Subjects, Topics and the Interpretation of Referential pro.

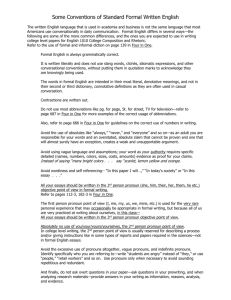

advertisement