PLESSY V. FERGUSON (1896) BACKGROUND OF THE CASE An

advertisement

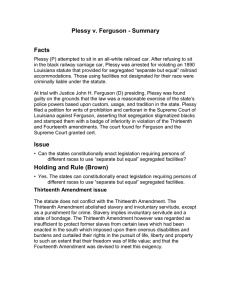

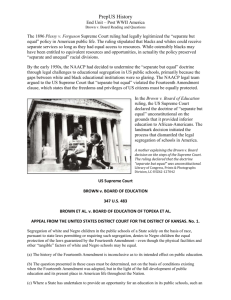

PLESSY V. FERGUSON (1896) BACKGROUND OF THE CASE Please do NOT mark on these readings An 1890 Louisiana law commanded railroads to “provide equal but separate accommodations for the white and colored races.” Violation of this law carried a fine of $20 or 25 days in jail. Railway personnel were responsible for assigning seats according to race. Plessy, who was one-eighth black, attempted to sit in the white section of a train going from New Orleans to Covington, Louisiana. When a conductor ordered Plessy to give up his seat, he refused. He was then arrested and ordered imprisoned by Ferguson, a local judge. On appeal, the Louisiana Supreme Court found that the statute under which Plessy had been arrested was valid. CONSTITUTIONAL ISSUE Plessy appealed to the United States Supreme Court on the grounds that Louisiana’s statute violated the Thirteenth Amendment, which forbids slavery, and the Fourteenth Amendment, which prohibits the states from denying “to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.” THE COURT’S DECISION Justice Henry Brown wrote for a seven-member majority, with Justice John Harlan dissenting (one Justice was absent). The issue related to the Thirteenth Amendment was quickly brushed aside. The Court held that “a legal distinction between the white and colored races… has no tendency to destroy the legal equality of the two races.” However, concerned with the Fourteenth Amendment, Brown concluded that it aimed strictly “to enforce the absolute equality of the two races before the law,” but that it “could not have been intended to abolish distinctions based on color, or to enforce social, as distinguished from political, equality…” Laws requiring segregation “do not necessarily imply the inferiority of either race to the other…,” he stated. Brown called this “the underlying fallacy” of Plessy’s case and postulated that a black-controlled legislature might someday enact similar laws, which would also be valid under the Fourteenth Amendment. The Court ruled, then, that the matter ultimately depends on whether Louisiana’s statute was “reasonable.” The majority opinion explained that segregation laws “have been generally, if not universally, recognized as within the competency of the state legislatures in the exercise of their policy power.” In such matters, a legislature is free to take into account “established usages, customs, and traditions of the people,” as well as “the preservation of public peace and good order.” Finally, Brown rejected the notion that “social prejudices may be overcome by legislation.” He maintained, “If the civil and political rights of both races be equal, one cannot be inferior to the other civilly or politically. If one race be inferior to the other socially, the Constitution of the United States cannot put them on the same plane.” A DISSENTING OPINION Justice Harlan’s dissent first criticized the majority opinion for ignoring the true intent of Louisiana’s statute, which was “under the guise of giving equal accommodation for whites and blacks, to compel the latter to keep to themselves while traveling in railroad passenger coaches.” Harlan’s “fundamental objection” to the statute was that it “interferes with the personal freedoms of citizens.” No government should be able to infringe the right of one race to choose to travel with another. Harlan saw segregation on racial lines as “a badge of servitude wholly inconsistent with the civil freedom and equality before the law established by the Constitution… The thin disguise of ‘equal’ accommodations for passengers in railroad coaches will not mislead anyone, nor atone for the wrong this day done.” BROWN V. BOARD OF EDUCATION OF TOPEKA, KANSAS (1954) BACKGROUND OF THE CASE Brown represents a collection of cases, all decided together. The cases had one common feature: Black children had been denied admission to segregated white public schools. These cases reached the U.S. Supreme Court by way of appeals through lower courts, all of which had ruled in accordance with the decision in Plessy v. Ferguson (1896). The Plessy case determined that separate but equal facilities did not violate the Fourteenth Amendment’s guarantee of “equal protection of the laws.” An earlier case, Sweatt v. Painter (1950) had held that blacks must be admitted to the previously segregated University of Texas Law School because no separate but equal facility existed in the state. In Brown, however, there were findings “that the Negro and white schools involved have been equalized or were being equalized…” CONSTITUTIONAL ISSUE The Brown case was an explicit reappraisal of the question in Plessy v. Ferguson. Did separate but equal facilities violate the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment? THE COURT’S DECISION The Chief Justice Earl Warren wrote the Court’s unanimous decision. Justice Warren began by noting that attempts to determine the precise intent of the Fourteenth Amendment’s original sponsors have proved inconclusive. Even more difficult was any effort to discover its relation to the issue of public schools, as so few were in existence when the Amendment took effect. Warren explained that the Court’s method of examination, then, was to “look to the effect of segregation itself on public education” in order to determine “if segregation in public schools deprives these plaintiffs of the equal protection of the laws.” Warren quoted a Kansas state court ruling, which held that “segregation with the sanction of law, therefore, has a tendency to retard the educational and mental development of Negro children and to deprive them of some of the benefits they would receive in a racially integrated school system.” Likewise, the U.S. Supreme Court concluded that segregation of black school children “generates a feeling of inferiority as to their status in the community that may affect their hearts and minds in a way unlikely ever to be undone… Any language in Plessy v. Ferguson contrary to this finding is rejected.” On this basis the Court concluded, “that in the field of public education the doctrine of ‘separate but equal’ has no place. Separate educational facilities are inherently unequal. Therefore we hold that the plaintiffs… are, by reason of the segregation complained of, deprived of the equal protection of the laws guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment.” Questions: For each court case, complete the following: 1. List the name of the court case 2. Discuss the origins (background) of the case 3. What was the constitutional issue? 4. Explain the significance of the court’s decision 5. After reading both cases, compare (similarities) & contrast (differences) of the two cases.