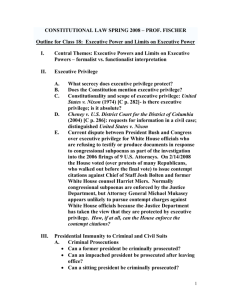

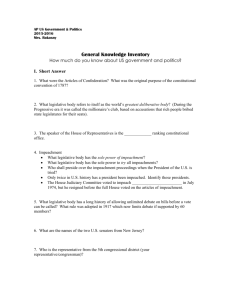

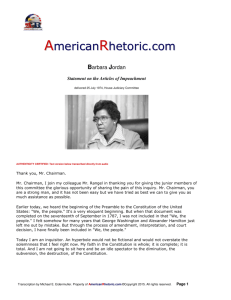

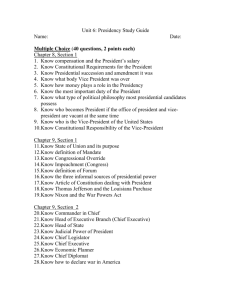

impeachment and presidential immunity

advertisement