cultural differences in self-serving behaviour

advertisement

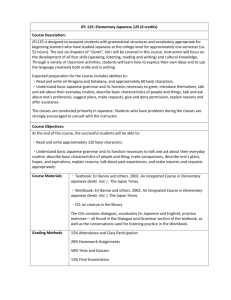

CULTURAL DIFFERENCES IN SELF-SERVING BEHAVIOUR IN ACCOUNTING NARRATIVES ABSTRACT In the letter to the shareholders management renders account of the activities in the preceding year by providing explanations for the results and, frequently, looks forward to the next year. These are the stories that narrate the successes and failures of individuals (e.g., the CEOs), organisational subunits, and the entire company. Attribution theory hypothesises on the bias in these stories and expects management to be self-serving by attributing positive developments to themselves and negative developments to the environment. Indeed, this so-called “self-serving attributional bias”, though originating from social psychology, has also been shown in the context of organisational outcomes including the letter to the shareholders of Western companies. Recent social psychological research on this self-serving attributional bias, however, has revealed that there are cultural differences in these attributional patterns. More specifically, this cross-cultural research revealed that the self-serving bias is typically found in western, individualistic cultures, but is to a lesser extent present in eastern, collectivistic cultures. Therefore, in line with these findings one would expect this self-serving attributional bias to be more prevalent in annual reports of companies from individualistic countries than those from collectivistic countries. In this paper we will report some results based upon a study of letters to the shareholders of American and Japanese companies. Keywords: culture, accounting narratives, international financial accounting. CULTURAL DIFFERENCES IN SELF-SERVING BEHAVIOUR IN ACCOUNTING NARRATIVES INTRODUCTION In the CEO’s letter to the shareholder management renders account of the company’s activities of the preceding fiscal year by providing explanations for the obtained results. These are the stories that narrate the successes of the individuals (e.g., the CEO), organisational subunits, and the entire company (Fiol, 1989). It is not inconceivable that the board will use this opportunity to interpret events to its own benefit (Hines, 1988; Ginzel, Kramer, and Sutton, 1993), also because the annual report seems to be a public relations instrument aimed at nurturing a certain corporate image (Hopwood, 1996). For example, Preston, Wright, and Young (1996) suggested that annual reports are designed to send the right message, i.e., to enhance the story of corporate performance contained in the financial statements or to signal or, maybe more likely, to detract attention away from poor performance. Indeed, historical data from large UK corporations seem to confirm that “corporate executives use annual reports as part of an image management function to influence external stakeholders” (Lee, 1994: 215). Research shows that the explanations offered by individuals (and groups as well) are self-serving: individuals are willing to take credit for successful outcomes, but are reluctant to take responsibility for unsuccessful outcomes. This so-called “self-serving attributional bias”, though originating from social psychology, has also been shown in the context of organisational outcomes (Johns, 1999) including the letter to the shareholders. The research mainly focused on the United States (Bettman and Weitz, 1983; Staw, McKechnie, and Puffer, 1983; Salancik and Meindl, 1984; D’Aveni and MacMillan, 1990; Clapham and Schwenk, 1991), with a notable exception of Belgium (Aerts, 1994). In general these studies showed that self-serving behaviour is also present found in annual reports, although Aerts only found Belgian companies claiming successful results. Recent research within social psychology, however, suggests that the explanations that people provide for events may depend upon their cultural background and that, as a consequence, the self-serving attributional bias is less universal or robust as it was thought to be. Indeed, some social scientists suggested that the self-serving attributional bias might be more typical for western societies than for eastern societies (Choi and Nisbett, 1998; Choi, Nisbett, and Norenzayan, 1999; Menon, Morris, Chiu, and Hong, 1999). Furthermore, Gray’s (1988) theory and its recent validations seem to suggest that financial reporting to a certain extent is a reflection of a nation’s cultural background (for an excellent recent overview see Chanchani and MacGregor, 1999). Therefore, the central research question of this paper is whether such a cultural difference may also be found in explanatory behaviour in annual reports. It presents some preliminary findings based on a study of annual reports of American and Japanese companies. The remainder of the paper is organised as follows. In the second paragraph, attention is paid to the theoretical background when studying explanatory behaviour in annual reports in general, while also some previous research, mainly using data from the Eighties and focussing on western nations, are briefly addressed. The third paragraph covers some of the recent findings within social psychology indicating that the self-serving attributional bias may be less profound in eastern nations. It also tries 2 to provide possible reasons for this divergence. The fourth paragraph contains the propositions that will be tested in this paper and, in addition, describes the research method used. Paragraph five contains some of the preliminary results of this study. The paper ends with a short discussion and conclusion section. ATTRIBUTION THEORY AND IMPRESSION MANAGEMENT Attribution theory provides the basis for studying explanatory behaviour in annual reports. It consists of a number of social psychological ideas that focus on perceived causality, i.e., people’s ideas about causes of events. The work of social psychologist as Heider (1958) and Weiner (1971, 1985, 1986) resulted in a taxonomy that can be used to study the explanations people offer. Frequently, a two-dimensional taxonomy is used consisting of “locus of causality” (indicating whether a cause is internal or external to the person) on the one hand and “stability” (indicating whether a cause is temporal or might persist over time) on the other. Using this taxonomy, researchers were able to reveal certain tendencies in people’s explanatory behaviour, not only in experimental settings but also under more natural conditions, e.g., newspaper stories. People are “self-enhancing” if it involves successful outcomes, implying that they will take credit for it by saying that they were personally responsible for the outcome. However, if it involves unsuccessful outcomes, i.e., failures, people show “selfprotecting” tendencies, implying that the environment or something beyond their control, e.g., bad luck, is held responsible for the outcome. These tendencies have also been studied and shown in organisational contexts in general (Johns, 1999), including accounting narratives as indicated previously. In the mid-Eighties and early-Nineties several American researchers, predominantly from the organisational domain, applied these social psychological ideas to annual reports. The studies of Bettman and Weitz (1983), Staw, McKechnie, and Puffer (1983), Salancik and Meindl (1984), D’Aveni and MacMillan (1990), and Clapham and Schwenk (1991) indicated that managers are very alike ordinary people: they are, generally speaking, inclined to take credit for positive results, e.g., an increase in profits or sales, while negative outcomes are blamed onto the environment. Apart from using such acclaiming (e.g., enhancements) and accounting tactics (e.g., excuses and justifications), managers also are able to obfuscate possible reasons for an outcome. Aerts (1994) suggested that a cause-effect relation might be expressed in accounting-technical terms, e.g., “profits declined as results of an increase of the financial costs”. What is typical of such an explanation is that it remains unclear whom is responsible for the outcome and that it is open to multiple interpretation. In a sense, these accounting explanations are used to avoid the need of giving explanations. Given these characteristics, it is no surprise that Aerts’ study revealed that managers show a preference to explain negative outcomes in accounting-technical terminology, whereas positive outcomes are explained more in clear-cut causal language where responsibility may be easily assigned. In a sense, this accounting bias and the self-serving tendency can be seen as complementary. Firms show a preference for using self-enhancing claims when explaining positive performance, while they prefer to use technical-accounting language to account for negative performances – thereby hoping that their responsibility for the failure is mystified (Aerts, 1991, 1994). By the use of such accounting, acclaiming and obfuscation tactics individuals attempt to control the impressions others form of them (Leary and Kowalski, 1990). Although people are not always aware of the impressions they convey, a certain strategic behaviour can be assumed. Indeed, the claim that impression management 3 is instrumental (Goffman, 1959; Schlenker and Weigold, 1992) or purposive, goaldirected behaviour (Bozeman and Kacmar, 1997) may be particularly true for organisations and their members. Within an agency theoretical setting the use of impression management, and self-serving explanatory behaviour in particular, may be expected beforehand. Managers, guided by their self-interests, will highlight the positive whereas as little attention as possible is paid to negative outcomes. Indeed, Abrahamson and Park (1994) refer to two important motives to use such a concealment strategy. Firstly, managers do not want others to become aware of such negative outcomes not only because this may affect their bonuses, but also because it may impinge on their reputations. Secondly, as disclosure of this kind of information usually leads shareholders to sell their share, this results in a decrease in firm’s value and may make it more vulnerable to a hostile take-over. The use of such impression management tactics seems especially important if a person’s behaviour is public (Leary, 1996). Indeed, Fiol (1995) revealed such a private-public effect in an organisational context. She compared managers’ attributions in external communication (i.e., the letter to the shareholders) with those in internal communication (i.e., internal planning documents). Using content analysis she found that managers’ private and public statements are not necessarily converging. She found that threats (i.e., negative, uncontrollable causes) are more frequently used in internal documents than in external documents, while in the case of opportunities (i.e., positive, controllable causes) more or less the opposite applies. Using a same line of argument, Aerts and Theunisse (2000) investigated whether listing status influenced attributional behaviour in accounting narratives. Using a recent sample of Belgian letters to the shareholders, they were able to show that listed companies are both more self-enhancing and self-protecting than non-public companies when explaining positive and negative accounting outcomes, respectively. However, there are limits to be overly self-serving. The impressions conveyed have to be credible: “self-serving tendencies can be effective as long as the message they represent is plausible and the messenger remains credible” (Aerts and Theunisse, 2000: 6). Credibility is one of the most crucial aspects of disclosure effectiveness (Gibbins et al., 1990). In addition, the financial report is generally speaking a publicly available document and is used by many constituencies in their decision-making process. These constituencies, such as, e.g., institutional investors, shareholders, employees, creditors, banks, et cetera, are expected to read the financial report carefully as well that they will confront it with information from other sources, e.g., their own knowledge, press releases, journal articles, and analysts’ forecasts. Because of this public scrutiny gross inaccuracies may be detected quickly (Bettman and Weitz, 1983). As these constituencies possess other information resources than the annual report as well, it may be possible that the explanations offered by the management, e.g., a considerable increase in profits due to good strategic policy, are viewed differently by them. So management always runs the risk that a part of their audiences may not accept its view of the events. CULTURAL DIFFERENCES IN SELF-SERVING BEHAVIOUR In the previous paragraph we discussed a tendency that both ordinary people and managers have: they prefer to claim positive outcomes, whereas negative outcomes are blamed onto the environment. Although people across cultures generally show a self-serving bias, research also indicates that there is a pervasive difference between western cultures (notably the United States) and eastern cultures (mostly Japan) (e.g., Kashima and Triandis, 1986; Morris and Peng, 1994; Smith and Bond, 1996; Lee and 4 Seligman, 1997; Semin and Zwier, 1997). All these studies, using different methods and subjects, arrived at the same, general conclusion: the self-serving bias was found more in western cultures than in eastern cultures. On the one hand, Americans are more than eastern subjects inclined to explain events in terms of dispositional factors, and typically when it involves successful outcomes implying that people from eastern cultures are more modest in the attributions they make. On the other hand, people in eastern cultures are more inclined to assume personal responsibility for a failure than Americans do: especially Japanese, but also Indian and Chinese, respondents showed a self-deprecating tendency. For example, Menon and her colleagues (1999) used actual newspaper stories related to business scandals to establish such cultural differences. One of the scandals involved the rogue trading by Nick Leeson leading to the collapse of Barings, Britain’s oldest bank. Comparison of the attributions made in an American newspaper (The New York Times) and in a comparable Japanese one (Asahi Shimbun), showed the same pattern as previous researchers found in experimental settings. They found that the American newspaper referred more frequently to the individual than the organisation as the cause of the financial scandal, the Japanese newspaper, on the other hand, referred more to the organisation as a possible cause. From the social psychological literature it seems that two interrelated aspects, viz. construal of the self and communication styles are used to explain differences in attributional patterns (e.g., Gudykunst and colleagues, 1986, 1996, 1997; Triandis, 1989, 1995; Markus and Kitayama, 1991, 1994; Kagitçibasi, 1997; Semin and Zwier, 1997). Both aspects are reflections of differences in individualism, i.e., differences in patterns of social relationships. In a collectivistic culture as Japan, social ties and groups are very important. In contrast, in an individualistic culture as the United States, the person as a separate entity is more important, while the ties between individuals are loose as well (e.g., Hofstede, 1984; Triandis, 1995). These differences are clearly present in the construal of the self, which defines how a person perceives him- or herself vis-à-vis another. Following Markus and Kitayama (1991, 1994) it is possible to make a distinction between the independent and the interdependent construal of the self. The independent construal dictates that a person is independent from others and an emphasis is on the expression of one’s unique attributes, and is typical for the individualistic, western cultures. In contrast, in the interdependent construal of the self, the person is regarded as not separate from the social context but as more connected to and less differentiated from others (Markus and Kitayama, 1991: 227). Evidently, this construal predominates in eastern, collectivistic cultures. Differences in the view of the self have implications for people’s verbal behaviours (Markus and Kitayama, 1991) and their definition of self-esteem (Markus and Kitayama, 1991, 1994; Nurmi, 1992; Heine and Lehman, 1997). As the focus in the independent view of the self is on one’s own person it is logical that outcomes are explained in dispositional terms (Cousins, 1989; Markus and Kitayama, 1991; Morris and Peng, 1994; Lee, Hallahan, and Herzog, 1996). In addition, self-esteem in individualistic countries requires that one’s uniqueness is stressed and that inner attributes are expressed (Markus and Kitayama, 1991, 1994). This will lead to selfenhancing behaviours. In collectivistic countries, on the other hand, the focus is on the social context in which one is operating. Therefore, situational or contextual attributions are expected. Besides, stimulating self-esteem is achieved in a different way than in individualistic countries. Markus and Kitayama (1991, 1994) note that positive feelings about the self should derive from fulfilling the tasks associated with being interdependent with relevant others: belonging, fitting in, occupying one’s proper place, engaging in appropriate action, promoting others’ goals, and 5 maintaining harmony. Hence, in these nations there is a “collective self-esteem” (Kagitçibasi, 1997; Crocker and Luhtanen, 1990). Therefore, it should not be surprising that self-enhancement or self-promotion are perceived negatively in the Japanese culture (Markus and Kitayama, 1991). In these cultures modesty is the norm reflecting the influence of Confucius (Heine, Takata, and Lehman, 2000). Indeed, Kitayama et al. (1997) and Akimonto and Sanbonmatsu (1999) argue that the fact that people in eastern societies are more sensitive to negative self-relevant information than people from western cultures, does not imply that they are low(er) in selfesteem. Rather, such a kind of behaviour has positive consequences in eastern cultures: it serves to affirm one’s belongingness to a group and can be seen as part of a strategy of self-improvement (Meijer and Semin, 1998: 17). Therefore, it may be argued that the modesty and self-deprecating tendency typically found in the Japanese culture is the result of a consideration of others. Otherwise stated, the Japanese seem to make sure not to deny others’ contribution to a success, and save their face by not blaming them in any way for a failure, also because blaming others would disrupt harmony in a relationship (Meijer and Semin, 1998: 15). Another related difference between the Americans and the Japanese involves differences in self-evaluations. Whereas the Americans are more prone to information regarding their positive characteristics, the Japanese have a more self-critical orientation (Heine, Lehman, Markus, and Kitayama, 1999 and Heine et al., 2000). According to, e.g., Heine et al. (2000) the main reason for such a focus on one’s weaknesses is the continue urge for self-improvement among the Japanese. The second factor that may explain the differences in the amount of the selfserving attributional bias concerns the communication style. Hall (1977) proposed that the context is important in understanding the messages people convey and that the importance of the context varies across cultures. He distinguished high-context and low-context communication cultures, although admitting that each culture has elements of both. Following Hall (1977: 91) a high-context communication or message is one in which most of the information is either in the psychical context or internalised in the person, while very little is in the coded, explicit part of the message. Zwier (1998) characterises this high-context style as indirect, implicit, and affective (see also Gudykunst et al., 1996). A low-context communication is according to Hall (1977: 91) just the opposite; i.e., the mass of the information is vested in the explicit code. Therefore, it can be characterised as a direct, explicit and instrumental communication style (Zwier, 1998; Gudykunst et al., 1996). Following Gudykunst and Ting-Toomey (1988) and Singelis and Brown (1995) it appears that in individualistic countries, e.g., the United States and most of north-western Europe the use of low-context communication styles predominates. In collectivistic countries, e.g., Japan, southern European and Latin American countries, however, the highcontext communication style is more apparent. Ehrenhaus (1983) related Hall’s variations in context to attributional styles. He argued that members in high-context cultures are attributionally sensitive and predisposed toward situational features and situationally based explanations. Members of low-context cultures, on the other hand, are attributionally sensitive to and predisposed towards dispositional characteristics and dispositionally based explanations (1983: 263). In addition it also seems that in a high-context culture, e.g., Japan, people in high positions are more prepared to accept responsibility for a failure than similar people from low-context cultures, such as the United States and the Netherlands (Hall, 1977). In the latter case frequently a low(er)-ranked scapegoat is offered: Oliver North in the contra’s-Iran scandal is only one famous example underscoring this. Finally, Triandis (1994: 184-185) also points to several important differences in communication styles between individualistic (or 6 low-context) and collectivistic (or high-context) cultures. First, in individualistic cultures the focus is on the communicator, also evidenced by the fact that the word “I” is used frequently. In these cultures, attributes as credibility, intelligence, and expert knowledge are important. On the other hand, in collectivistic cultures, the focus to a larger extent is on the receiver. In addition, the word “we”, stressing interdependency, is also emphasised, whereas ambiguity, subjectivity, generality, and vagueness in communication is also more common. This could indicate that the use of accounting-technical language (Aerts, 1991, 1994) would be even more prevalent in these cultures than it is in an individualistic culture such as Belgium. PROPOSITIONS AND RESEARCH DESIGN As indicated in the introduction the primary aim of this paper is to explore whether there is a cultural difference in annual reports regarding the explanations offered in the CEO’s letter to the shareholders. Notwithstanding the exploratory mode of this paper, we derived the following propositions based upon the review of the literature. P1 Both Japanese as well as American companies will show a self-serving tendency to explain organisational results in their letters to the shareholders, although this tendency is stronger in the United States than in Japan. P2 Japanese companies will ascribe positive outcomes (e.g., an increase in profits) to causes external to the organisation to a larger extent than American companies in the letter to the shareholders (“modesty tendency”). P3 Japanese companies are more inclined to accept blame for a negative outcome (e.g., a loss or decreasing profits) by ascribing it to internal causes than American companies (“self-deprecating tendency” or self-criticism). P4 The use of accounting-technical language to explain organisational outcomes is more prevalent in Japanese letters to the shareholders (a high communication-context culture) than in those from the United States (a low communication-context culture). In this study we focused on large companies from the United States and Japan. Three reasons justify this choice. First, and foremost, these countries represent cultures with significant differences with regard to the individualism-collectivism dimension, which constitute the most important factor influencing cultural differences in attributional behaviour as previous research has indicated. Second, previous studies within social psychology indicating such a cultural difference also predominantly focused on these two countries. Lastly, the United States and Japan are economically important countries, both in terms of representation of companies in, e.g., the Fortune Global 500, as well as in terms of size of the stock market. The selection of the companies from these countries was based on the 1999 Fortune Global 500 list, resulting in 30 companies from the United States and Japan (the appendix provides a list of the companies included). Because of their specific nature, we excluded financial companies beforehand. Of the companies included in our study we used the most recent annual report. In large part the US companies had a year-end of 31 December 1999, whereas the Japanese companies predominantly had a year-end of 31 March 1999. All the reports included in this study were in English, also for the Japanese companies. A survey distributed among investor relations department of 70 large Japanese companies (selected from the Fortune 7 Global 500), to which 26 companies responded revealed that 19 or 73% distributed an English annual report only among investors. In order to be able to provide answers to the propositions posited earlier and as we are dealing with narrative statements in annual reports we used content analysis, which is a research method that uses a set of procedures to make valid inferences from text (Weber, 1990: 9). This technique was also used in related studies by Aerts (1991, 1994, 1996), Bettman and Weitz (1983), Clapham and Schwenk (1991), Salancik and Meindl (1984), and Staw et al. (1983) (see Jones and Shoemaker (1994) for an overview of the application of content analysis in accounting). The objective of content analysis here is to establish in what way directors explain organisational performances in the letter to the shareholder. Hence, basically we are interested in “causal statements”. A causal statement or attribution refers to one or more coherent sentences or phrases (i.e., part of sentence) in which an organisational outcome (i.e., profits, sales, revenues, etc.) is connected with a cause or reason (“explanatory variable”) for that outcome. Causal statements may be related to past/present or future organisational outcomes. The fiscal year under consideration is the point of reference for deciding on past/present outcomes. Frequently, a causal statement may be recognised explicitly because connective words or phrases are used, for example: “influenced by”, “is caused by”, “contributed to”, “can be ascribed to”, “because”, “despite”, “notwithstanding”, and so on. However, a sentence or phrase is considered a causal statement as well if no such connective words or phrases are present, but a causal relationship between an organisational outcome and explanatory variable can implicitly be derived from the text. To be considered a causal statement, a cause-effect relationship has to be clearly present. Furthermore, organisational outcome (“effect”) and explanatory variable (“cause”) have to appear in proximity, e.g., within one or two sentences, or within the same paragraph. Whenever several causes or reasons (“explanatory variable”) are provided to explain one organisational outcome, whether or not in the same sentence, each of those combinations are treated as a separate causal statement. The identified causal statements are then coded along a number of dimensions, including the following. 1. Valence of effect, indicating whether the outcome explained is to be evaluated positive (e.g., increase in sales, decrease in loss et cetera) or negative (e.g., decrease in sales, increase in profits et cetera) from the directors’ point of view. 2. Locus of causality, which aims to measure whether a cause is internal (e.g., due to corporate strategy, other management’s decisions, quality of personnel et cetera) or is external and beyond management’s control (e.g., general economic conditions, inflation, interest, a natural disaster, et cetera). 3. Direction of cause-effect relationship, revealing whether cause and effect have the same sign (e.g., increase in profits due to a well established corporate strategy) or have opposite signs (e.g., despite the Asia Crisis we were able to increase our sales). 4. Language of causal statement, a dimension aimed at measuring whether the causeeffect relationship is expressed in clear-cut causal language or in accountingtechnical language. An example of the latter is that profits rose as a consequence of decreasing financial costs. 20% of the letters to the shareholders were independently coded by two coders. As can be seen in table I the intercoder reliability, as expressed by the correlation coefficients, is reasonably high and comparable to previous studies. 8 Take in Table I RESULTS Table II below contains descriptive data relating to the general financial characteristics of the Japanese and American companies included in the sample. Regarding average sales no statistical significant difference is found. The American companies, however, had on average a significant larger net income to report (p = 0,000). In that respect, the American companies experienced a better year than those from Japan did. Data obtained from the Worldscope database reveals that the Japanese companies included in our study had a net income decline of approximately 64,64% to report, reflecting among others the Asia Crisis. Nevertheless, still 9 of the Japanese companies could report a positive growth in net income. With respect to sales a similar picture emerge: overall they reported a contraction of sales by 6,48%. The American companies included in our study, on the other hand, had good performances to report: overall sales increased by 15,21%, while net income rose by 17,51% (21 American companies reported an increase in net income). Take in Table II Although the American CEOs had, comparatively speaking, good news to report they produced only slightly larger letters to the shareholders than their Japanese counterparts did when measured in number of pages (p = 0,075). However, when measured in terms of standardised lines the Americans did have larger letters (p = 0,003): on average their letters counted 126,97 lines, while the Japanese letters only had 96,66 lines (see table III below). Take in Table III Despite that the Americans, on average, produced somewhat larger letters to the shareholders than the Japanese CEOs did, no difference was found regarding the number of causal statements contained in the letters. On average the letters to the shareholders contained 6 to 7 causal statements each. This figure is quite comparable to the Salancik and Meindl (1984) and the Clapham and Schwenk (1991) studies, in which on average 8,5 and 7, respectively causal statement per letter were found. It is larger than the number found in the Bettman and Weitz' study (1983), who on average found 2,3 causal statements per letter. However, in this study only explicit, easily identifiable statements were included. Furthermore, the Japanese CEOs addressed less organisational outcomes in their letters than their colleagues from the United States did: 2,43 and 3,53, for Japan and U.S. respectively, although this difference was not significant. This slightly more extensive explanatory behaviour by the Japanese, both in terms of number of causal attributions and number of reasons to explain one organisational outcome, is in line with previous social psychological research which suggested that, especially unexpected, negative outcomes arouse the search for causal explanations (e.g., Schlenker, 1980; Weiner, 1986). It is also in line with the previous attributional research on letters to the shareholders (Bettman and 9 Weitz, 1983; Salancik and Meindl, 1984). It seems that CEOs want to give the appearance of being in control by providing reasons for the poor performance. In good times, a good strategy seems to let the results speak for themselves to a certain extent. Table IV presents an indication of the difference between in the countries regarding the valence of the explained effects. In line with the negative performance trend that the Japanese companies experienced, 65,3% of the causal attributions had a negative valence from the CEO's or company's point of view. The Americans on the other hand had mostly positive outcomes to report: only 14,4% of the causal attributions had a negative valence. This difference in valence of evaluated effects between the United States and Japan is statistically significant (χ2 = 93,55 and p = 0,000). Take in Table IV Table V presents the average scores regarding the ascription of positive and negative outcomes to internal or external causes for the whole sample, without taking into account the relative trend in profits. Using a non-parametric test (MannWhitney), we found the U.S. companies claiming positive results to a larger extent than their Japanese counterparts did. Indeed, the Japanese ascribed almost half of the total amount of positive effects to factors beyond their control. Take in Table V The Japanese CEO's, on the other hand, who on average had to account for declining profits, were more willing to assume personal responsibility for this relative failure than their American colleagues. However, they also blamed the environment to a larger extent than the CEO's from the United States did. These findings, and particularly those concerning IP and IN provide some indication that there is a difference in explanatory behaviour between American and Japanese CEOs. More specifically, the results seem to support proposition 2 and indicate that Japanese CEOs are more modest in the ascription of positive outcomes than their American colleagues, i.e., also include the environment as a cause. In addition, although the Japanese also lay blame on the environment for the losses incurred, they also accept blame for them to a larger extent than the American CEOs did. On average, the Japanese CEOs mentioned a internal cause 4 times as much as the Americans to explain a decline in net income. Therefore, these results also seem to support proposition 3, indicating that the Japanese are more self-deprecating than the Americans. In order to measure self-serving tendencies we compared the average number of evaluated effects ascribed to internal versus external causes. Self-enhancing of positive outcomes implies more taking credit than involving the environment as a possible cause, i.e., IP - EP > 0. Self-protection is just the opposite with respect to negative outcomes, i.e. EN - IN > 0, implying that people are more likely to blame the environment for a failure than to assume personal responsibility for it. Below (table VI) the data to establish these tendencies in the United States and Japan are presented. 10 Take in Table VI On average the CEOs from the United States show self-enhancing tendencies (i.e., IP - EP > 0): they claim successes by ascribing them to causes internal to the organisation, e.g., a well-established strategy, good management, etc. The Japanese, on the other hand, show self-protecting tendencies (EN - IN > 0): on average, they blamed the environment, e.g., the Asia Crisis, the low exchange rate of yen to the US dollar, etc., for the deterioration in performance they experienced. Furthermore, a Mann-Whitney test reveals that the for the whole sample, the Americans are more self-enhancing than the Japanese (Mann-Whitney U= 183,500 and p-value = 0,000), whereas the Japanese are more self-protecting (Mann-Whitney U = 297,000 and pvalue = 0,016) than the Americans. These results seem logical given the difference in performance (in terms of net income) between the two countries: on average, the Americans had to account for successes, whereas the Japanese had to explain failures. In addition, we also performed separate tests to compare the behaviours of profitable and unprofitable American and Japanese firms (i.e., those experiencing a positive and negative income growth, respectively); see table VII below. Take in Table VII The results are comparable to the whole sample: both the profitable and unprofitable American firms showed self-enhancing tendencies, whereas no self-protecting tendencies were noticeable. The Japanese, on the other hand, irrespective of performance showed self-protecting tendencies, but we could not find any selfenhancing tendencies. Furthermore, although the Japanese attributed positive effects more to the environment and are more willing to accept blame for failures than the American CEOs in the case of both profitable and unprofitable firms, this difference was statistically not significant (except for unprofitable Japanese CEOs accepting more blame for negative outcomes than their American colleagues). Given these differences in performances reported, the results seem to support proposition 1: both American and Japanese companies show self-serving tendencies in their letter to the shareholders. In this study we also looked at more subtle ways of impression management. More specifically we studied whether we could discover variations in language use in the letters to the shareholders between the two nations. First of all we looked at the length of causal statements concerning positive and negative outcomes respectively. In a recent study of UK letters to the shareholders Clatworthy and Jones (1998) tested whether managers of 50 profitable and 50 unprofitable companies used differential reporting strategies with regard to good and bad news. Their results showed that companies prefer to stress good news: both profitable and unprofitable firms devoted more space to good news than to bad news. In our study we also investigated whether the amount of space devoted to good news is larger than that devoted to bad news in both Japan and the United States. The length was measured in two ways: not only did we count the number of words, in addition we also measured the length by using a uniform grid, i.e., a transparent A4-sheet divided into 400 boxes of equal size. The results are presented in table VIII. The American 11 companies on average used a balanced coverage strategy: we could not find a significant difference in the amount of space devoted to good or bad news. A similar result was obtained by Bettman and Weitz (1983) in their study of American letters to the shareholders: they were neither able to find any main effects. This is quite different from the results of the Clatworthy and Jones (1998) study. Possible explanations for this divergence might be that we focused on causal statements sec and used sentences (from one punctuation to another) to measure the amount of space, whereas in the Clatworthy and Jones study the individual positive or negative words were used to measure the amount of space. Furthermore, the items included as good or bad news in the Clatworthy and Jones study were broader than our study, as we only included causal statements regarding accounting outcomes and shareholder value. Take in Table VIII The Japanese companies that reported a positive growth in net income used a similar coverage strategy as their American counterparts did: the amount of space devoted in the letter to the shareholders to good and bad news is balanced (i.e., no statistically significant difference could be found). The Japanese companies that experienced a bad year, on the other hand, particularly seemed to feel the need of providing explanations for this results: both in terms of words and boxes the amount of space devoted to bad news was larger than that devoted to good news. This finding is in line with previous social psychological research which suggests that the amount of causal reasoning will be more extensive if outcomes are unfavourable and/or unexpected (Weiner, 1986). Furthermore, we also looked at the way causal statements are expressed: either in clear-cut causal language or in accounting-technical language where responsibility may not easily be assigned. The results are presented in table IX. Take in Table IX Although in both the American and Japanese letters to the shareholders accountingtechnical language is used more frequently to explain negative outcomes than to explain positive outcomes, this difference is statistically not significant. However, it seems that the use of accounting-technical language is more prevalent in Japan than in the United States (χ2 = 3,477 and p = 0,052) and particularly to explain positive effects. Regarding negative effects we could not find any significant difference in language use between the two countries (χ2 = 0,316). Overall, i.e., when not taking into account the valence of the explained effects, the results support proposition 4: the Japanese used accounting-explanations to a larger extent than the Americans did to explain organisational outcomes (χ2 = 5,994 and p-value = 0,010). We also checked for the presence of the so-called accounting bias implying that positive outcomes are accounted for in causal language, while negative outcomes are more accounted for in accounting-technical language (see, Aerts, 1994). Take in Table X 12 Table X indicates that in both the United States as well as in Japan positive outcomes are predominantly accounted for in causal language as is in line with Aerts' findings. However, contrary to his results, we find that negative outcomes are also explained in causal language, indicating that the CEOs of both countries are not inclined to conceal the reasons for a decline in sales, income etc. by using such accounting explanations. Furthermore, we also looked at the direction of the cause-effect relationship (see table IX). Variations in directions may be used as subtle impression management techniques: in order to leverage or highlight a certain effect, e.g., "Notwithstanding the Asia Crisis out net income rose to 4,035 billion". Because of this characteristic the use of such form of impression management seems particularly logical to explain positive outcomes, but not to explain negative outcomes. In the letters to the shareholders we examined, such leverage was mostly used to account for positive outcomes as expected (US: χ2 = 2,779 and p = 0,087; Japan: χ2 = 6,694 and p = 0,009). Furthermore, it seems that the Japanese used it to a larger extent than the Americans to explain negative outcomes. These outcomes may be seen a further indication of the self-deprecating tendencies of the Japanese people. DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION In this paper we investigated the CEO’s letter to the shareholders of 30 large American and Japanese companies. The main purpose of this study was to examine possible variations in attributions of positive and negative organisational outcomes as a function of different cultural backgrounds between the two countries. We predicted, in line with the social psychological research, that both Japanese and American CEOs will show self-serving tendencies when explaining outcomes in their letters to the shareholders. Furthermore, it was also hypothesised that when compared to the American CEOs, the Japanese CEOs would be more modest in attributing positive outcomes, i.e., also are inclined to ascribe them to external causes, and more self-deprecating with regard to negative outcomes, i.e., accept blame by ascribing them to internal causes. The attributional patterns found in the letters studied to a large extent supported these propositions. Both the American and the Japanese CEOs show self-serving tendencies: on average, the Americans ascribed the positive outcomes they experienced to their own efforts (i.e., causes internal to the organisation). The Japanese, who on average had to account for declining profits, showed a self-protecting tendency: they blamed the environment, e.g., the Asia Crisis, for the bad results. However, they were also more modest in the attribution of positive results than the Americans: they referred to external factors as possible causes to a larger extent. However, somewhat more surprisingly, they leveraged positive outcomes also to a larger extent, thereby somewhat weakening their modesty. Regarding negative outcomes, the Japanese CEOs are very alike the ordinary people: they show a strong self-deprecating tendency. Compared to their American colleagues they not only referred to internal factors as causes more often, in addition they leveraged the negative outcomes by using opposite directions between cause and effect (e.g., despite the expanding economies of the United States and in Europe, we reported a net loss of 5,389 billion). Furthermore, we also looked at the language used to explain positive and negative outcomes. Aerts (1994) hypothesised and found that Belgian firms prefer to explain negative outcomes in ambiguous accountingtechnical language in which responsibility is not really addressed, whereas positive 13 outcomes were explained in more clear-cut causal language. In our study, however, we did not find such a bias: both positive and negative outcomes are explained in causal language. However, our study did reveal a cultural difference: as expected, the Japanese used accounting technical language to a larger extent than the American CEOs. In sum, the results found in this study largely concur with those found in earlier social psychological research: CEOs are like ordinary people and show the same tendencies. REFERENCES Abrahamson, E. and C. Park (1994). “Concealment of negative organisational outcomes: An agency theory perspective.” Academy of management journal, vol. 31: 1302-1334. Aerts, W. (1991). “Rekenschap en legitimatie. Studie van het publiek gebruik van boekhoudkundige informatie in een verhalende context.” Academic PhD-Thesis RUFA. Antwerp. Aerts, W. (1994). “On the use of accounting logic as an explanatory category in narrative accounting disclosures.” Accounting, organisations and society, vol. 19: 337353. Aerts, W. (1996). “Inertia in corporate explanation patterns and annual reporting.” Working paper RUCA/Departement toepgepaste economische wetenschappen 96/18. Aerts, W. and H. Theunisse (2000). “Listing status of the firm as motivational factor for attributional search in annual reporting”. Paper presented at the 23rd EAA Congres, Munich. Akimoto, S. A. and D. M. Sanbonmatsu (1999). “Differences in self-effacing behaviour between European and Japanese Americans.” Journal of cross-cultural psychology, vol. 30:: 159-177. Bettman, J. R. and B. A. Weitz (1983). “Attributions in the board room: Causal reasoning in corporate annual reports.” Administrative science quarterly, vol. 28: 165-183. Bozeman, D. P. and K. M. Kacmar (1997). “A cybernetic model of impression management processes in organisations.” Organisational behaviour and human decision processes, vol. 69: 9-30. Chanchani, S. and A. MacGregor (1999). “A synthesis of cultural studies in accounting”. Journal of accounting literature, vol. 18: 1-30. Choi, I. and R. E. Nisbett (1998). “Situational salience and cultural differences in the correspondence bias and actor-observer bias.” Personality and social psychology bulletin, vol. 24: 949-960. Choi, I., R. E. Nisbett, and A. Norenzayan (1999). “Causal attribution across cultures: Variation and universality.” Psychological bulletin, vol. 125: 47-63. Clapham, S. E. and C. R. Schwenk (1991). “Self-serving attributions, managerial cognition, and company performance.” Strategic management journal, vol. 12: 219229. Clatworthy, M. and M. J. Jones (1999). “The reporting strategies of profitable and unprofitable accounting narratives: Some preliminary findings.” Unpublished working paper, Cardiff Business School. Courtis, J. K. (1998). “Annual report readability variability: Tests of the obfuscation hypothesis.” Accounting, auditing and accountability journal, vol. 11: 459-471. Cousins, S. D. (1989). “Culture and self-perception in Japan and the United States.” Journal of personality and social psychology, vol. 56: 124-131. 14 Crocker, J. and R. Luhtanen (1990). “Collective self-esteem and ingroup bias.” Journal personality and social psychology, vol. 58: 60-67. D’Aveni, R. A. and I. C. MacMillan (1990). “Crisis and the content of managerial communications: A study of the focus of attention of top managers in surviving and failing firms.” Administrative science quarterly, vol. 35: 634-657. Ehrenhaus, P. (1983). “Culture and the attribution process.” In W. B. Gudykunst (ed.), Intercultural communication theory. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage. Fiol, C. M. (1989). “A semiotic analysis of corporate language: Organisational boundaries and joint venturing.” Administrative science quarterly, vol. 34: 277-303. Fiol, C. M. (1995). “Corporate communications: Comparing executive’s private and public statements.” Academy of management journal, vol. 38: 522-536. Gibbins, M., A. Richardson, and J. Waterhouse. “The management of corporate financial disclosure: Opportunism, ritualism, policies, and processes”, Journal of accounting research, vol. 28: 121-143. Goffman, E. (1959). “The presentation of self in everyday life.” New York: Anchor Books. Gray, S.J. (1988). “Towards a theory of cultural influence on the development of accounting systems internationally.” Abacus, vol. 24: 1-15. Gudykunst, W. B. (1997). “Cultural variability in communication: An introduction.” Communication research, vol. 24: 327-348. Gudykunst, W. B., Y. Matsumoto, S. Ting-Toomey et al. (1996). “The influence of cultural individualism-collectivism, self construals, and individual values on communication styles across cultures.” Human communication research, vol. 22: 510543. Gudykunst, W. B. and T. Nishida (1986). “Attributional confidence in low- and highcontext cultures.” Human communication research, vol. 12: 525-549. Gudykunst, W. B. and S. Ting-Toomey (1988). “Culture and interpersonal communication.” Newbury Park, CA: Sage. Hall, E. T. (1977). “Beyond culture.” New York: Achor Books. Heider, F. (1958). “The psychology of interpersonal relations.” New York: John Wiley & Sons. Heine, S. J. and Lehman, D. R. (1997). “The cultural construction of selfenhancement: An examination of group-serving biases.” Journal of personality and social psychology, vol. 72: 1268-1283. Heine, S.J., D.R. Lehman, H.R. Markus, and S. Kitayama (1999). “Is there a universal need for positive self-regard?”, Psychological review, vol. 106: 766-794. Heine, S.J., T. Takata, and D.R. Lehman (2000). “Beyond self-presentation: Evidence for self-criticism among Japanese.” Personality and social psychology bulletin, vol. 26: 71-78. Hines, R. D. (1988). “Financial accounting: In communicating reality, we construct reality.” Accounting, organisations and society, vol. 13: 251-261. Hofstede, G. (1980). “Culture’s consequences: International differences in workrelated values.” Beverly Hills, CA: Sage. Hofstede, G. (1984). “Cultural dimensions in management and planning.” Asia Pacific journal of management, vol. ??: 81-99. Hopwood, A. G. (1996). “Making visible and the construction of visibilities: Shifting agendas in the design of the corporate report: An introduction.” Accounting, organisations and society, vol. 21: 54-56. Johns, G. (1999). “A multi-level theory of self-serving behaviour in and by organisations.” In B. M. Staw and R. I. Sutton (eds.), Research in organisational behaviour, vol. 21. Greenwich, Connecticut: JAI Press. 15 Jones, M. J. and P. A. Shoemaker (1994). “Accounting narratives: A review of empirical studies of content and readability.” Journal of accounting literature, vol. 13: 142-184. Kagitçibasi, C. (1997). “Individualism and collectivism.” In J. W. Berry et al. (eds.), Handbook of cross-cultural psychology, Volume 3: Social behaviour and applications. Boston: Allyn and Bacon. Kashima, Y. and H. C. Triandis (1986). “The self-serving bias in attributions as a coping strategy: A cross-cultural study.” Journal of cross-cultural psychology, vol. 17: 83-97. Kitayama, S., Markus, H. R., Matsumoto, H., and Norasakkunkit, V. (1997). “Individual and collective processes in the construction of the self: Selfenhancement in the United States and self-criticism in Japan.” Journal of personality and social psychology, vol. 72: 1245-1267. Leary, M. R. (1996). “Self-presentation: Impression management and interpersonal behaviour.” Boulder, COL: Westview Press. Leary, M. R. and R. M. Kowalski (1990). “Impression management: A literature review and two-component model.” Psychological bulletin, vol. 107: 34-47. Lee, F., M. Hallahan, and T. Herzog (1996). “Explaining real-life events: How culture and domain shape explanations.” Personality and social psychology bulletin, vol. 22: 732-741. Lee, T. (1994). “The changing form of the corporate annual report”. The accounting historians journal, vol. 21: 215-232. Lee, Y. T. and M. E. P. Seligman (1997). “Are Americans more optimistic than the Chinese?” Personality and social psychology bulletin, vol. 23: 32-40. Markus, H. R. and S. Kitayama (1991). “Culture and the self: Implications for cognition, emotion and motivation.” Psychological review, vol. 98: 224-253. Markus, H. R. and S. Kitayama (1994). “The cultural construction of self and emotion: Implications for social behaviour.” In S. Kitayama and H. R. Markus (eds.), Emotion and culture: Empirical studies of mutual influence. Washington: APA. Markus, H. R., S. Kitayama, and R. J. Heiman (1996). “Culture and “basic” psychological principles.” In E. T. Higgins and A. W. Kruglanski (eds.), Social psychology: Handbook of basic principles, New York: Guilford Press. Meijer, Z. Y. and G. R. Semin (1998). “When the self-serving bias does not serve the self: Attributions of success and failure in cultural perspective.” Working paper Free University Amsterdam. Menon, T., M. W. Morris, C. Chiu, and Y. Hong (1999). “Culture and construal of agency: Attribution to individual versus group dispositions.” Journal of personality and social psychology, vol. 76: 701-717. Morris, M. W. and K. Peng (1994). “Culture and cause: American and Chinese attributions for social and physical events.” Journal of personality and social psychology, vol. 67: 949-971. Nurmi, J. (1992). “Cross-cultural differences in self-serving bias: Responses to the attributional style questionnaire by American and Finnish students.” The journal of social psychology, vol. 132: 69-76. Preston. A. M., C. Wright, and J. J. Young (1996). “Imag[in]ing annual reports.” Accounting, organisations and society, vol. 21: 113-137. Salancik, G. R. and J. R. Meindl (1984). “Corporate attributions as strategic illusions of management control.” Administrative science quarterly, vol. 29: 238-254. Schlenker, B.R. (1980). “Impression management: The self-concept, social identity, and interpersonal relations.” Montery, CA: Brooks/Cole Publishing Company. 16 Schlenker, B. R. and M. F. Weigold (1992). “Interpersonal processes involving impression regulation and management.” Annual review of psychology, vol. 43: 133168. Semin, G. R. and S. M. Zwier (1997). “Social cognition.” In J. W. Berry et al. (eds.), Handbook of cross-cultural psychology, Volume 3: Social behaviour and applications. Boston, MA, Allyn and Bacon. Singelis, T. M. and W. J. Brown (1995). “Culture, self, and collectivist communication: Linking culture to individual behaviour.” Human communication research, vol. 21: 354- 389. Staw, B. M., P. I. McKechnie, S. M. Puffer (1983). “The justification of organisational performance.” Administrative science quarterly, vol. 28: 582-600. Triandis, H. C. (1989). “The self and social behaviour in differing cultural contexts.” Psychological review, vol. 96: 502-520. Triandis, H. C. (1994). “Culture and social behaviour.” New York: McGraw-Hill. Triandis, H. C. (1995). “Individualism and collectivism.” Boulder: Westview. Weber, R. P. (1990). “Basic content analysis.” Newbury Park, CA: Sage. Weiner, B. (1985). “An attributional theory of achievement motivation and emotion.” Psychological review, vol. 92: 548-573. Weiner, B. (1986). “An attributional theory of achievement motivation and emotion.” New York: Springer Verlag. Weiner, B., I. Frieze, A. Kukla, L. Reed, S. Rest, and R. M. Rosenbaum (1971). “Perceiving the causes of success and failure.” Morristown: General learning press. Zwier, S. M. and G. R. Semin (1997). “Culturele verschillen in zelfpresentatie.” Fundamentele sociale psychologie, vol. 11: 135-149. Zwier, S. M. (1998). “Patterns of language use in individualistic and collectivistic cultures.” Ph.D. Thesis, Free University Amsterdam. 17 APPENDIX: COMPANIES EXAMINED US General Motors Wal-Mart Exxon General Electric Ford Motors Philip Morris Compaq Boeing IBM At&T Hewlett Packard K-Mart Procter&Gamble DuPont BellAtlantic HomeDepot Lucent Technologies Sears, Roebeck & Co. Intel Corp. Chevron Merck SBC Com. JC Penney Kroger Lockheed Motorola Texaco USPS GTE UTC Japan Mitsui Itochu Toyota Marubeni Sumitomo Nissho Iwai Hitachi Matsushita Sony Nissan Honda Mitsubishi Electric Nippon Steel Bridgestone Fujitsu NEC Canon Jusco Mazda Sharp Suzuki Fuji Film DDI Japan Airlines DNP Kobe Steel Asahi Glass Toppan Toshiba Mitsubishi Corporation 18 TABLES Table I Intercoder reliability of data Correlation coefficient Valence 1,000 Locus 0,895 Direction 0,767 Language 0,386 p-value (one-tailed test) 0,000 0,000 0,000 0,011 Table II General financial characteristics # Average sales (in th USD) Average net income (in th USD) Sales growth (%)# Net income growth (%)# U.S. companies 60.108.767 Japanese companies 45.835.805 4.001.883 137.995 15,21% 17,51% (6,48%) (64,64%) In the case of Japan the growth % is based on JPY figures Table III Descriptive data regarding letters to the shareholders U.S. Companies Average length in number 3,93 (2,05)** of pages Average length in number 126,97 (69,28) * of lines divided by number of columns per page Average number of causal 5,50 (5,69) statements in letter Average number of 3,53 (3,45) explained effects in letter Average number of 3,13 (4,09) explanations per outcome Japanese companies 3,43 (1,36) 96,66 (30,40) 6,53 (4,02) 2,43 (2,88) 4,43 (3,35) ** , * represent significant differences between means of U.S. and Japanese companies at the 10% and 1% levels respectively in two tailed t-tests. The numbers between brackets represent the standard deviations. 19 Table IV Crosstabulation Country * Valence explained effect Valence explained effect Positive Negative Number % Number % United States 137 85,6% 23 14,4% Japan 68 34,7% 128 65,3% Total 205 57,6% 151 42,4% Table V Descriptive data regarding causal statements American companies (n=30) Mean Sd % # Japanese companies (n=30) Mean Sd % Internal, positive (IP) External, positive (EP) 3,30 0,63 2,98 1,56 83,90% 16,10% 1,00# 0,77 1,64 1,04 56,60% 43,40% Internal, negative (IN) External negative (EN) 0,20 0,47 0,61 1,14 31,58% 68,42% 0,90# 2,43# 1,03 2,31 27,00% 73,00% Difference between United States and Japan is statistically significant at the 1% level Table VI Self-serving tendencies in American and Japanese letters to the shareholders Mean Sd Z-value p-value United States (n=30) IP – EP (self-enhancement) 2,6667 2,8567 -4,3788# 0,0000 EN – IN (self-protection) 0,2667 1,3629 -0,6325 0,5271 # Japan (n=30) IP – EP (self-enhancement) EN – IN (self-protection) 0,2333 1,5333 1,5687 2,4738 -1,0000 -3,5301# 0,3173 0,0004 Effect is statistically significant at the 1% level using a (non-parametric) binomial test with testproportion = 0,50 20 Table VII Self-serving tendencies for profitable and unprofitable companies Profitable companies Unprofitable companies (Us = 21;Japan = 9) (Us =9; Japan = 21) Mean Sd Mean Sd IP Us 3,67 3,20 2,44# 2,35 Japan 1,89 2,20 0,62 1,20 p = 0,149 p = 0,021 EP Us 0,81 1,83 0,22 0,44 Japan 1,22 1,20 0,57 0,93 p = 0,106 p = 0,416 EN US 0,62# 1,32 0,11@ 0,33 Japan 1,44 0,88 2,86 2,61 p = 0,017 p = 0,001 IN US 0,14 0,65 0,33* 0,50 Japan 0,44 1,01 1,10 1,00 p = 0,164 p = 0,049 #φ @α IP-EP US 3,10 2,28 2,86 2,22 Japan 0,67 2,40 0,05 1,07 p = 0,028 p = 0,005 EN-IN Us 0,48 1,54 -0,22# 0,67 α φ Japan 1,73 0,60 1,00 2,74 p = 0,164 p = 0,040 @ Difference between US and Japan is statistically significant at the 1% level using a Mann Whitney test; Difference between US and Japan is statistically significant at the 5% level using a Mann Whitney test; * Difference between US and Japan is statistically significant at the 10% level using a Mann Whitney test; p p-value refers to significance of difference between US and Japan as calculated in a Mann Whitney test; φ Effect is statistical significant at the 1% level using a binomial test (test proportion = 0,5000); α Effect is statistical significant at the 5% level using a binomial test (test proportion = 0,5000). # Table VIII Good and bad news coverage in companies with positive and negative net income growth Good news Bad news (causal statement with (causal statement with positive valence) negative valence) Positive Negative Positive Negative growth growth growth growth American companies Mean total words 35,48 28,14 39,28 23,40 Mean total number of 10,75 10,52 11,44 8,40 boxes from grid Japanese companies Mean total words Mean total number of boxes from grid 28,20 9,00 28,48** 10,15* ** , * 26,86 9,28 36,30** 13,95* represent significant differences between means of "profitable" and "unprofitable" companies at the 5% and 1% levels, respectively in a two-tailed t-test 21 Table IX Crosstabulation with regard to variation in type of language Type of Leverage/Direction of Cause-efffect relationship Cause-effect relationship Accounting Valence Causal technical language Same Opposite outcome language Positive 122 89,1% 15 10,9% 170 82,9% 15 10,9% U.S. n=30 Negative 19 82,6% 4 17,4% 23 100,0% Total 88,1% 11,9% 92,8% 7,2% Positive 54 79,4% 14 20,6% 48 70,6% 20 29,4% Japan n=30 Negative 99 77,3% 29 22,7% 110 85,9% 18 14,1% Total 78,1% 21,9% 91,3% 8,7% Table X The accounting bias in letters to the shareholders CP - AP (causal positive - accounting positive) US Mean Sd Z-value p-value 3,5000 4,1750 4,3788 0,0000 Japan 1,2333 2,0957 2,8284 0,0047 22 AN - CN (accounting negative – causal negative) US -0,5000 1,0086 1,8974 0,0578 Japan -2,3333 2,7957 3,2717 0,0011