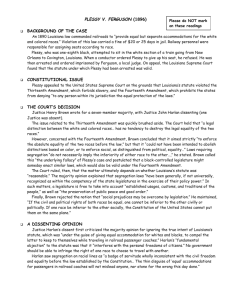

Plessy v. Ferguson

advertisement

Plessy v. Ferguson 163 U.S. 537 (1896) Plessy was a citizen of the United States and a resident of the state of Louisiana, of mixed descent (“…[S]even‐eighths Caucasian and one‐eighth African blood”). On June 7, 1892, he paid for a first‐class passage on the East Louisiana Railway, from New Orleans to Covington, Louisiana and took a vacant seat in a coach “…where passengers of the white race were accommodated.” He was required by the conductor to vacate the coach, and to take a seat in a coach assigned by the railroad for persons not of the white race. When he refused to comply with this directive, he was, with the aid of a police officer, forcibly ejected from the train and taken to a New Orleans Parish jail. At trial for the violation of a State Act providing for separate intrastate railroad cars for “…the white and colored races,” he alleged that the Act was unconstitutional, violating both the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments. On hearing before the state supreme court, the statute was upheld and a writ was sought in the United States Supreme Court. Mr. Justice BROWN delivered the opinion of the court. Mr. Justice Brown, writing for a majority of the Court, defined slavery as involuntary servitude – a state of bondage – and held that the Slaughter‐House Cases made it clear that the Thirteenth Amendment was intended primarily to abolish slavery. (Recognizing the suggestion in that case that the Fourteenth Amendment was a response to a popular political perception that the prior Amendment was inadequate to protect blacks from laws which had been enacted in the Southern states, curtailing their rights in the pursuit of life, liberty, and property). The Civil Rights Cases, he then observed, held that discrimination on the basis of race by “private” operators of places of public accommodations, or amusement could not be regarded as imposing a badge of slavery or servitude upon the person denied accommodation, thus implicating the Thirteenth Amendment. This said, Justice Brown stated – in language which spoke of the social color line in America beyond cavil – that “[A statute] which implies merely a legal distinction between the white and colored races – a distinction which is founded in the color of the two races, and which must always exist so long as white men are distinguished from the other race by color – has no tendency to destroy the legal equality of the two races, or reestablish a state of involuntary servitude.” Again citing the Slaughter‐House Cases, the majority restates that the object of the Fourteenth Amendment was to secure the equality of the two races before the law, but, rejects the assertion that the Amendment could have been intended to “enforce…social equality, or a commingling of the two races upon terms unsatisfactory to either.” By this statement, the majority gives legitimacy to state laws requiring the separation of blacks from whites – e.g., in public schools – holding that this requirement of racial separation “…does not imply the inferiority of either race to the other.” The court concludes with an even more unambiguous recognition of an inevitable social/racial caste, observing that, “[if] the civil and political rights of both races be equal, one cannot be inferior to the other civilly or politically. If one race be inferior to the other socially, the constitution of the United States cannot put them upon the same plane.” [The court also rejected plaintiff’s claim that depriving him of his claim to be white was a deprivation of property without due process, holding that he has the right to pursue an action for damages in the state courts]. Mr. Justice HARLAN dissented, observing at the outset that the Act in question enforces discrimination based solely on race in the use of a public highway [a railroad] by citizens of the United States. On this premise, he rests his argument that the Act in question violates the federal constitution. Justice Harlan observed that the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments, taken together, secure the broad spectrum of civil rights that characterize national citizenship, and declare that state laws shall be the same for black and white citizens, and that “…all persons, whether colored or white, shall stand equal before the laws of the states.” The purpose of the Louisiana Act was unquestionably to require blacks to keep to themselves when traveling in railroad passenger coaches, thus restricting personal liberty solely on the basis of race. It is here that Justice Harlan identifies the majority’s opinion as giving recognition and legitimacy to the notion of a racial caste. He observes that, while the white race may for some time remain the dominant race politically, and in achievements in education, power and wealth, the Constitution must recognize no dominant ruling class on the basis of race. He also observes that state laws which are grounded on a social policy that black citizens are so inferior and degraded that they cannot be allowed to sit in public coaches occupied by white citizens, perpetuates racial hatred and intolerance. He concludes that “…the arbitrary separation of citizens, on the basis of race, while they are on a public highway, is a badge of servitude wholly inconsistent with the civil freedom and the equality before the law established by the constitution.”

![Plessy v. Ferguson (1896) – [Abridged]](http://s2.studylib.net/store/data/016342461_1-691046af92f7c0359d1fa0c33457d603-300x300.png)