Olaf Trygvasson and the Conversion of Norway

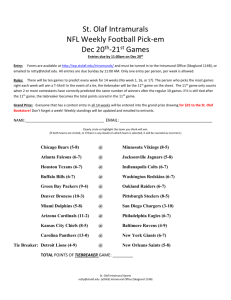

advertisement

“Seat Companion to the Whole People”: Olaf Trygvasson and the Conversion of Norway. “Cattle die and kinsmen die, thyself too soon must die, but one thing never, I ween, will die, -fair fame of one who has earned.” -Havamal, vs. 76 By Michael Warsop Although most of the credit of Christianizing Norway is given to St. Olaf, also known as Olaf II, the first wave of official Christainization started several years before hand with the ascension of Olaf Trggvasson, remembered also as Olaf I, in 995 CE. Although his reign ended five years later in 1000 CE, Olaf managed to unify most of Norway proper under his heavily Christian rule. History tells us the what of the events that occurred around the life of Olaf Trygvasson, but not the whys. As such, this paper will investigate just that question, as to why Olaf converted and was so vehement in his pursuit of a unified, Christian Norway, and will hold that it stemmed from faintly discernible personal reasons and rather apparent political ones. I. First though, a note on sources. There are five primary source documents still extant and available for the use of the modern scholar for research into the life of Olaf Trygvasson, barring several more esoteric sources that mention him in passing. 1 The most well known of these is the Heimskringla, written by Snorri Sturluson around the year 1225. Sturluson, an Icelandic Noble and poet, left a wealth of the old sagas and works of the Norse civilization, and gives the oldest and only lengthy Old Norse account of Olaf Trygvasson.2 A fuller and earlier source is The Saga of Olaf Trygvasson3, written sometime before 1200 and translated into Icelandic sometime after that. It is an obvious influence on Sturluson's sections of the Heimskringla, but it is written in Latin, which may or may not have an effect upon it's usefulness on the subject.4 It's writer, Oddr Snorrason, was a monk at Þingeryrar who claimed to have 1 Amongst these are two sagas, now lost, that Snorrasson refers to in his text, the works of the Icelandic Historians Sæmunder the Wise and Ari the Wise. 2Wilson, David 3 4 M. The Vikings and Their Origins: Scandinavia in the First Millenium. London: Thames and Hudson, 1989. Being a fuller source, this is where most of this papers primary source documentation will come from. For more on the similarities between these two documents, see Andersson's introduction to Snorrason, Oddr. The Saga of Olaf Trygvasson; Translated with Introduction and Notes by Theodore M. Andersson. Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press. 2003. seen a vision of Olaf which inspired him to write the text.5 Supplementary to these two sources are two of the king's sagas, the Historia de Antiquitate Regum and the Historia Norwegiæ. These Latin works are two of the three pieced together works called the Norwegian Synoptics, which are the oldest records of Norwegian history currently in existence. Best dating currently puts them at having been written in the fifteenth century, thus making both Snorrason and Sturluson possible sources for them. However, there is enough variation between the two sets of later documents and their forerunners that it seems apparent that they are from different sources. Both contain stories of the exploits of Olaf Trygvasson. 6 The other source for the history of Olaf Trygvasson is the Anglo-Saxon chronicles, which although short in their entires regarding his activities, as he was a viking conquerer of the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms of the time, spend more time on his activities than many others during the period, and corroborate several elements of the other histories, as well as conflicting with a few others.7 II. Before getting to the question of the nature of Olaf’s conversion, given the esoteric nature of the subject matter, a short version of the life of Olaf Trygvasson is worth discussing. 8 Olaf's father was Tryggvi, a descendant of the Haroldr Finehair who had once united most of Norway and whose children splintered the kingdom as 5Snorrason, p. 1, 136 6Ibid, p. 4 7-The Anglo-Saxon Chronicles, translated by Anne Savage. New York: St. Martin's Press, 1983. p. 3 8 This narrative section is compiled from several primary and secondary sources, and hence some details maybe suffer from slightly different interpretations. The author's direct sources are: Helle, Knut, ed. The Cambridge History of Scandinavia: Volume 1, Prehistory to 1520. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003, Jones, Gwyn. A History of the Vikings. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 1984, Larsen, Karen. A History of Norway. New York: Princeton University Press. 1950, Forte, Angelo, Richard Oram and Frederik Pedersen. Viking Empires. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005. each wanted an inheritance. As such, Tryggvi was considered king of the region known as Vik. His mother was Astriðr, a daughter of a noble named Eirikr. Shortly before Olaf's birth, Tryggvi became involved in a dispute involving the rulership of certain parts of Norway with the other descendants of Haroldr Finehair, notably the sons of one Gunnhildr. She devised a plan to kill Tryggvi so that her own sons would acquire the lands of Tryggvi, and the plan succeeded. Astriðr was forced to flee in late pregnancy, and Olaf was born sometime shortly thereafter. Their destination was the Norse kingdom in Russia where here brother, Sigurðr, was a noble in the court of Valdimarr. Gunnhildr, knowing that if the boy survived her sons position would be in jeopardy, had men sent after Astriðr. This turned out to be unnecessary, as during the journey across the Baltic the ship that Astriðr and Olaf were on was attacked by Slavic vikings, and mother and son were separated by being sold into slavery. Astriðr is lost to history from this point forward, but we know Olaf had three masters during his period as a slave among the Estonians. He was first in the possession of a man named Klerkon, along with the man who had become his foster father with during his flight, named Thorolf, and Thorolf's son Thorgils. Klerkon found Thorolf to be too old, and had him killed immediately. The two boys were then sold to a man named Klerk for a good ram, and later to a man named Heres for a fine cloak. It was from Heres that, nine years later, when Sigurðr was sent to collect taxes from the Estonians for King Valdimarr, Sigurðr found the young Olaf an honoured slave of Heres. Sigurðr noted Olaf's distinctive appearance, and spoke to the boy. Upon hearing who he was, Sigurðr swiftly made purchase of him and his foster brother, and freed them, taking the boys back with him to Russia. It was there that Olaf began his career as a Norse noble. Olaf's career as a Norse noble meant that he learned to command men and fight by leading raids against neighboring kingdoms and into the Baltic. He quickly became a court favorite, which made him the object of jealous nobles and possibly distrusted by Valdimarr himself. As such, Olaf began to sail further afield, eventually ending up in Wendland after a particularly harsh storm. Here he met the Queen Geira, who was a widow and ruled the part of Wendland were Olaf put ashore. After wintering in her court, the two married that spring, as it appeared that Olaf was a powerful lord and Geira was in need of a husband with an army. This marriage put Olaf in a position that, when Emperor Otto III of the Germans went to war with the heathens of Denmark, Olaf was called upon to fight with Otto as Wendland was within the nebulous German realms and at least nominally beholden to Otto. Olaf fought with Otto against Harald of Denmark and Haakon Jarl of Norway, who was at the time in tribute to the Danish king in return for the kings support for his conquests in southern Norway. Otto won the conflict, and one of the conditions of victory was that both Harald and Haakon would convert to Christianity. Of the two, Harald remained converted, but Haakon denounced his conversion almost as soon as he left Denmark. After the Danish campaign, Geira died. Although king of her lands now, Olaf chose not to stay in Wendland and took to viking again. In England (or possibly Ireland,) the widower became invovled with competition for the hand of an Irish Queen, wherein he displaced the ambitions of a local champion who he and his men battled with several times, but never killed their opponents but rather bound them and left them. In 991, the Anglo-Saxon Chronicles record his first raids on the island of England, culminating in the 994 when Æthelred the Unready bought off both Olaf and Svein Forkbeard, whom he had been raiding with, with sixteen thousand pounds and provisions for the winter at Southhampton. Sources differ, but by this time Olaf had either become Christian or was converted as part of the agreement with Æthelred. From here Olaf set sail for Norway. Rumors of his exploits had reached the ear of Haakon Jarl in Norway, as well as his identity as a descendant of Harold Finehair. Haakon extorted Olaf’s two uncles (who, as with many characters in the narrative, just appear out of nowhere,) into luring him to Norway where his men were to ambush him. However, the uncles doublecrossed Haakon and turned the ambush upon the Jarl’s men. After this, due to the excesses of Haakon in his older age, most notably with the women of his domain, as well as the popularity and fame of Olaf, the farmers of Haakon’s land, known today as Trondheim, moved in support of Olaf and added to the ranks of his already impressive force. Haakon was forced to flee, finally coming to rest with only his slave in a hiding place in a pig sty. Olaf and his men were close behind them, and searched the farm where the Jarl was hidden, but to no avail. However, both Haakon and the slave heard when Olaf proclaimed a gold mark for the man who brought him the Jarl’s head. The slave obviously was intrigued by this, and although he did his best to stay awake, eventually the Jarl dozed, at which point the slave swiftly took off his head and went to present it to Olaf. Olaf accepted the head and immediately had the slave killed for doublecrossing his master. For the next five years, Olaf conquered most of Norway and united it under his rule, including the areas that had been under Danish rule. All those he conquered he forced to convert to his faith, and although a few refused, most complied and were duly given places within his kingdom. He made overtures to Sigrid, Queen of Sweden, which would have greatly expanded his kingdom, but due to her insistence on remaining Heathen, he made an enemy of her. 9 Instead he ended up wedding Þyre, the sister of Sveinn, King of Denmark, who had left her brother’s court in a quarrel after abandoning the heathen king Burislav her brother had wed her to, thus setting Olaf in an awkward position with the King of Denmark. 9 Exactly what happened to his Irish wife is unknown. Some scholars believe he in fact kept multiple wives, but only one Christian one, that being Þyre. His reign came to an end in the year 1000 when he was tricked into an errand for his wife that took him to his holdings in Wendland. There, an army composed of the five men he had managed to anger the most descended upon him near the mouth of the river Svolf. These men were the sons of Haakon Jarl, Eirikr and Sveinn, as well as King Olaf the Swede who wished vengeance for the dishonor that Olaf Trygvasson had heaped up on his mother, and Sveinn, King of Denmark, whose sister Olaf had married. Jarl Sigvaldi is also particularly noted for his part in the deception and fighting in the battle, but he was beholden to the King of Denmark and generally held to have had no pariticular ill will towards Olaf. Although Olaf and his men had feared an attack, they had waited for one for sometime, which had failed to materialize, and most of Olaf’s men had left by the time the attack came. Leading from his grand longship, the Short Serpent, Olaf fought the coalition of kings rather than flee, but lost the battle. He was last seen on the bow of his longship, but various sources disagree on exactly what happened at the end of the battle, whether he jumped to his death, merely “disappeared,” or in one case, was carried off to Russia and became a monk! No matter what acutally happened to Olaf, his kingdom was quickly divided amongst those who had killed him and the local Jarls who had initially held power, and much of the country quickly recanted of their conversion. III. Although it is possible that Olaf Trygvasson’s religious campaigning was entirely an affair of politics and convenience, it would be unreasonable to assume so. Historically, people have a faith they hold to be true, and although they maybe converted, if that new faith is not what they then believe, they will often relapse or have symptoms of less than authentic belief that leave traces we can still find in the documents from that time. On this subject, all of the sources we have for Olaf Trygvasson, save one10, are suspect, as they were written by men within the ecclesiastical structure that was generated by Olaf and his spiritual descendants. Nevertheless, there are some things we can deduce, even in these sources, for unless we can hold true that within the writing is some vestige of historical veracity we can examine, the records are essentially worthless! Snorrason states that, during his stay in the court of Valdimarr in Russia, Olaf would not enter the temples, for he felt they were bad and ill tempered gods from the fact that Valdimarr always seemed dour when going to make sacrifice, and that Olaf stayed at the door and never entered the temple. Whilst Snorrason uses this statement as a method of showing his Christian fidelity even before he was converted, if it is a true event, it does say something of Olaf and his religious leanings at the time. Not all men are religious, and even some of the heathens were known to attack their own temples on raids or in piques of rage. 11 This source would indicate that Olaf, for whatever reasons, held no particular love for the heathen religion. 12 His experience as a child slave may also have affected Olaf’s views on religion. Slavery was common in the medieval era, but not in the way we know in later history. Rather, slavery was something one sold oneself into when there were no other options to continue living, and a thing that could be bought out of. In Scandanavia, slaving was a widespread occurance, and being a slave, which they called a Thrall, was the lowest possible position to hold in Scandanavian society. Olaf’s position at the bottom of this social rung may have instilled within him an appreciations for the theology of Christinity that involved humility and submission, as well as such virtues as those espoused by the Beattitudes, even if he did not live them, as was not his place as a Norse noble. Christianity has also been used throughout 10 Sturluson’s Heimskringla. Haakon Jarl is said to have done just this after leaving Denmark and renouncing his conversion. See Snorrason, p.60. 12 Ibid, p.49 11 history to both stand for and against the issue of slavery. Although there is no hard historical evidence for Olaf towards slaves in either direction, an interpretation of the faith that came out with a milder view towards the treatment of slaves and/or against slavery may have found fertile soil in Olaf’s heart.13 Olaf was known to be a man of brutal justice. As was seen with the slave who betrayed Haakon Jarl, Olaf was one to act definitively to keep his position secure. There are multiple records of the savage actions he took to convert his fellow Norwegians, such as when he went to the Orkney Islands. Here, to convince the Jarl Sigurðr Hlọðvisson to convert, he seized the jarl’s son and held him on the prow of his ship and drew his sword, asking the jarl to choose between his faith or his son. 14 However, most of these occurances were in pursuit of the Christian faith. There is a recorded incident where, a favorite of the court having been murdered in Iceland, Olaf found himself eventually in possession of the man, whom he set dogs upon against the pleading of one of his head nobles and a bishop. Once the deed had been done though, the bishop reprimanded him and Olaf felt a great guilt and did penance. 15 This could be an instance of public humility forced by a Church interested in keeping a moral distinction between works against the pagans and works against the good Christian folk, but it could also be a moment of actual conscience on the part of Olaf and an indication of a real moral religiosity. This establishes that there was an actual religiosity to Olaf Trygvasson. The nature of this religiosity is a thing that is harder to determine, although we can already see that is was a very aggressive approach to faith, although this could be due to other factors we will discuss below. However, a look at the conversion tales may help us with the discussion of what Olaf's personal religion was like. 13 14 15 Christiansen, Eric. The Norsemen in the Viking Age. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers, 2002. p. 83 Snorrason, p. 74-75 Ibid, p. 107. The simplest conversion account is the version recorded in Anglo-Saxon Chronicles. In this version, as part of the deal made by Æthelred the Unready, Olaf and Sveinn Forkbeard were baptized by the Archbishop Ælfheah, with the King as their sponsor.16 The most straightforward of the conversion tales, this one is also of course suspect due to the possibility of it being an attempt to lionize the less than popular Æthelred by attaching him to a popular Christian figure. However, Ælfheah is remembered elsewhere as the man who baptized Olaf, so it is likely that if Olaf was already Christian at the time of his English exploits, he at least reaffirmed his faith publicly as part of his deal with Æthelred. 17 There are two other, more involved, conversion stories for Olaf. The Heimskringla and the Historia Norwegiae both have strikingly similar tales of Olaf’s conversion, possibly demonstrating the use of Sturlesson’s work as a source by the writers of the Norwegian Synoptics. These accounts place the conversion of Olaf after Otto’s war with Denmark and the death of Queen Geira, but before his foray to Ireland where he married an Irish noble. In this history, Olaf hears of a seer on the Scilly Islands. Curious about this, he sends one of his men in rich raiment to the fortune teller to test the man’s talents. The seer immediately tells the man he is not the king, but that he should bring his king there. Impressed, Olaf went to see the seer. There, he was told: “You will be a famous king, very devoted to the faith of Christ and most beneficial to your people. For by your efforts the Christian people will become unnumbered. If what I prophesy is true, you may take this as a sign: On the day after tomorrow when you leave your ships, you will see a herd on the shore and you will discover that this has been done by guile because you will be ambushed by your enemies. You will lose your men and you will be carried to your ships on your shield barely alive, but after a week you will be healed by divine 16 17 Savage, p. 144-145. Jones, p. 355. intervention, and when you have recovered, you will be washed in the fountain of life.”18 The Heimskringla goes on to describe the men as “mutineers and men who would destroy him,”19when they ambush Olaf, whereas the Historia merely states that the prophecy came true. Both agree that after this Olaf immediately was baptized, as well as most of his men. Snorrason’s account in The Saga of Olaf Trygvasson is slightly different, but still involves the Scilly Islands. By Snorrason’s reckoning, Olaf returned to Russia after the death of Queen Geira, but before his involvement with Emperor Otto. 20 Whilst wintering in Russia, he had a vivid dream where in he climbed a great height and saw above him a bright and splendid place. Then he heard a voice speaking to him, saying: “Hear me, you who promise to be a good man, for you never worshiped gods or paid them any reverence. But rather you disgraced them, and for that reason your works will be multiplied for good and profitable ends. Still you are very deficient in those qualities that would allow you to be in these regions and make you deserving to live here in eternity, because you do not know your creator and you do now know who the true God is.”21 The voice then identified itself as “the Lord your God,” and urged Olaf to go to Greece and be educated. Olaf then, in his dream, descended the heights he had climbed to, and saw all sorts of punishments and torments awaiting those who did not believe, many of whom he recognized. Upon awakening, Olaf was very moved by the dream, and in a very generalized passage, went to Greece and was educated in the ways of Christianity. 18 Snorrason, p. 160 Sturluson, section 32. 20 This is an inversion of the timing of events in other sources. 21 Snorrason, p. 54. 19 The next passage tells, in much greater detail than the first passage, of how: “We are told that Olaf heard reports of a distinguished man on a certain island called Scilly, not far from Ireland. He was gifted with great natural ability and the prophetic spirit of Almighty God….The man who lived onteh island knew of their coming through his gift of intelligence. He bade all the monks who were there dress magnificently and go to the beach with all their holy relics.”22 The abbot, who was the chieftan of the island according to the account, then preceded to preach to Olaf and baptize him there on that island, along with all his followers. The Anglo-Saxon account makes Olaf’s conversion a simple matter of political expediency, but the other histories paint a far different picture. The dream sequence described by Snorrason is a bit suspect, but the baptism on Scilly seems to be corroborated by both sources, as well as the presence of a soothsayer of some variety. Both stories have a thread in the narrative about Olaf’s inherent dislike of the polytheistic heathen faith of his people, which could very possibly be editorialization of the authors. Still, the sources also require a certain nuministic intervention for Olaf to actually be converted, which could indicate that in fact Olaf did consult a soothsayer on Scilly that lead to his baptism. This could mean that Olaf was merely ambivalent about the heathen gods, and that it took an actual religious moment to incite religious fervor within his breast. IV Whilst the reasons behind the personal motivations for Olaf’s conversion maybe difficult to evoke from the records, the political reasonings behind this choice 22 Ibid, p. 55 are manifold and discernible. Olaf was known for being a wide traveler in all the accounts of his life, and being a Norse noble, this would appear to be an easily surmised truth, as by the late period one trained a young noble by sending him raiding with parties of trusted men. 23 In his travels, he must have seen that the rest of the world was quickly or slowly Christianizing (or in the case of places such as Spain, becoming Muslim.) More directly, there were several men whom he had become allied with or whom he could become allied with by becoming Christian. Although Æthelred the Unready had bought him off, that still said a great deal for the wealth and power of the AngloSaxon king that he could command such funds when needed. King Harald of Denmark had stayed a converted man after the war with the Germans, thus making him a potential ally in Olaf’s conquests of Norway, as well as an enemy required by religion to attempt to resolve any disputes between the two of them peaceably should a problem arise, such as when Olaf took some of the lands in Southern Norway that had been recently ruled by the Danes. Olaf had served under Otto III before, and knew the power that the Emporer would wield, as well as being a neighbor to him to the south via his holdings in Wendland. Becoming a Christian would have made Olaf Trygvasson several powerful allies. 24 A trend amongst the men noted above also probably did not escape Olaf’s notice, that they were powerful men who ruled over kingdoms that were more organized and richer for it than Norway. Becoming Christian allowed for this in a number of ways. Normalized trade with the continent could do wonders for the economy, allowing both for the import of foreign goods in a fashion less haphazard than viking, as well as creating a market to stimulate markets at home by giving them 23 Graham-Campbell, James. The Viking World. London: Frances Lincoln Limited, 2001. p. 68. 24 Forte, p. 186. an outlet for a growing material excess due to better conditions in Scandanavia as well as the increased capitol that had accrued in the area due to two centuries of raiding. The church also brought with it an organized infrastructure when it converted a region, which helped maintain stability in the area as well as provide multiple civil services, such as education, both of which the previous heathen ways failed to do on an appreciable scale. Olaf clearly recognized the ability of a Christian nation to organize and function, and given the alternative of a continued fractitious set of nation states such as had been the norm in Norway, conversion must have been a very appealing option. In fact, Olaf, when addressing a great feast he had called at Hlaðir, said: “It is well known to all of you chieftans in Þroendalog that I am a Christian and that I urge a religion different from the one you wish to have. I have diminished the standing of your gods because I would wish to shed their authority so that I might as a consequence maintain my rule.”25 Olaf clearly saw his rule as tied to the conversion of Norway to Christianity. This is also evident in his handling of his converts. Repeatedly, he offers the Jarl’s he deals with the option of death (or the death of a loved one, confiscation of property, or something equally damaging,) or conversion and a place in his kingdom. The last clause is the important part. To all those we have records of Olaf seeking to convert, conversion is synonymous with a position of power and respect on the same level as their previous position. Olaf clearly equated Christianity with power in his government, and by doing so most likely spread the same attitude to those within his domain, helping to explain both the wide spread success of his conversions, and the speed at which many of his former vassals rescinded on their faith as soon as his rule 25 Snorrason, p. 81. was gone.26 One further insight available to us comes from the story of the Conversion of Iceland. During his five year reign, Olaf expended a great deal of time and energy attempting to convert Iceland by missionaries, as Iceland was far beyond his political reach. Prior to the Allðing27 in the year 1000 CE, his last missionary, one Hjalti, had in fact been sentence to lesser outlawry in Iceland for killing several men. The continued failures of his missionaries is said to have infuriated him, to the point that he had at one point confiscated the ships of several Icelanders in port and would have killed them had not cooler heads prevailed. 28 In the summer of 1000 CE, having wintered with King Olaf, Hjalti and his fellow Icelander Gizurr the White set sail for Iceland with a priest named Þormoðr. After reaching the island, initially Hjalti was left behind because of his sentence that was still in place, but when the two men, who had at this point collected most of the Christians in Iceland (for Olaf's men had made some headway on the island,) came near the plain of Þingvellir where the Law Rock was, they found that many of the heathens barred their way with force, and quickly Hjalti was called to their aid in case fighting did break out.29 However, no violence occurred that day, and on the following day Hjalti and Gizurr spoke their piece at the Allðing. Once this had been done, the men on the plain divided themselves between those who were Christian and those who were heathen, and declared themselves out of law with each other. The heathens immediately left, but the Christians stayed and bribed the Law Speaker, Þorgeirr, to speak what laws the Christians should be beholden to, as they no longer held to the 26 27 Christiansen, p. 83. This was a meeting of all the free men of Iceland to decide upon th e laws of Iceland for the year. It was presided over by the Law Speaker, whose place it was to listen to all the men and then decide what was the best thing to do. 28Snorrason, 29Ibid, p. 88-89. p90-91. same laws as the heathens. This he did, then retreated to his tent and laid down with his cloak spread over his head in silence for the rest of that day and the following night.30 Given that the missionaries of Olaf apparently talked at length with the Law Speaker, and that they had in fact been charge to do so by Olaf, the pronouncement of the next morning made by Þorgeirr, both by this inference as well as it's insight as an observation of the times, may speak volumes as to the motivating ideas behind Olaf's drive to convert Norway. The next day, before the gathered audience, the Law Speaker declared that it would not do for the people of the country to have more than one law. He spoke of how Denmark and Norway had fought and struggled until peace had been the only option, even though they did not want it. “It seems to me advisable that we not yield to those who are most eager to kindle hostility. We should rather mediate the matter so that each party gets some part of what it desires, but we should have one law and religion.”31 Both sides saw this as a wise statement, and both also thought that their views would win out, as the heathens thought surely that the heathen Law Speaker would not pronounce against them, and the Christians had a deal with him. Þorgeirr pronounced in favor of the Christians, officially converting Iceland, not out of faith, but out of necessity for the peace of the land. This would seem to be the type of sentiment, given what we have seen, that would have been in agreement with Olaf. He wanted a united kingdom under him, and most likely saw that one, unified religion would do this. That he was Christian 30 The exact importance of laying beneath the cloak is not entirely clear, but may have been a religious action whose meaning has been lost. 31Ibid, p. 91. and that Christianity espouses this sort of ideology would go hand in hand with that belief. The important accounts of who Olaf was are lost to history, as they were most likely only oral stories remembered by those who knew him. However, by studying the sources we do have, we constructed a picture of a man who was religious in a personal sense, and seems to have had a genuine religious experience that motivated his rule, as well as a possible early ambivalence for the religions of his people. We also see a man who had seen the wider world outside of Scandanavia, and understood the values of a unified state with a unified religion, preferably one connected to his neighbors. Perhaps reform and standardization of the heathen faiths would have been possible, but it was both easier and more profitable to convert to an already extant faith, even without accounting for a personal religious belief. As stated at the beginning of the paper, the credit for Christianizing Norway is often given to Olaf's later namesake, Olaf II, the patron saint of Norway. However, without the work Olaf Trygvasson undertook, this would have been a much harder task, and it seems that Olaf's work was one he found both to be a joy, and of profit. Bibliography -Snorrason, Oddr. The Saga of Olaf Trygvasson; Translated with Introduction and Notes by Theodore M. Andersson. Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, 2003. -The Anglo-Saxon Chronicles, translated by Anne Savage. New York: St. Martin's Press, 1983. -Sturluson, Snorri. Heimskringla. http://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Heimskringla. Accessed November 19, 2006. -Kendrick, T.D. A History of the Vikings. New York: Barnes & Noble Inc. 1968. -Page, R.I. Chronicles of the Vikings: Records, Memorials, and Myths. Toronto and Buffalo: University of Toronto Press, 1998. -Sawyer, Birgit and Peter. Medieval Scandanavia: From Conversion to Reformation, circa 8001500. Minneapolis and London: University of Minnesota Press, 1993. -Forte, Angelo, Richard Oram and Frederik Pedersen. Viking Empires. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005. -Larsen, Karen. A History of Norway. New York: Princeton University Press. 1950. -Christiansen, Eric. The Norsemen in the Viking Age. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers, 2002. -Derry, T. K. A History of Scandinavia: Norway, Sweden, Iceland, Denmark, Finland, and Iceland. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1979. -Jones, Gwyn. A History of the Vikings. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 1984. -Turville-Petre, G. The Heroic Age of Scandinavia. London: William Brendon and Son, Ltd., 1951. -Helle, Knut, ed. The Cambridge History of Scandinavia: Volume 1, Prehistory to 1520. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003. -Wilson, David M. The Vikings and Their Origins: Scandinavia in the First Millenium. London: Thames and Hudson, 1989. -Henrikson, Edvard, ed. Scandinavia Past and Present: From Viking Age to Absolute Monarchy. Denmark: Arnkrone, 1959. -Graham-Campbell, James. The Viking World. London: Frances Lincoln Limited, 2001.