Universidade de Lisboa Faculdade de Letras Experimenting with

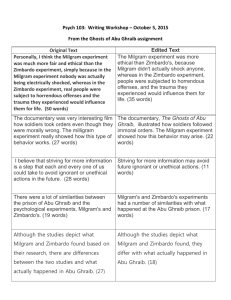

advertisement