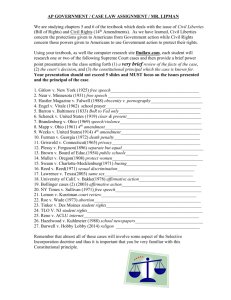

Snyder v. Phelps

advertisement

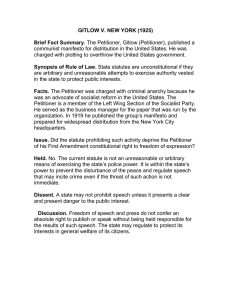

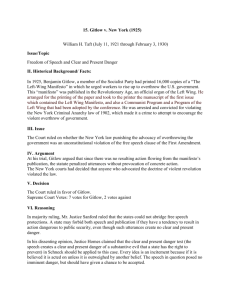

Stuart Wallace Into to Legal Studies Case Brief #2 Spring 2015 Case Brief: Gitlow v. New York Case Information: Gitlow v. New York (1925) - decided by the U.S. Supreme Court Relevant Circumstances & Facts: Benjamin Gitlow, the petitioner, acted as manager of a newspaper publisher for The Left Wing Section of the Socialist Party. In 1919 Gitlow, in accordance with the organization itself, published "Left-Wing Manifesto" urging class strikes and "other measures" as a means of instituting socialism in the United States. Gitlow was indicted on criminal anarchy charges under a New York statute set forth in 1902 that outlawed the advocating of upheaval of an organized government entity. Gitlow petitioned the validity and constitutionality of the New York statute under the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution. Constitutional Provision: Gitlow alleged that his conviction, under New York state law, violated the Fourteenth Amendment and its Due Process Clause. New York held that the freedom of speech guaranteed by the First Amendment was not violated by the conviction and indictment of Gitlow. New York made it clear that its interests in suppressing the anarchyinciting publication of the Left Wing Section of the Socialist Party justified the arrest and conviction. The Supreme Court was consequently asked to resolve the following question: Did the statute prohibiting the petitioner (Gitlow) from distributing the publication deny the individual of his First Amendment right to freedom of expression? In addition, is the main purpose of the statute to protect the public interest, or to suppress the general public in such a way as to unreasonably exercise the state's police power? Legal Outcome: In a 7-2 ruling, the Court held for New York, affirming the New York state court ruling that the arrest and conviction of Gitlow did not violate his First Amendment rights, as the Constitution protects the expression of "abstract doctrine and academic discussion." The Constitution does not protect against calls to action in an attempt to overthrow government in any way deemed unlawful. The Constitution's protection extends to those looking to engage in scholarly discussion or reform of government by lawful and constitutional means. Legal Reasoning of the Majority: In delivering the opinion of the Court, Justice Sanford held that: • Gitlow's actions (publication and attempt to mass distribute) constituted expressive conduct, allowing for a First Amendment claim. • The statute in question "does not penalize the utterance or publication of abstract 'doctrine' or academic discussion having no quality of incitement to any concrete action" as stated in Gitlow v. New York (1925). • Although protection is provided to publications advocating for reform, it does not extend to the use of "calls to action" and speech looking to incite action to overthrow a governmental body by force or any unlawful means, both of which are advocated by The Manifesto. • New York's stated interest is in protecting the welfare of the general public, not in suppressing the voice or exercising the state's police power on its people. Legal Doctrine: The majority of the justices: 1. Pointed out that the freedom of speech and of the press does not allow for the absolute right to speak or publish anything an individual may choose, regardless of language, so long as that expression generates harmful situations for the public. 2. Reaffirmed past precedents that state that the state's interest in preventing anarchy and the reckless expression of reform ideas does not constitute an unreasonable exercising of police power, nor does it pose a constitutional dilemma in which the state is overstepping its bounds. 3. Held that the State of New York's vested interest in the suppression of such expressive acts inciting anarchy is at the root of its very own existence. A governing body is nothing without the ability to maintain its power and control. Other Points of View: • Justices Holmes and Brandeis dissented: In Schenk v. United States, 249 U.S. 47 (1919), the following criterion applies: "The question in every case is whether the words used are used in such circumstances and are of such a nature as to create a clear and present danger that they will bring about the substantive evils that [the state] has a right to prevent." The only difference between an idea and an incitement, according to Justice Holmes, is based upon the speaker's enthusiasm and expectation for action. The lack of a specific time and place set for an orchestrated uprising indicates a level of innocence with which the law may not necessarily deal.