to view this Comment - American University Law Review

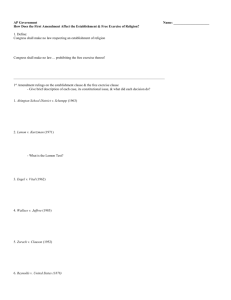

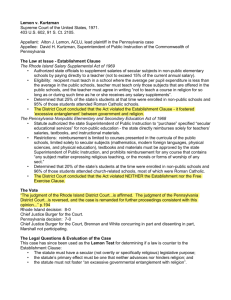

advertisement