THE PRAGMATIC PLEA: EXPANDING USE OF THE ALFORD PLEA

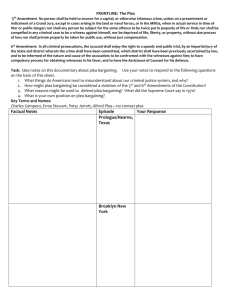

advertisement