971 did the Supreme Court confirm the legitimacy of plea bargaining in the case of Santobello v. New York .

34 Prior to Santobello , plea bargaining, as the Court explained, “was a sub rosa process shrouded in secrecy and deliberately concealed by participating defendants, defense lawyers, prosecutors, and even judges.” 35 Santobello involved a conviction following a plea to a lesser-included offense entered by the defendant after the government promised to make no recommendation as to his sentencing.

36 Chief Justice Burger, writing for the Court, vacated the conviction in light of the government’s breach of the agreement, 37 holding that “when a plea rests in any significant degree on a promise or agreement of the prosecutor, so that it can be said to be part of the inducement or consideration, such promise must be fulfilled.” 38 Once the knowing, intelligent, and voluntary 39 nature of a defendant’s plea enwww.abanet.org/crimjust/standards/pleasofguilty.pdf (on file with the Columbia Law

Review ) (listing guilty plea, in conjunction with other factors, as mitigating factor to consider in final disposition or sentencing).

33. See Brady, 397 U.S. at 751 (refusing to hold that plea induced by hope of lesser penalty violates Fifth Amendment).

34.

Santobello , 404 U.S. 257.

35. See Blackledge v. Allison, 431 U.S. 63, 76 (1977) (explaining how plea bargaining became “visible” and “accepted” element in criminal adjudication after Santobello ).

36.

Santobello , 404 U.S. at 258–60.

37. Id. at 263. Unlike examples of overreaching, here the prosecutor who had originally negotiated Santobello’s plea was replaced with a new prosecutor who,

“apparently ignorant of his colleague’s commitment,” recommended the maximum sentence of one-year imprisonment, which was imposed. Id. at 259–60. In vacating the judgment, the Court explained that the inadvertent nature of the breach did not “lessen its impact,” and that the “prosecutor’s office [had] the burden of ‘letting the left hand know what the right hand is doing’ or has done.” Id. at 262. This holding—that ignorance is no excuse—mirrors the idea that unilateral misunderstanding by a defendant of the terms of his guilty plea cannot serve as grounds for rescission. See infra note 193 and accompanying text.

38.

Santobello , 404 U.S. at 262. By simply vacating the conviction on the grounds of a government failure to keep its promise, as opposed to a vacatur based on the existence of a plea bargain itself, the Court would have implicitly acknowledged the practice of plea bargaining. Burger’s opinion, however, went even further by explaining the requirements for the process: The plea must “be voluntary and knowing and if it was induced by promises, the essence of those promises must in some way be made known.” Id. at 261–62.

39. A valid plea must be entered into intelligently and voluntarily, as opposed to a plea “induced by threats (or promises to discontinue improper harassment), misrepresentation (including unfulfilled or unfulfillable promises), or perhaps by promises that are by their nature improper as having no proper relationship to the prosecutor’s business (e.g. bribes).” Mabry v. Johnson, 467 U.S. 504, 509 (1984) (internal quotation marks omitted) (quoting Brady v. United States, 397 U.S. 742, 755 (1970)); see

R

\\server05\productn\C\COL\110-3\COL303.txt

unknown Seq: 8 15-APR-10 8:24

2010] PAROL EVIDENCE AND PLEA AGREEMENTS 847 tered with the assistance of counsel has been established, collateral attacks seeking withdrawal are prohibited unless “the consensual character of the plea is called into question.” 40 Chief Justice Burger described pleas and plea negotiations as not only “essential” but also “highly desirable” since they promote judicial economy, lead to quick and final dispositions of cases, avoid problems related to pretrial confinement and release, and cut down on the time between charge and disposition.

41

The opinion declared that the ideal plea bargain process meets the voluntariness and intelligence requirements because, at least in theory, both parties will benefit when defense counsel offers a guilty plea in exchange for sentencing concessions.

42 Many academics share this view of plea bargaining as a mutually beneficial process:

The parties to these settlements trade various risks and entitlements: the defendant relinquishes the right to go to trial (along with any chance of acquittal), while the prosecutor gives up the entitlement to seek the highest sentence or pursue the most serious charges possible. The resulting bargains differ predictably from what would have happened had the same cases been taken to trial. Defendants who bargain for a plea serve lower sentences than those who do not. On the other hand, everyone who pleads guilty is, by definition, convicted, while a substantial minority of those who go to trial are acquitted.

43 also Boykin v. Alabama, 395 U.S. 238, 242 (1969) (finding trial judge failed to require affirmative showing that guilty plea was “intelligent and voluntary”).

Boykin stressed the importance of not only the stakes for defendants, but also the need for trial judges to develop a record establishing the defendant’s “full understanding of what the plea connotes and of its consequence.” Boykin , 395 U.S. at 243–44. This record can be used to defeat later challenges and “forestalls the spin-off of collateral proceedings that seek to probe murky memories.” Id. at 244 (citations omitted).

40.

Mabry , 467 U.S. at 508–09 (citing Tollett v. Henderson, 411 U.S. 258, 266–67

(1973)). Federal prisoners may file for postconviction habeas relief under 28 U.S.C.

§ 2255 (2006). A federal habeas court can vacate the judgment, upon a finding that either the “judgment was rendered without jurisdiction, or that the sentence imposed was not authorized by law or otherwise open to collateral attack, or that there has been such a denial or infringement of the constitutional rights of the prisoner as to render the judgment vulnerable to collateral attack.” 28 U.S.C. § 2255. Any claims involving technical violations of Rule 11, however, are not suitable for collateral attacks, and must be raised on direct appeal. United States v. Timmreck, 441 U.S. 780, 784–85 (1979).

41.

Santobello , 404 U.S. at 260–61 (“If every criminal charge were subjected to a fullscale trial, the States and the Federal Government would need to multiply by many times the number of judges and court facilities.”). Chief Justice Burger also claimed that shortening the time period between charge and disposition would enhance the

“rehabilitative prospects of the guilty.” Id. at 261.

42. Id.; see also Mabry , 467 U.S. at 508 (describing how requirements can be met since

“each side may obtain advantages when a guilty plea is exchanged for sentencing concessions[;] the agreement is no less voluntary than any other bargained-for exchange”).

43. Scott & Stuntz, supra note 10, at 1909 (footnote omitted). Even though he agreed with Scott and Stuntz’s defense of plea bargaining on autonomy and efficiency grounds,

Easterbrook noted that “[t]he analogy between plea bargains and contracts is far from perfect,” and pointed out the inefficiencies in the transaction costs of plea agreements that

R

\\server05\productn\C\COL\110-3\COL303.txt

unknown Seq: 9 15-APR-10 8:24

848 COLUMBIA LAW REVIEW [Vol. 110:840

B.

Contract Principles: The Parol Evidence Rule

Courts normally invoke the parol evidence rule when contracting parties have put their agreement on paper, but later a dispute arises and one party attempts to use evidence of other agreements to bolster her interpretation of the contract’s terms.

44 The parol evidence rule assists a court dealing with such disputes by “help[ing] to determine the scope of what is to be interpreted.” 45 After the parol evidence rule establishes the terms of the agreement, the court will then go on to divine the meaning of those terms.

46 On the interpretation side, courts allow extrinsic evidence in to shed light on ambiguous terms. The parol evidence rule, however, focuses on scope by establishing the terms eligible for interpretation.

47

1.

Background. — Despite its name, the parol evidence rule acts as far more than just a mere evidentiary rule; it operates as a substantive rule of contractual interpretation.

48 Invoking the rule can determine the outcome of the case, as exclusion of extrinsic evidence can effectively defeat the underlying claim of the party who aims to use that “evidence to contradict [or] perhaps even to supplement the writing.” 49 If a court cannot consider the evidence of prior or contemporaneous agreements or understandings, the text alone will continue to govern the agreement.

keep them from becoming “Pareto improvements.” Easterbrook, supra note 10, at

1974–75.

44. E. Allan Farnsworth, Contracts § 7.1, at 414 (4th ed. 2004).

45. Id.

46. See id. § 7.7, at 439 (describing process of interpretation); see also Robert E. Scott

& Jody S. Kraus, Contract Law and Theory 542–45 (4th ed. 2007) (differentiating process of identifying contract terms using parol evidence rule from actual interpretation of terms and urging students to keep questions separate even if cases do not always do so). Courts often conflate these two inquiries, and do so often in plea agreement cases. This does not come as much of a shock, given the similarities between the tasks of identifying and interpreting the terms, as both involve a general prohibition on extrinsic evidence. For example, a court might confusingly cite the rule in support of declaring a ban on the use of extrinsic evidence to shed light on the meaning of terms in a writing. For further description of cases illustrating confusion over proper use of the rule, see infra note 90. A court might simply invoke the term “parol evidence rule” to signal that it is wrestling with the role of extrinsic evidence in the case in general.

47. Scott & Kraus, supra note 46, at 543–45.

48. Farnsworth, supra note 44, § 7.2, at 416–17 (pointing to “courts and scholars, specialists in the field of evidence” to support understanding of rule as substantive). As

Professor Farnsworth concedes, courts usually prefer the decision on integration of the writing to be made by “the trial judge before the evidence goes to the jury,” like decisions involving evidentiary rules. Id. § 7.3, at 425–26. But the parol evidence rule differs from the rules of evidence, which bar “methods of proof to show a fact,” whereas “the parol evidence rule bars a showing of the fact itself.” Id. § 7.2, at 416. That is not the only misleading aspect of its name—the rule covers not only oral, or parol, negotiations, but also written agreements. Id. In modern day courts, the rule’s exclusionary function does not primarily act as an evidentiary rule, but instead aims to “affirm[ ] the primacy of a subsequent agreement over prior negotiations and even over prior agreements.” Id. at

418.

49. Id. at 415.

R

R

R

R

\\server05\productn\C\COL\110-3\COL303.txt

unknown Seq: 10 15-APR-10 8:24

2010] PAROL EVIDENCE AND PLEA AGREEMENTS 849

Where one party wants to introduce evidence of a prior oral or written agreement that failed to appear in the newer written document, the parol evidence rule will apply because integration of the new document essentially “seals the deal.” 50 But before a court can apply the rule to determine the scope of an agreement, it must answer two questions about integration.

First, the court must determine whether the writing is integrated, 51 by looking to whether the parties “intended the writing [to act] as a final expression of the terms it contains, even if the writing was not intended as a complete and exclusive statement of all terms” of the agreement.

52

No bright-line rule governs the determination of integration, which will be ascertained based on the parties’ actions and the writing itself.

53 Parties often include an integration clause in the document as a signal of integration.

54 Of course, mere insertion of the clause does not ensure

50. See Restatement (Second) of Contracts § 213 (1981) (describing application of rule). Integration renders the contract exclusive; no new terms may be added.

Subsequent agreements, however, do not fall under the rule’s prohibition. Scott & Kraus, supra note 46, at 561; see also John E. Murray, Jr., The Parol Evidence Rule: A

Clarification, 4 Duq. L. Rev. 337, 337 (1966) (declaring article dedicated to “clarification” of “fog” surrounding the Parol Evidence Rule). Murray explains that in situations where both agreements were oral, or a written agreement preceded the later oral agreement, the court would follow the “usual fashion” of trying to determine the “total agreement” of the parties. Id. at 338. The parol evidence rule only comes into play where the written agreement is latest in time: “When the parties to a contract embody the terms of their agreement in a writing, intending that writing to be the final expression of their agreement, the terms of the writing may not be contradicted by evidence of any prior agreement.” Id. at 337; see also Farnsworth, supra note 44, § 7.3, at 418–20 (discussing

Restatement provisions that forbid extrinsic evidence from modifying completely integrated agreement’s terms).

51. See Restatement (Second) of Contracts § 209(3) (defining integrated agreements); see also Farnsworth, supra note 44, § 7.3, at 419 (describing first question as

“is the agreement integrated?”).

52. Farnsworth, supra note 44, § 7.3, at 419.

53. Id. at 418–19. At common law, the “four corners” rule carried a presumption of full integration if the agreement appeared complete on its face. Scott & Kraus, supra note

46, at 542. The common law “natural omission” doctrine complemented this presumption by deeming a written contract integrated, and the alleged additional promise unenforceable, if the additional promise were so related to the subject covered by the writing that the “most natural” place for the alleged additional agreement to be found would have been “in the contract.” Mitchill v. Lath, 160 N.E. 646, 647 (N.Y. 1928). The court explained that oral agreements are admissible only if they are collateral in nature, do not contradict express or implied provisions of the written agreement, and comprise an agreement ordinarily not expected to be embodied in writing. Id. The court in Mitchill found the alleged unwritten promise unenforceable, since it would naturally have been found in the integrated purchase agreement. Id. While most courts have moved away from a strict adherence to the four corners rule, many common law courts still turn to the natural omission test to determine integration. Scott & Kraus, supra note 46, at 542–43.

54. Farnsworth, supra note 44, § 7.3, at 423; see supra note 6 (providing example of integration clause in Mr. Al-Arian’s plea agreement, proclaiming itself to be the “entire agreement”); see also infra note 110 (providing example of clause that goes even further by disavowing any other prior agreements).

R

R

R

R

R

R

R

R

\\server05\productn\C\COL\110-3\COL303.txt

unknown Seq: 11 15-APR-10 8:24

850 COLUMBIA LAW REVIEW [Vol. 110:840 that a court will automatically find integration.

55 Since, however, the doctrine places strong emphasis on the intentions of parties, an integration clause gives a court a strong intent-based justification for determining the writing to be final.

56 While an integration clause might be useful, the court may look at other factors. In fact, the Restatement approach permits the use of extrinsic evidence to help a court determine whether an agreement is partially, completely, or not integrated at all.

57 If an agreement “appears in view of its thoroughness and specificity to embody a final agreement on the terms that it contains,” then it will be considered integrated with respect to those terms.

58

If a court declares the writing integrated, it must next determine whether it is completely or only partially integrated. The level of integration in a writing will depend on whether the parties intended the writing to cement all the terms of the final agreement (complete integration), 59 or whether some of the agreement terms failed to appear in the writing

(partial integration).

60 The distinction between the levels of integration might seem trivial, but it has a substantial effect on the role of extrinsic evidence in interpretation of the writing. If a court deems a contract to be integrated, whether completely or partially, “evidence of prior or contemporaneous agreements or negotiations is not admissible in evidence to contradict a term of the writing.” 61 In a partially integrated writing, however, such evidence may be used to supplement —but not to contradict—the agreement terms.

62 Complete integration means that a court

55. Farnsworth, supra note 44, § 7.3, at 423–24.

56. Id.

57. Restatement (Second) of Contracts § 209(3) & cmt. c, § 214 cmt. a (1981)

(determination of integration will be made “in accordance with all relevant evidence”). Of course, courts are not bound to follow the Restatement, and different, more restrictive approaches to determining integration exist (such as that used by a court employing the

“four corners” rule discussed supra note 53, which directs a court to look to the face of the writing alone to determine integration). On the other hand, the Uniform Commercial

Code offers a permissive approach that avoids a presumption of integration. See U.C.C.

§ 2-202 cmt. 1 (2004) (“Unless there is a final record, these alleged terms are provable as part of the agreement by relevant evidence from any credible source.”).

58. Farnsworth, supra note 44, § 7.3, at 420 (citing Intershoe v. Bankers Trust Co., 571

N.E.2d 641 (N.Y. 1991)). In fact, it does not necessarily have to be signed by the parties at all to be integrated. Id. (citing Tow v. Miners Mem’l Hosp. Ass’n, 305 F.2d 73 (4th Cir.

1962)).

59. See Restatement (Second) of Contracts § 209(1) (explaining that an integrated writing constitutes “final expression of one or more terms of an agreement”).

60. Farnsworth, supra note 44, § 7.3, at 418–19.

61. Restatement (Second) of Contracts § 215. While it cannot contradict the terms, however, evidence of the parties’ “course of performance, course of dealing, or usage of trade” can usually supplement or explain the terms in an integrated agreement. U.C.C. § 2-

202(1)(a).

62. Restatement (Second) of Contracts § 216(1) (“Evidence of consistent additional terms is admissible to supplement an integrated agreement unless the court finds that the agreement was completely integrated.”); see also id. § 216 cmt. b (“Terms of prior agreements are superseded to the extent that they are inconsistent with an integrated agreement, and evidence of them is not admissible to contradict a term of the

R

R

R

R

\\server05\productn\C\COL\110-3\COL303.txt

unknown Seq: 12 15-APR-10 8:24

2010] PAROL EVIDENCE AND PLEA AGREEMENTS 851 will not admit any extrinsic evidence of additional terms, even if those terms could be enforced in harmony with the written terms.

2.

The Rule in Action. — While these rules sound straightforward enough, not all courts follow the same path in determining the level of integration. Indeed, the outcome of a case can turn on the court’s determination of whether the agreement is fully or partially integrated, as illustrated by a comparison of two canonical parol evidence rule cases:

Mitchill v. Lath 63 and Masterson v. Sine .

64 In Mitchill v. Lath , the New York

Court of Appeals refused to enforce an oral promise made by the Laths in a sale of their farm to the Mitchills.

65 The purchase contract failed to mention the Laths’s oral promise to remove an icehouse from the land— in fact it failed to mention the offending icehouse at all.

66 An agreement to remove the icehouse would not necessarily have conflicted with the agreement to purchase, but it would not necessarily have fallen within the ambit of the original purchase either, since the buyers could have contracted for the removal of the icehouse in a separate agreement.

67

Therefore, the court refused to tack the additional terms on to those contained in the writing.

In Masterson , the California Supreme Court refused to follow New

York’s lead in looking solely at the face of the writing to determine integration. Instead, Justice Traynor adopted an intent-centric approach that found the agreement only partially integrated, since the alleged oral agreement could have been made apart from the writing.

68 Even though the Masterson court invoked the same rule as that in Mitchill , their divergent methods of determining the level of integration led to very different results.

Eric Posner has employed the labels “hard” and “soft” to differentiate the approaches courts can take in applying the parol evidence rule, or in their interpretation of terms.

69 Whereas the “hard” courts, such as integration.”). Furthermore, integration will not prevent a party from introducing evidence of a collateral agreement, which must be separate from the main agreement’s terms although the collateral agreement does not necessarily have to involve

“consideration distinct” from that in the main agreement. Farnsworth, supra note 44,

§ 7.3, at 424; see also Mitchill v. Lath, 160 N.E. 646, 647 (N.Y. 1928) (finding collateral oral agreement inadmissible because it was too “closely related to the subject dealt with in the written agreement” to be admissible).

63.

Mitchill , 160 N.E. 646.

64. 436 P.2d 561 (Cal. 1968).

65.

Mitchill , 160 N.E. at 647.

66. Id. at 646.

67. Marvin A. Chirelstein, Concepts and Case Analysis in the Law of Contracts 99 (5th ed. 2006).

68.

Masterson, 436 P.2d at 563–64 (listing “many cases where parol evidence was admitted ‘to prove the existence of a separate oral agreement as to any matter on which the document is silent and which is not inconsistent with its terms’—even though the instrument appeared to state a complete agreement”).

69. Eric A. Posner, The Parol Evidence Rule, the Plain Meaning Rule, and the

Principles of Contractual Interpretation, 146 U. Pa. L. Rev. 533, 535 (1998). Posner

R

\\server05\productn\C\COL\110-3\COL303.txt

unknown Seq: 13 15-APR-10 8:24

852 COLUMBIA LAW REVIEW [Vol. 110:840 that in Mitchill , look to the face of the agreement itself to establish completeness, “softer courts [like the one in Masterson ] declare a writing complete only if the extrinsic evidence supports that determination,” meaning that they will “generally admit all relevant extrinsic evidence, because any inconsistent extrinsic evidence suggests (however indirectly) that the contract is incomplete.” 70 Regardless of whether a court uses a hard or soft approach, extrinsic evidence may come in under certain circumstances. As we have seen, the rule does not ban agreements that are “collateral,” or outside the scope of the integrated agreement.

71 Additionally, since the rule focuses on prior or contemporaneous agreements that did not make the final cut, it will not prevent a party from using extrinsic evidence to prove that there was no agreement, or that it was invalid in the first place.

72 For example, to show that the “writing was a forgery, joke, or sham,” a party may rely on written or oral representations or statements from prior negotiations.

73 Thus, the rule does not block the introduction of such evidence in the face of claims of unilateral or mutual misunderstanding, mistake, duress, misrepresentation, or fraud.

74

3.

The Purpose of the Rule. — Even though the practical applications and outcomes might vary among courts, the rationale behind the rule remains the same: to ensure that “[i]f the parties to a transaction express agreement and subsequently express another agreement, intending the subsequent agreement to prevail over their antecedent expression, their final expression will prevail.” 75 It might have started out as a rule of evidence, but the rule’s purpose has evolved since it was first established in

1604.

76 While modern day courts today still give “special protection” to pointed to Samuel Williston as the “chief defender” of the hard approach, and identified

Arthur Corbin as a champion of the soft approach. Id. at 568–71.

70. Id. at 535.

71. The rule ultimately aims to ascertain whether “the parties intend[ed] the subsequent written agreement to be their final and complete or ‘integrated’ expression, or . . . [if] they intend[ed] any prior agreements (oral or written) to be part of their total agreement.” Murray, supra note 50, at 338–40. A prior agreement on a collateral issue could be viewed as supplementing a partially integrated agreement. Since it would not contradict the terms of the agreement, it would not run afoul of the rule. See discussion supra notes 61–62 (noting terms that do not contradict may supplement terms of integrated agreement).

72. Farnsworth, supra note 44, § 7.3, at 426 (“[I]t does not exclude evidence to show that there was no agreement or that the agreement was invalid.”).

73. Id. § 7.4, at 427.

74. Id. § 7.4, at 429 (citing Restatement (Second) of Contracts § 214 (1981))

(explaining that the rule “does not exclude evidence to show mistake, misrepresentation, or duress as a ground for avoidance”).

75. Murray, supra note 50, at 338.

76. Countess of Rutland’s Case, (1604) 77 Eng. Rep. 89, 90 (K.B.) (holding contract

“made by writing, or by other matter as high or higher” would be controlled by final written agreement and refusing to consider oral “averments”). In refusing to consider prior oral or written agreements in the construction of the terms of deed, Chief Justice

Popham noted the fallibility of memory and the impropriety of allowing an oral statement

R

R

R

R

\\server05\productn\C\COL\110-3\COL303.txt

unknown Seq: 14 15-APR-10 8:24

2010] PAROL EVIDENCE AND PLEA AGREEMENTS 853 writings, 77 oral agreements engender less judicial suspicion today, and the rule’s more important purpose serves to assure the primacy of subsequent agreements over all prior promises or agreements, whether written or oral.

78 Like many other principles guiding contract interpretation, this function of the rule aims to provide predictability in enforcement.

79

The rule does not merely prevent a party from adding invisible or nonexistent terms to the agreement at a later date, 80 but also serves to promote trust in contracting, since the parties know at the outset what terms constitute the final agreement.

81 In addition, it serves to decrease plea agreement negotiation costs, and by promoting clarity the rule serves to decrease costs and time spent on litigation.

82 These goals, although born out of commerce, remain important when the parties bargain for a criminal conviction.

II. T

HE

D

OCTRINAL

M

ESS IN THE

F

EDERAL

C

IRCUITS

Although courts generally use tenets of private contract law to interpret their terms 83 and to fashion remedies, 84 plea agreements stand in a to trump a written contract—a “higher” form of agreement—holding that the most recent written document should control and negate any prior agreements. Id.

77. See Murray, supra note 50, at 338 (“When the prior expression is oral and the second is in writing, courts have traditionally followed a policy of affording special protection to the writing.”).

78. Farnsworth, supra note 44, § 7.2, at 416–18 (quoting Arthur L. Corbin, The Parol

Evidence Rule, 53 Yale L.J. 603, 607–08 (1944)). Farnsworth describes the purpose of the rule as giving parties the flexibility to make new agreements without worry that prior negotiations will hamper the enforceability.

79. Id.

80. See Arthur L. Corbin, The Interpretation of Words and the Parol Evidence Rule,

50 Cornell L.Q. 161, 189 (1965) (noting parol evidence rule renders prior oral or written agreements “inoperative by having been discharged by a subsequent agreement that has been duly proved and interpreted”).

81. See Scott & Kraus, supra note 46, at 541.

82. Id. Decreasing negotiation costs seems especially useful in a high stakes plea bargain, where negotiation costs and distrust could otherwise thwart an agreement.

83. See United States v. Barnes, 83 F.3d 934, 938 (7th Cir. 1996) (“Plea agreements are governed by ordinary contract principles.”); United States v. Kelly, 18 F.3d 612, 616

(8th Cir. 1994) (“When a dispute later arises over whether the parties performed pursuant to the agreed-upon terms, the court looks to familiar contract principles and gives effect to the intent of the parties as expressed in the plain language of the agreement when viewed as a whole.”); United States v. Ingram, 979 F.2d 1179, 1184 (7th Cir. 1992) (“Plea agreements are contracts, and their content and meaning are determined according to ordinary contract principles.”); United States v. Harvey, 791 F.2d 294, 300 (4th Cir. 1986)

(declaring courts generally draw on body of law “pertaining to the formation and interpretation of commercial contracts” in construction of plea agreement terms); see also

United States v. Moscahlaidis, 868 F.2d 1357, 1361 (3d Cir. 1989) (“Although a plea agreement occurs in a criminal context, it remains contractual in nature and is to be analyzed under contract-law standards.”); Henry v. Gov’t of V.I., 340 F. Supp. 2d 583, 586

(D.V.I. 2004) (citing Santobello v. New York, 404 U.S. 257 (1971), for proposition that

“court must resort to contract law in interpreting the agreement or in determining whether a breach occurred”); Scott & Stuntz, supra note 10, at 1910 (“[C]ourts . . . have

R

R

R

R

\\server05\productn\C\COL\110-3\COL303.txt

unknown Seq: 15 15-APR-10 8:24

854 COLUMBIA LAW REVIEW [Vol. 110:840 class apart from commercial contracts for obvious reasons.

85 The liberty interests at stake infuse interpretation of plea bargains with concerns for fundamental rights and fairness; courts should not only consider contract principles, but also ensure that the plea bargaining process is “attended by safeguards to insure the defendant [receives] what is reasonably due in the circumstances.” 86 In light of these concerns, should courts cabin the terms in an integrated plea agreement within the four corners of the document? Or should courts allow additional or external evidence when a defendant 87 alleges that an additional or prior agreement was made that does not appear in the terms of the agreement itself?

88

The federal circuit courts of appeals lack a consensus as to the proper role of the parol evidence rule and extrinsic evidence in the interpretation of plea agreement terms. While some improperly construe the doctrinal confusion as a circuit split, 89 a more fitting label might be a mess. The parol evidence rule, which delineates the terms, officially operates apart from rules of interpretation, which give meaning to those terms. Nonetheless, courts often add to the popular conflation of the two by invoking parol evidence rule precedent to support exclusion of extrinsic evidence in interpretation of terms.

90 And courts never mention the proceeded to construct a body of contract-based law to regulate the plea bargaining process . . . .”).

84. See United States v. Alexander, 869 F.2d 91, 95 (2d Cir. 1989) (“Although

Santobello does not use the term ‘contract’ when referring to a plea agreement, the remedies that it adopts for the government’s breach of a plea agreement are rescission and specific performance—both traditional contract remedies.”).

85. United States v. Herrera, 928 F.2d 769, 773 (6th Cir. 1991) (“Although the plea agreement is contractual in nature, it is by no means an ordinary contract.”); see

Moscahlaidis , 868 F.2d at 1361 (“Courts should consider not only ordinary contract principles but also ensure that the plea bargaining process is ‘attended by safeguards . . . .’ ” (quoting Santobello , 404 U.S. at 262)).

86.

Santobello , 404 U.S. at 262. As the Court pointed out in Boykin v. Alabama, 395

U.S. 238, 242 (1969), a guilty plea “is more than a confession which admits that the accused did various acts; it is itself a conviction; nothing remains but to give judgment and determine punishment.”

87. The government will likely never have reason to bring such a claim to a court.

88. Some defendants raise this issue as part of a pro se habeas petition requesting withdrawal of a plea because of an alleged breach of the agreement. Kingsley v. United

States, 968 F.2d 109, 115 (1st Cir. 1992); United States v. Garcia, 956 F.2d 41, 42–44 (4th

Cir. 1992). Alternatively, it might be raised as part of an appeal after sentencing. See, e.g.,

United States v. Swinehart , 614 F.2d 853, 856–57 (3d Cir. 1980). In Swinehart , under a discretionary “fairness and justice” standard, the trial court could withdraw a plea and order a trial if it seemed “fair and just.” Id. at 857 (internal quotation marks omitted).

Normally, “[w]hether the government has violated a plea, or by analogy, a cooperation agreement, is a question of law subject to de novo review.” United States v. Baird, 218 F.3d

221, 229 (3d Cir. 2000).

89. Petition for Writ of Certiorari at 10, Al-Arian v. United States, No. 08-137 (U.S.

July 30, 2008), cert. denied, 129 S. Ct. 288 (2008).

90. It is confusing enough that parol evidence is generally banned (by the parol evidence rule) in determining the scope of an agreement’s terms, as well as in determining the meaning of the terms (by interpretation principles), but courts often go further. Take,

\\server05\productn\C\COL\110-3\COL303.txt

unknown Seq: 16 15-APR-10 8:24

2010] PAROL EVIDENCE AND PLEA AGREEMENTS 855 level of integration, if they do mention integration of a writing at all.

91

Finally, the line between scope and interpretation does not always remain clear in decisions. For example, the doctrinal lines might blur when a defendant claims that the agreement’s ambiguous language should be read in light of a claimed prior oral agreement.

92 For purposes of case for example, a case where the meaning of terms were in dispute and the defendant sought to introduce evidence of statements made in negotiations.

Swinehart, 614 F.2d at 856–57.

The question is better understood as one of interpretation, not scope (which is what the parol evidence operates to define). But right before the court allowed extrinsic evidence from negotiations to “shed light on the meaning of a pertinent word or phrase,” it declared that the “parol evidence rule should not be rigidly applied to bar evidence . . . [from assisting in] properly construing the plea agreement.” Id. at 858 (emphasis added)

(quoting Wilson Arlington Co. v. Prudential Ins. Co. of Am., 912 F.2d 366, 370 (9th Cir.

1990)). In addition, a court dealing with an interpretation issue might also cite the parol evidence rule to support its decision. United States v. Nunez, 223 F.3d 956, 958 (9th Cir.

2000) (responding to defendant’s argument that terms were ambiguous by citing parol evidence rule, which it confusingly construed as preventing use of “ ‘extrinsic evidence . . .

to interpret . . . the terms of an unambiguous written instrument’ ”). For example, in

Raulerson v. United States , the court found that “even the most liberal reading of the supplemental plea agreement fails to support the interpretation that Mr. Raulerson urge[d].” 901 F.2d 1009, 1012 (11th Cir. 1990). The “interpretation” Raulerson urged was actually a verbal agreement not included in the text of his plea. Id.

91. Moreover, the determination of integration here is usually far simpler than the complex two-step process discussed supra Part I.B. Without referring to the Restatement’s nuanced, contextual approach, courts here point to the integration clause and declare it integrated. See, e.g., United States v. Alegria, 192 F.3d 179, 186 (1st Cir. 1999) (declaring that “the integration clause . . . withstands the appellant’s bombardment” and thus Alegria could not “seek the benefit of a prior oral representation by the government after he signed a fully integrated writing that did not contain the claimed representation”); cf.

United States v. Rockwell Int’l Corp., 124 F.3d 1194, 1200 (10th Cir. 1997) (specifically finding complete integration). More often, however, courts will skip the inquiry into integration status, simply using the presence of the integration clause itself as a proxy for complete integration. See United States v. Al-Arian, 514 F.3d 1184, 1192 (11th Cir. 2008)

(per curiam) (finding that integration clause proves that “plea agreement reflects all of the promises and agreements between Al-Arian and the government”). “Notwithstanding the integration clause, Al–Arian argue[d]” that evidence from negotiations should be allowed to inform a reading of the agreement. Id. The court rejected this argument. Id. (citing

United States v. Altro (In re Altro), 180 F.3d 372 (2d Cir. 1999)). The importance of the integration or merger clause here seems to lie in its disavowal of prior or other agreements. Id. However, a court might also dismiss such “boilerplate language” in the face of strong evidence of an agreement.

Baird , 218 F.3d at 230 (“This obvious boilerplate does not contain language purporting to supersede the December 9 letter.”); United States v. Melton 930 F.2d 1096, 1098–99 (5th Cir. 1991) (similar result). Additionally, while neither of those cases mentions partial integration, it would seem to explain their dismissal of the effects of the integration clause, as the proposed additional terms did not directly conflict with anything in the agreement.

92. In re Arnett, 804 F.2d 1200, 1203 (11th Cir. 1986). In a few other cases, courts have confusingly discussed whether or not they should “interpret” an agreement’s terms or silences in light of a claimed prior agreement or negotiations. See United States v. Cantu,

225 F. App’x 301, 301 (5th Cir. 2007) (rejecting defendant’s claims of “oral promises outside of the plea agreement” while citing Ballis for proposition that “parol evidence is inadmissible to prove the meaning of an unambiguous plea agreement” (internal quotation marks omitted) (quoting United States v. Ballis, 28 F.3d 1399, 1410 (5th Cir.

\\server05\productn\C\COL\110-3\COL303.txt

unknown Seq: 17 15-APR-10 8:24

856 COLUMBIA LAW REVIEW [Vol. 110:840 analysis, this Note follows the courts in lumping together the questions and doctrine concerning an agreement’s scope and meaning (both of which carry a ban on outside evidence) under the umbrella of a general parol evidence ban on “modification” of contract terms by extrinsic evidence.

Most courts tend to uphold enforcement of the terms of plea agreements with integration clauses, ignoring or disallowing external evidence of other agreements. However, these cases—especially those that find for the defendant—often contain language suggesting that the special constitutional concerns at issue in plea bargaining give room for leeway in allowing the use of parol evidence to aid in interpretation of terms, resulting in a certain unpredictability of outcomes based on doctrine alone.

93

The Fourth, Eleventh, and Seventh Circuits, however, follow a different path, allowing parol evidence only under exceptions, and placing more focus on whether evidence of government overreaching exists.

94

Part II.A discusses the “classic” doctrinal approach, the more traditional ban on parol evidence imposed by the majority of the circuits. Although decided using similar rules, these cases do not always turn out the same, 95 bringing to mind the earlier discussion of commercial cases, which often turn on whether the court uses a hard or soft application of the parol evidence rule.

96 Part II.B goes on to discuss what this Note terms the “overreaching approach” used by the Fourth, Seventh, and

Eleventh Circuits, which departs from the traditional parol evidence ban by allowing extrinsic evidence only when there is evidence of government overreaching or ambiguity in the writing.

A.

The Majority of the Circuits Follow the “Classic Approach” to Parol Evidence

When a plea agreement contains an integration clause declaring the agreement to be the final and controlling declaration of the parties’ intentions, the Second, Fifth, Sixth, and Tenth Circuits have all declined to admit evidence of competing or omitted terms. As any hornbook will tell you, this is the standard procedure in the interpretation of all contracts.

97

Even in circuits with a proclaimed allegiance to the black letter law ap-

1994)); Swinehart , 614 F.2d at 858 (“[E]vidence of a prior draft plea agreement, or of statements made by the prosecution during the plea bargaining which sheds light on the meaning of a pertinent word or phrase in an ‘integrated’ plea agreement would be admissible.”).

93. See infra part II.A (discussing doctrinal approaches and their results).

94. See infra part II.B (discussing overreaching approach).

95. The difference in outcomes does not always depend on sympathetic facts. In the

Third Circuit, for example, defendants have won on mere claims of oral agreements, even without affidavits from attorneys or written documentation to support their claim. See infra notes 117, 122 (discussing such cases).

96. See supra notes 69–70 and accompanying text (differentiating between hard and soft application of parol evidence rule).

97. Farnsworth, supra note 44, § 7.2, at 415.

R

R

R

\\server05\productn\C\COL\110-3\COL303.txt

unknown Seq: 18 15-APR-10 8:24

2010] PAROL EVIDENCE AND PLEA AGREEMENTS 857 proach, the special plea agreement context concerns interact with the court’s decision to employ a hard or soft parol evidence ban, and can result in different outcomes despite the similarity in doctrine. Part II.A.1

describes standard applications of contract principles blocking introduction of parol evidence, while Part II.A.2 explores opinions that use the same doctrinal rule peppered with special concerns for defendants in this context.

1.

No Extrinsic Evidence Allowed. — The Fifth Circuit has held that parol evidence of a defendant’s understanding of his obligations under a plea agreement during negotiations to be irrelevant, as “parol evidence is inadmissible to prove the meaning of an unambiguous plea agreement.” 98 Ballis claimed that the parties had reached an agreement as to the repercussions if he failed to cooperate, but nothing in the plea itself spoke to remedies, and the court felt that a “lack of comprehensive provisions specifying remedies in the case of breach does not render the agreement ambiguous, as Ballis claimed.

99 This case, although cited often in the Fifth Circuit thanks to its quotable summary of the doctrine, almost does not qualify as a parol evidence case, since the defendant did not present any evidence of a prior or conflicting agreement.

100 In fact, the court seemed to use the parol evidence rule as a shorthand way of concluding that in fact no prior agreements existed, but that if they did, it would not matter because Ballis’s actions in violating the agreement smacked of unfair play, contrary to regular contracting principles.

101

United States v. Rockwell International Corp.

involved allegations of a prior additional agreement much more explicitly than Ballis . In Rockwell , the corporate defendant pleaded guilty to several environmental crimes in exchange for assurances that the government would refrain from “fur-

98. United States v. Ballis, 28 F.3d 1399, 1410 (5th Cir. 1994) (“Although circumstances surrounding the agreement’s negotiations might indicate that such was

Ballis’ intent, parol evidence is inadmissible to prove the meaning of an unambiguous plea agreement.”).

99. Id. (“There is nothing in the agreement suggesting . . . that the government had agreed that prosecuting Ballis for perjury was its exclusive remedy for a breach of the agreement.”).

100. In a later unpublished case, the Fifth Circuit cited Ballis for the proposition that despite what evidence about agreements from negotiations might show, it could not be admitted to aid in interpretation of an unambiguous plea agreement. United States v.

Cantu, 225 F. App’x 301, 301 (5th Cir. 2007) (citing Ballis , 28 F.3d at 1410). But then, perhaps just to assure readers, the court noted that parol evidence rule aside, “nothing in the record [supported Cantu’s] assertion that the Government made oral promises outside of the plea agreement and later breached those promises.” Id.

101. The court finally held that in failing to meet the conditions of the plea, Ballis had “fraudulently induced his original plea agreement,” and therefore lost his right to enforcement of the terms.

Ballis , 28 F.3d at 1411. In reality, the court might not have even reached the parol evidence issue, and still would have been able to uphold rescission of the agreement on those grounds. Indeed, the paragraph dealing with the parol evidence rule begins as a hypothetical, since the court felt that Ballis’s fraudulent inducement of the agreement renders it void anyway. Id. at 1410 (“Moreover, even were the agreement enforceable, Ballis’ obligations under it were not ambiguous.”).

\\server05\productn\C\COL\110-3\COL303.txt

unknown Seq: 19 15-APR-10 8:24

858 COLUMBIA LAW REVIEW [Vol. 110:840 ther criminal and, to a lesser extent, civil proceedings,” and later advocated an interpretation of the agreement that would prevent the government from intervening in a qui tam action against the defendant.

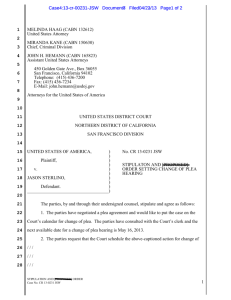

102 In construing a plea agreement the court “applie[d] a two-step process in interpreting the terms of a plea bargain: first, the court examine[d] the nature of the government’s promise; second, the court investigate[d] this promise based upon the defendant’s reasonable understanding at the time the guilty plea was entered.” 103 In support of its position, the defendant attempted to present correspondence with the government and transcripts of testimony to support its proposed interpretation of the plea agreement.

104 The court, however, held that the proposed parol evidence was not admissible as evidence of an additional term modifying what it found to be a completely integrated plea agreement.

105 The integration clause in the agreement “severely limited” inquiry into the defendant’s “reasonable understanding at the time it entered its guilty plea.” 106

The court rejected the defendant’s “interpretation,” noting that “[w]hat

Rockwell really seeks is to add a term to the agreement,” 107 which it found to be blocked by the parol evidence rule.

108

The Second Circuit has followed a similar course, holding in United

States v. Altro ( In re Altro ) that, particularly where “the Government incorporates into the plea agreement an integration clause expressly disavowing the existence of any understandings other than those set forth in the plea agreement, a defendant may not rely on a purported implicit understanding in order to demonstrate that the Government is in breach.” 109

There, the defendant argued that a subsequent subpoena breached the implicit pact underlying his plea agreement, despite an integration clause.

110 The defendant claimed that he was under the impression he

102. United States v. Rockwell Int’l Corp., 124 F.3d 1194, 1196 (10th Cir. 1997).

103. Id. at 1199 (citing Cunningham v. Diesslin, 92 F.3d 1054, 1059 (10th Cir. 1996)).

104. Id. at 1198.

105. Id at 1199–200. The Rockwell court did one of the most thorough integration analyses out of all the cases discussed. It found complete integration after looking to the integration clause, noting that the parties did not dispute its integration, citing the

Restatement (Second) of Contracts for the proposition that “a writing that appears integrated will be considered as such.” Id. (citing Restatement (Second) of Contracts

§ 209(3) (1981)).

106. Id. at 1199.

107. Id. at 1200 (“Regardless of whether Rockwell’s extrinsic evidence vindicates its assertion that the government agreed to be so limited in intervening in the Stone Suit, the parol evidence rule forbids Rockwell from asserting this additional term.”). This opinion does a nice job of highlighting the overlap between scope and the interpretation of an agreement’s terms.

108. The court both laid out a summary of the parol evidence rule and cited the

Restatement (Second) of Contracts in its exposition of the rule. Id. at 1199 (citing

Restatement (Second) of Contracts §§ 215–216).

109. United States v. Altro (In re Altro), 180 F.3d 372, 376 (2d Cir. 1999).

110. Id. at 375. The integration clause stated in relevant part, “this Agreement supersedes any prior understandings, promises, or conditions between this Office and

Ralph Altro. No additional understandings, promises, or conditions have been entered

\\server05\productn\C\COL\110-3\COL303.txt

unknown Seq: 20 15-APR-10 8:24

2010] PAROL EVIDENCE AND PLEA AGREEMENTS 859 would not be forced to testify again later because of the nature of the plea negotiations, and because the government had not informed him that he could be forced to do so.

111

Like the Tenth Circuit in Rockwell , the Second Circuit read the plea’s silence on the matter as foreclosing any arguments of an additional agreement.

112 Similarly, the Altro court also rejected the defendant’s argument for a more lax application of the parol evidence rule, noting that the record held no written evidence of a statement by the government.

113

Altro offers an example of the inherent contradiction built into the soft approach to the parol evidence rule: a court declares the importance of the parol evidence rule while simultaneously appearing to weigh the evidence in the record to support its decision to exclude such evidence.

114

The above cases all disallow using parol evidence of outside or prior agreements during plea negotiations to augment or interpret plea terms.

Some courts, however, tend to employ the same doctrine, only to reach different results through a softer application.

2.

No Extrinsic Evidence Allowed, Unless . . . . — Sometimes, cases will cite the same basic doctrine as the courts above, but hold that given the special nature of a plea agreement, the parol evidence may be allowed, despite the integration of an agreement. One might expect that compelling facts or ambiguity in the interpretation of a contract would prompt judges to search outside the four corners for meaning, but some cases appear to take a softer approach, frequently looking to the extrinsic evidence to determine integration in the first place, and more often coming into other than those set forth in this Agreement, and none will be entered into unless in writing and signed by all parties.” Id. at 373.

111. Id. at 375.

112. Id. at 376 (“We decline to require the Government to anticipate and expressly disavow every potential term that a defendant might believe to be implicit in such an agreement.”).

113. Id. The court distinguished these facts from United States v. Garcia, 956 F.2d 41

(4th Cir. 1992). See infra notes 141–148 and accompanying text (discussing Garcia ). The

Altro court, like the Fifth Circuit in United States v. Cantu, 225 F. App’x 301 (5th Cir.

2007), also turned to the record to reinforce its decision declaring the importance of the parol evidence rule, illustrating one of the classic contradictions within this doctrine. See supra note 100 (discussing Cantu ). It concluded that “in appropriate circumstances we might consider relaxing the parol evidence rule in order to hold the Government” to its promise, but “there was, in this instance, no promise for us to enforce.” Altro , 180 F.3d at

376; cf. United States v. Aleman, 286 F.3d 86, 91 (2d Cir. 2002) (holding that, in dispute over immunity agreement terms, while “a district court need not conduct a hearing every time a defendant summarily accuses the government of failing to live up to an alleged bargain, . . . here [defendant] submitted an affirmation from his attorney and appeared to offer other corroborating evidence in the form of other attorneys’ affidavits”).

114. See supra notes 69–74 and accompanying text (discussing seeming paradox in soft approaches that look to extrinsic evidence before declaring whether or not contract is integrated); see also infra notes 141–150 and accompanying text (discussing “fraud in the inducement”). Although the core of Altro depends on the hard approach, it appears that the court simply offered the soft approach (pointing to the lack of evidence of an agreement) as a backup argument.

R

R

R

R

\\server05\productn\C\COL\110-3\COL303.txt

unknown Seq: 21 15-APR-10 8:24

860 COLUMBIA LAW REVIEW [Vol. 110:840 out in favor of the defendant.

115 Additionally, the language in these opinions evokes more sympathy for defendants, often stressing the special liberty concerns. This section discusses the few cases, all from the

First and Third Circuits, in which a defendant won simply by claiming an additional oral agreement, 116 as opposed to producing documentary evidence of a government promise. These cases hint that something inherent in the nature of a plea agreement—something beyond a mere ambiguity in the terms—prompts courts to tread softly when banning such evidence and to construe the doctrine to allow extrinsic evidence.

The Third Circuit has not been afraid to uphold an alleged prior agreement, especially when it exists in written form, by reading it in tandem with later agreements that remain silent on the matter:

Reading the formal plea agreement against the government as the drafter, and in light of its acceptance of the plea to obstruction of justice as an apparent cure of the initial breach, [the court found] that the government treated the [prior] agreement as remaining in effect. That conclusion is not altered by the plea agreement’s integration clause, which states that “no additional promises, agreements or conditions have been entered into other than those set forth in this document . . . .”

This obvious boilerplate does not contain language purporting to supersede the [previous] letter. Further, the two documents may be read consistently with one another. In light of these

115. In particular, the First and Third Circuits alone saw the only two parol evidence cases in which a defendant won with claims of a mere oral agreement that did not make its way into the text, without backing from affidavits from attorneys. This is not to say, however, that defendants routinely triumph in First Circuit cases. See United States v.