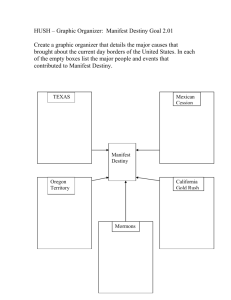

Manifest Destiny's Legacy

advertisement