don't put a cork in granholm v. heald: new york's ban on interstate

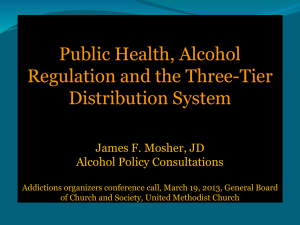

advertisement