United States v. Nixon

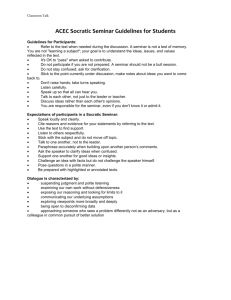

advertisement

Socratic Seminar Confronting United States v. Nixon A Discussion on Judicial Review, Executive Privilege, and the Balance of Powers Designed by Dan Geroe Topic: Executive Privilege, Judicial Review, and Checks and Balances Overview: On June 17, 1972, five men were arrested for breaking and entering into the Democratic National Committee headquarters at the Watergate complex. Reporters Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein for the Washington Post uncovered information suggesting the cover-up led deep into the Justice Department, the FBI, the CIA, and the White House. The FBI eventually was able to connect payments to the burglars to a slush fund used by President Nixon’s (Committee for the Re-Election of the President). It began to appear that many current and former members of Nixon’s staff had been responsible for the many aspects of the break-in. It was discovered that President Nixon had a tape recording system in his office and that he had recorded many conversations. It was believed that these tapes would implicate the President in the cover-up. Nixon refused to hand over the tapes until the Supreme Court ruled he had to, leading his resignation, and eventual pardon by successor President Gerald Ford. The Watergate Cover-Up is the quintessential American political scandal for the 20th century. Nothing, not the Monica Lewinsky Affair, not the Dan Qualye “Potatoe” incident, has come close to it. In fact, it is a common practice in American political journalism to take whatever is the focus of any current political scandal and attach “gate” to the end of it. It rocked the country’s faith in its political system. And yet, the case that determined Nixon’s fate, United States v Nixon, is one of the most ensuring and inspiring cases in American history. It reminded the country once again that no man is better than any other in the eyes of American law. The criminal justice system applies equally to everybody. The President cannot keep information away from the courts, or the American public, unless it is in the strict security interests of the United States. This case made it clear that no President can abuse power the way Nixon allegedly did and expect to get away with it. It gave Americans reason to believe in their government, and their constitution again. In this lesson, students will discuss the many themes, issues, and opinions that make up the United States v Nixon case, including Judicial Review, Executive Privilege, and the Checks and Balances of American Power. Students will read a legal brief on the case to get a basic understanding of what happened that lead up to the Supreme Court ruling. They will briefly examine the arguments (summarized) used by the President’s attorneys and by the Special Prosecutor, as well as well as a summarized version of the court’s ruling. They will also use Excerpts from the Court’s ruling itself to dig deeper into the details of why and when a President can use his executive privilege. They will answer an Entrance Ticket prior to coming into class the day of the lesson, answering questions to make sure they understand what happened in the case. Using the form of a Socratic Seminar, students will finally address the issues they determined to be important. The teacher, serving as a guide and moderator, will pose questions to help students address the material that he/she feels is important. Upon finishing the seminar, students will complete an “Exit Ticket” so they might share and express what they got out of the lesson. Hopefully, students will leave this lesson not only with a better understanding of executive privilege and judicial review, but with a better understanding of what they themselves believe about government power, how it should be used, and how it should be divided. Grade/Class: This lesson was designed for a ninety-minute Senior-level US Government Class. Further, this lesson has been designed to take place in the mid-to-late curriculum, after students have had a fair amount of experience confronting different types of textual sources. This course was also designed with a classroom size of 28 students in mind. Should the class be any bigger than this, it might be necessary to divide the class in half and actually have two seminars. Again, this is not mandatory; if the teacher feels that there is enough time for a large number of students to participate in the one seminar, that is up to his/her discretion. Length: This lesson is designed to take approximately 70 minutes on the day of the lesson, and to require 5-10 minutes of preparation and background discussion prior to the actual day of the seminar. This lesson really should not be broken up into two sections to accommodate a fifty minute class. However, if a teacher wishes to try this, it is better that the lesson is split between the Opening and Core Questions, rather than between the Core Questions and the Debriefing. If a teacher breaks the lesson up into two classes, then it is important that the class review what was said and discussed in the prior class before moving on to new material. Background Information: Students attempting this lesson should have already addressed the idea of “checks and balances” at a basic level. They also should have a basic understanding of the powers that each branch of government has; specifically, they should understand the concept of “Judicial Review.” Though they don’t need to be experts on the subject, they should at least know what it means (that the legislative and executive actions are subject to review by the judiciary). Students at this level should have also taken US History; events like Watergate, and the resignation of Richard Nixon, should not be foreign to them. However, more recent historical events, like Watergate, are often very briefly examined. Therefore, as the lesson suggests, teachers might want to briefly examine what exactly happened during the Watergate scandal prior to passing out the Legal Briefs and Excerpts contained in the lesson. Using the introduction in the Overview as a guide might help determine what is important. Instructional Model: A Socratic Seminar is (as defined by Larson and Keiper) a teacher-directed questioning session that encourages students to think deeply about issues. Personally, I’m not sure I would use the word “directed” in the definition; to direct suggests leading, and that is not how a Socratic Seminar works. I might prefer to use the word “guide”; within a Socratic Seminar, the teacher uses questions (both planned and improvised) to guide the students as they lead themselves to deeper learning. They do the digging; the teacher just gives them instructions and tips on how to use the shovel. A Socratic Seminar begins with a source; a text, a dictation, a movie/documentary, or even a song. This source is read and analyzed by the class individually. Students then lead a discussion together, as a group, with the teacher serving as a guide and moderator. The teacher serves to make sure the students stay on task, and to ask questions that will help them dig deeper than they would if they were entirely without supervision. However, it is still primarily up to the students to take the seminar where they want it to go. They will mostly address the issues, themes, concepts, and ideas that they related to, and that they found important. The Socratic Seminar allows students to dig deep into sources a find greater meaning in the themes presented. Most importantly, students are allowed to identify and build upon these themes themselves; teachers only serve as guides. Rationale: The case of United States v Nixon is one of the most important cases in recent United States History, dealing with perhaps that largest scandal in the history of American politics. It is easy to miss the important government issues in the case, and become enamored with the glamour behind the scandal that destroyed an Administration. However, there are some very deep and meaningful themes about government discussed in this case. Particularly, how power in managed and shared within the three branches of the United States government. President Nixon believed that, as the President of the United States, his private conversations were protected by “executive privilege”; meaning, he did not have to share his recorded conversations, or any other private material, with the judicial branch. In essence, Nixon was making himself immune to many aspects of the criminal justice system. The Supreme Court ended up ruling against Nixon. This case brings up many fascinating questions: Is the President different from normal Americans? Should he be treated differently? When is it okay to keep private material out of the hands of the public or courts? Does Judicial Review grant the Judicial Branch ultimate supremacy over the other branches of government? These are questions with no clear “black- and-white” answer. Rather, these a questions that require reflection and investigation, both with regards to the evidence of the case and with one’s own philosophical beliefs. This case works well in a Socratic Seminar format because students will get a chance to address which questions speak to them the most. They will get a chance to share their multiple, differing views with each other using the same source material. With a teacher capable of guiding them towards the right questions, they won’t only get a strong understanding of how our government works, but they will also (hopefully) achieve a bit of self-enlightenment; what they believe about power, how they view the different branches of government, and what they would do in controversial situations regarding the fragile balance of governing power in our country. Objectives: Academic: 1) Students will review material addressing the historical background and reasoning of the Supreme Court case of United States v Nixon prior to taking part in the Socratic Seminar. 2) Students will be able to recognize, and effectively comment on the limits of, executive privilege by the end of the conversation in class. (GOVT 7)(NCSS 6) 3) Students will show and express knowledge and understanding the power of judicial review during the conversation, and the relate the importance it has in our systems of checks and balances. (GOVT 7)(GOVT 10)(NCSS 6) 4) Students will complete an “Exit Ticket”, focusing on reflection and application of the material learn, at the end of the seminar that allow them to express what they have learned and how their thoughts have developed. (NCSS 4) Intellectual: 5) Students will progressively build off of the arguments, opinions, and assertions of their fellow students in the seminar. 6) Students will be able to comment on hypothetical real-world situations based on conclusions made in Nixon about judicial review, executive privilege, and checks and balances. (NCSS 10) Skill-based: 7) Students will share an opinion, ask a question, or actively participate in some other way at least once during the seminar. 8) Students will share their opinions in a clear, concise, and coherent manner. 9) Students will construct well worded responses to their “Exit Ticket” using proper English. Assessment: I. Participation –Most of the assessment in this seminar will come from student participation. The participation itself primarily takes the form of Formative Assessment within the seminar. a. Each individual student must complete the “Entrance Ticket” to participate – The Entrance ticket is designed to show that the student understands the details of the case II. well enough to participate in a group discussion on the subject. The ticket itself should not be collected, as it can help students address the case throughout the discussion. b. Every student should participate at least once – Students should participate at least once during the debate. This is important for Formative Assessment; a teacher can’t determine what the student is learning, or whether the student is trying to absorb the information, unless the student shows that he/she is actively aware of the conversation. c. Responses should build upon each other- Students can show they are progressing and growing by allowing their responses to build upon one another. Reflection upon previous responses, rather than just the response immediately prior, can also be used to show growth. d. Contributions are thoughtful and relevant – When students participate in the conversation, teachers need to be make sure that the participation shows actual effort and thought. A random contribution simply to meet the “at least once” requirement is equal to no contribution at all. i. Help them make it relevant – If a student’s contribution appears to be shallow, help them develop the thought by asking them what they mean, or asking them to elaborate/think deeper. Asking why they came to the conclusions they did is a great way to make them think on deeper levels. For example: “Why do you think that?” “Why is that important to note?” “Why should the President/the courts think that way?” ii. Encourage other students to assist – Ask another student if they have anything they’d like to add, counter, or build off of a student’s comments if you feel that the students isn’t digging as deep as he/she could. Once one student has offered a response, give the students a chance to respond in turn and clarify his or her position/observation. This will help them develop thoughtful and relevant contributions, and make sure that everybody has a fair chance to participate. iii. Explain why this is important – Should students ask why they need to go into further detail with their responses, explain to them that you are trying to get them to make deeper connections with the material, and it’s important in the structure and reasoning behind the United States government. Exit Ticket – Students will be assigned an “Exit Ticket” after completing the seminar on United States v Nixon. This “Exit Ticket” will serve as Summative Assessment, and will help teachers determine what students come away with from this lesson. a. Students will put serious thought and effort into each response – A large number of the responses on the Exit Ticket are open-ended, or opinion based. Because there is not necessarily “one right answer”, students need to show that they have put some time and thought into their responses. b. Students used thoughts, opinions, or assertions from the seminar in their responses – Students need to use things they have gathered from the seminar in constructing their responses. This shows not only that they were paying attention during the seminar, but that they have been considering their classmates responses. c. Student’s responses will be clear and well-written – Response to the written “Exit Ticket” will be well constructed, readable responses. This means complete sentences and thoughts. Students who answer in bullet points, incomplete sentences, or show little-to-no structure in their response will not receive full credit. Content and Instruction Strategies I. Seminar Preparation – Students should be given both the “Legal Brief of United States v Nixon” and the “Excerpts from the Supreme Court’s ruling in United States v Nixon” a few days prior to the actual seminar. Though the Brief is supposed to be read first, and give a relatively brief review of the case, the excerpts give more detailed reasoning about why the case was reasoned the way it was. a. Seminar Text Importance – It is important that you explain to students why this text is important; what are some of the values, ideas, and concepts found within this text. Students need to know that this text (the Reasoning and Brief) explain how the United States Government’s design works to prevent abuses of power; how one branch of government is kept from overwhelming the other branches. Students should know that, going into this text, that should be looking at the concepts and themes of Executive Privilege, Judicial Review, Abuse of Power, etc. Students should also think about what Nixon did that forced him into court; the alleged involvement with the DNC break-in, the alleged cover-up, and the eventual resignation from the Presidency. What would cause a President to go to these extremes? b. Entrance Ticket – Alongside the Brief and the Rulings, students should be given an “Entrance Ticket.” Students need to be informed that to be able to participate in the seminar, and thus in order to receive full credit, they must complete the entrance ticket. Students who do not complete the entrance ticket will watch the seminar, take notes, and maybe even be asked to write notes on the board/document camera. However, they will not be allowed to share in the seminar. c. Advice – Students need to know that it will probably take them more than one sitting to read through the Rulings. The language is tough, the concepts large, and the material difficult. They will most likely need to read with a dictionary next to them. Let them know they need to give themselves plenty of time when addressing this material, particularly if their experience with difficult texts is limited. d. Discussion Preparation – Students will be given instructions on what is expected from them during the actual seminar. It is important that you give them these expectations prior to them reading the texts. They should know what they need before they do their research. i. Students need to contribute to the discussion at least once – Students need to know that they are expected to participate at least once during the seminar. This means a thoughtful, reflective comment; just saying something during the debate so that you might say you contributed does not count. ii. Students need to build off of other students responses – Students need to understand that part of a seminar requires students building of other assertions, thoughts, ideas, or comments. Rather than a series of unconnected observations, a seminar requires students growing off of each other. iii. Students should try to be clear and articulate in their responses – Because students are going to have their classmates building off of their responses, it is important for students to try to be very clear and articulate. iv. Students should use the documents in citing evidence – Though this lesson does not insist that students stick solely to the evidence provided to them, remind them that it is better that they site parts of the text in their responses. This puts all participants in the seminar on the same level; they’ve all read the material being referenced. Again, outside sources are not banned, but let students know that as a the moderator, you won’t let them get too far away from the text. v. Students shouldn’t hesitate in asking questions – If one students says something that confuses another, the confused students should know that is perfectly ok to ask for a bit of clarification or further explanation. e. Answer Questions on Watergate – No is the time to answer any questions students might have about the Watergate Scandal. Discussion of this topic is limited in the brief, as it is assumed that most students got a basic understanding of it in US History. However, it is very possible that some students still do not understand this part of the history. i. Ask a student first – Ask in any of the students in the class feel they know enough about Watergate to share. If they do, let them speak. ii. Fill in the gaps – If no student felt comfortable sharing, or if the students who shared missed some key parts/were inaccurate on a few issues, it is important that you step in and clarify thing. This should not take long; anymore than five minutes spent on this is overkill. II. Room Arrangement – On the day of the seminar, the room needs to be properly arranged for a discussion. Though the ultimate details of the room arrangement will very from teacher to teacher, a circle or a semicircle are the most recommended ways to have students arranged. This will allow them to see their classmates without having to spend a great deal of time twisting and turning in their seats. a. Seats can either be assigned or up to students – If you know some students have difficulties not paying attention when seated together, it might be best if you assign seating during this seminar. Remember, it is essential that students participate and pay attention in this assignment. They can’t do that if they are talking on the side. III. Day-of-Preparation (5 minutes)– To prepare students for the seminar discussion, a teacher will need to do a few key things: a. Students will need to quickly re-arrange seats in the classroom (if necessary) and get into their seats. b. Students need to be reminded of what is expected of them in the seminar. Namely: i. Students should contribute at least once ii. Students should build off other responses iii. Students should remember to cite evidence from the text in responses iv. Students should try to be clear and articulate in responses v. Students should not be afraid to ask other students for clarification if they do not understand. c. Students will need to need to take out their Entrance Tickets to prove they are ready to participate in the seminar.- A teacher or an assistant should quickly check to determine whether all students have finished the Entrance Ticket. Those who have not need to be informed that while they may take notes, or perform other jobs assigned by the teacher. Some of these jobs may include: i. Official Note Taker – Somebody who records everything that is said. ii. Whiteboard Writer/Chalkboard Writer/Overhead Writer – This student keeps track of the major themes, ideas, and facts that are essential to the case. The student writes these on a widely visible medium, such as a whiteboard, or on the overhead. 1. The Importance of the Jobs – These jobs can actually be very important to some students. A teacher should stress this while assigning these rolls. In fact, a teacher might want to take over one of these rolls (particularly number ii) if all students bring their ticket to participate. IV. Opening Questions (25 minutes)– Prior to asking these questions, remind students of what is expected of them in the discussion; what skills are they expected to show? The opening questions are identical to those on the Entrance Ticket. For this reason, it is best if you only check to see if they have completed the Ticket, rather than collecting it. Let students use the ticket as a form of notes they can have throughout the environment. The idea behind this is to start of the seminar with “softball questions.” These questions are: a. What were the background events that lead up to this case? b. What are the issues presented in this case? Why do you think these issues would matter? c. What did the Supreme Court Rule? Why did it rule that way? d. What happened immediately after the trial? What does this imply to you? Do you think it is fair to make this implication? i. Did students read the text? – These questions are just to establish a background for the case; what happened in the case? What did the Supreme Court say and why? What did Nixon do after the ruling? ii. Did students understand the basic principles of the text? – Students can share with other students what they got out of the text. This will make sure that students who struggled with the material can learn from people who found more success. iii. Confidence – In being able to answer questions they directly prepared for first, students will be encouraged to speak out more often. I’ve noticed, during model Socratic Seminars, that things are the slowest at the beginning. I think that by making the questions at the beginning easier, students will be more likely to contribute early, and thus contribute throughout the discussion. e. Teachers are welcome to add new questions to this list – Either prior to the lesson, or after hearing a particular student response, teachers are welcome to come up with new Opening Questions. In fact, it is the teacher’s duty in this lesson to be a good listener. If, during these opening questions, an opportunity for a new question emerges, a moderator or teacher shouldn’t necessarily shy away from it. V. Core Questions (25 Minutes): These questions are focused less on understanding the basic levels of the text, and focused more on higher-order thinking. These questions will require students to address the themes of the text, and analyze them in depth as well as apply them to novel situations. Suggested core questions are listed below: a. Why would it be important in a free, democratic society for a President to not be able to keep all conversations totally private? i. Specifically, what did the Court say about this issue? What connections can you make from the reading? b. What does the Supreme Court’s ruling mean for the larger concept of Checks and Balances? i. Where in the text is your answer supported? c. With the courts forcing Nixon to hand over his tapes, and the President’s eventual resignation, what does this say for the Court’s power of Judicial Review? d. e. f. g. h. VI. i. Relate this to what you already know about the Supreme Court (for example, lifetime appointments, unelected individuals, etc.) Do you agree with the Supreme Court’s ruling? i. If not, how and why would you have done things differently? ii. If you agree, why? Scholars cite this case as a clear example of Checks and Balances in the United States. Do you think that this is a good example? i. Why? Please use the text in your answer. 1. (If students remark on the Supreme Court appearing more powerful than the Presidency) What does that say about Judicial Review? Why do you think Judicial Review is such an important principle in our government system? In what circumstances did the court say a Presidential conversation was immune to the judicial system? i. Do you agree or disagree with this sentiment? Why? Please use the text, or historical examples, in your reasoning. Any questions that the teacher devises based on the conversations are also encouraged. Because students lead the conversation, not the teacher, it is important that the teacher be able to react to the students, and see the opportunities to ask questions. Debriefing (20 minutes): Once the seminar is over, students will have a chance to react to the material they just learned. a. Show the clip of Richard Nixon apologizing: Once the seminar has ended, play this youtube clip of Richard Nixon. Explain to them that this is from the Frost/Nixon interviews. Let them know that while Nixon never explicitly admitted that he ordered the break-in at the DNC, he admitted to having made mistakes and “letting people down.” It is important that you download this clip ahead of time, as many schools won’t let you connect to youtube. The clip can be found here: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tuwfBbZUEPM&feature=related b. Last Thoughts: Have students get together in pairs of two. Each student needs to determine what they think the most important part of the discussion was. This can take the form of a summary, an observation, or even a complaint. Students will then take both of their assertions and combine it into one “thought.” This should take no more than five minutes. Students will then share this thought with the class in a group. i. Students are also encouraged to come up with a criticism they had of a discussion; either personal failures that they would like to work, or about the discussion as a whole and parts that they don’t think worked as well. If they have such a criticism, it should be shared with the class. ii. Students should all have more than one “parting thought” prepared in case somebody else already says the one they came up with. They can mention they noticed the same thing, but only if they took the same observation a different way, or disagrees with the conclusions other students drew. iii. Tell students that if one of the partners has already shared with the class during the discussion, and another hasn’t, let the student who hasn’t spoken yet be the student who explains and elaborates on the “last thoughts.” c. Give Students the “Exit Ticket” to complete: It is important that students do this Exit Ticket immediately after the seminar, rather than assigning it for homework. This will allow things to be fresh in students’ minds. Keep up any “ideas, themes, concepts” that were written on an overhead or on the board. Allow students to use their notes in completing the assignment. i. The Exit Ticket consists of five open-ended questions – The Exit Ticket is designed so that students can reflect and expand upon what was said during the seminar. The questions are: 1. What did you contribute to the discussion? 2. What was the most interesting this you heard one of your classmates say? 3. What was something you didn’t know or understand coming into the seminar that you now have a better understanding of? 4. Explain why you agree or disagree with the Supreme Court’s decision. 5. Imagine this hypothetical situation: The President of the United States has been accused of falsely leading the country into armed conflict. A special prosecutor believes recordings made of the President and advisors could hold evidence that the President was lying. The President refuses to surrender the tapes, saying they include sensitive information about American foreign policy on them. You are the Supreme Court: how do you rule? ii. Students need to be reminded of what they will be graded on in this Exit Ticket – Clearly identify for students what they will be graded upon in the exit Ticket (the summative assessment of this lesson). 1. Students will put serious thought and effort into each response – A large number of the responses on the Exit Ticket are open-ended, or opinion based. Because there is not necessarily “one right answer”, students need to show that they have put some time and thought into their responses. 2. Students used thoughts, opinions, or assertions from the seminar in their responses –Students need to use things they have gathered from the seminar in constructing their responses. This shows not only that they were paying attention during the seminar, but that they have been considering their classmates responses. 3. Student’s responses will be clear and well-written – Response to the written “Exit Ticket” will be well constructed, readable responses. This means complete sentences and thoughts. Ultimately, the teacher can determine whether or not he/she wants to grade for spelling, grammar, etc. In a class with heavy writing experience, a teacher might be more inclined to critically read for grammatical structure. In a class with little writing experience, more attention should be focused on the concept instead. Students who answer in bullet points, incomplete sentences, or show little-to-no structure in their response will not receive full credit. iii. Teacher Evaluation – Students will fill out a teacher evaluation form at the end of the lesson. This form is included with the rest of the materials. Remind students that it is in their best interest that they take the evaluation form seriously, so that you might better adapt your lessons to suit their personal needs. Resources: Teachers will need to be sure they have the following resources prior to teaching this lesson. Many of the worksheets and forms are included in the lesson plan. 1. Legal Brief for United States v Nixon (included) 2. Excerpts from the Supreme Court’s ruling in United States v Nixon (included) 3. Entrance Ticket (included) 4. Exit Ticket (included) 5. Teacher Evaluation Form (included) 6. Clip for “Nixon’s Apology” (link included, should be downloaded ahead of time) Adaptation: This lesson has been carefully designed to scaffold for students who might need more assistance with this lesson. Should a student with vision-impairment be part of the class, a teacher could provide the student with an audio recording of the brief and of the excerpts. For hearing-impaired students, a sign-language assistant might be needed to help the student understand what is being said. For students with reading difficulties, a teacher might want to assign the material to the student even earlier; perhaps even a week in advance. While the Brief is supposed to be relatively easy to read, the excerpts are very difficult for students not used to this wordy, complex writing. The seminar itself is scaffolded by allowing students who understood the material to help “translate” it to their classmates; the first questions are aimed at clarifying and summarizing the text. Hopefully, this will allow students who had more success with the material to clarify things for their classmates before we get into higherorder thinking questions. And if it becomes obvious that no student had success with the material on their own, the teacher can help guide them to understanding of the case before trying to application and analysis questions. Further, students can scaffold their own responses and explanations by answering clarifying questions asked by their own peers. This will allow students to expand explanations of basic concepts and ideas, and adapt their discussion to meet the needs of their fellow students. Differentiation: Socratic Seminars are difficult to differentiate. Most of the lesson is based around discussion. All students are given the opening questions prior to the lesson in order to inspire confidence and to give the conversation/discussion an easy start. For students with reading difficulties, or who simply require more preparation than most before speaking, some of the core questions can also be provided. Students who also are easily flustered during public speaking can “practice” with a teacher or another student prior to the actual seminar to get used to answering questions quickly and effectively. Should this be a general concern for the whole class, the teacher can use one or two questions on a day prior to the lesson to help students know what to expect. This could be a particularly good idea if few people in your class have participated in Socratic Seminars. There are ways to address non-auditory learners within the seminar. For example, having either a ticketless student, or the teacher him/herself, writing key themes, facts, ideas, arguments, or concepts up on the board/overhead projector might serve to help students who are more visual learners. Also, having an “official note taker” might help students who need more time with the material address the issue when writing answers on their exit ticket later. Important to differentiation is allowing students to ask questions during the seminar; anytime a student doesn’t understand a concept presented by a student, he/she needs to let fellow students know. This way, either the student or the teacher can try to explain the sentiment in another way that might help the student understand. Reflection: I feel this is going to be a fairly strong lesson. Again, it’s hard to tell with a Socratic Seminar until you actually get there and do it. The questions you’ve prepared may not work if the discussion goes a different way. Still, I believe that the questions I have prepared will assure that the students understand the case itself (what happened, what the ruling was, etc.), and the larger implications of that ruling. I also feel that this is a good topic for a Socratic Seminar; this case, in my opinion, requires a student to reflect, consider multiple view points, and conclude what it means for him/herself. Should the President have the authority suggested by the Nixon Administration? Is the power of Judicial Review too strong, capable itself of being easily corrupted? Are their cases where the President should be allowed to keep conversations secret? Or, as stated by the Wikileaks crowd, should all government information be available to the populace at all times? Or is it somewhere in the middle? I’ll admit to being a little hesitant because of the materials I used. I feel the Brief is too easy; it lays everything out for students without making them work too hard. Conversely, I feel the excerpts alone are too hard. If students combine the two, they should have a pretty thorough understanding of the material. However, knowing my class, I’m afraid many students would read the Brief (because it is simpler) and then just say they read the Excerpts (which are really the meat of the lesson). And while the brief might give them a very basic understanding, the “meat” of the seminar (the higher thinking) will require students to be familiar with the details of the court’s reasoning. The Brief lets students know what the courts ruled; the Excerpts help them understand why the courts ruled as they did. This is probably something a teacher needs to stress during the section where the importance of the text is explained. I feel I was able to do a good job with adaptation and differentiation, especially considering that this lesson is very “hands off” for the teacher. Sure, the teacher asks questions, but that’s about it. So the questions themselves must be scaffolded, and the teacher must make sure that all students have what they need to prepare for those questions. I like the way I scaffolded the questions; easier questions first to help students feel comfortable and confident, as well as to catch students up who had difficulties with the material. The more difficult questions, dealing directly with themes, concepts, and reflection, come only after I am sure students understood the basics of what they just read. As for the differentiation, I’ll admit that a lot of this deals with the teacher and individual students. Teachers will have to make sure that students have all that they need to be fully prepared, on time, to participate in the lesson. Teachers will also have to find ways (such as writing themes, ideas, and key facts up on the overhead) to help visual learners better understand what their classmates are saying. Teachers must also encourage students to ask questions of their classmates when they are confused, and must be prepared to step in to help clarify if too much time is being used up doing so. The writing section here isn’t too difficult; rather than focusing on larger essays about broad themes, the Entrance Ticket mostly makes sure that students will be prepared for the discussion and have a good understanding of the text. Students mostly use this ticket as a way to collect their thoughts and be sure they got all of the major themes and goals from the text. The exit ticket is more of a reflection, and makes sure that students can use what they got from the lesson plan and apply it in new ways. The exit ticket, while not as long or complex in terms of “writing” as some of my other papers, relies less on straight opinion and depends more a student truly understanding the lesson and the seminar. Ultimately, I think this is a strong lesson plan. Students will have a great deal to take from this, and a great deal to think about. Part of the “Exit Ticket” is a mini-simulation; students are asked to be SCOTUS Justices and to determine how they would rule on a similar, hypothetical case. Now, I don’t expect students to go directly to the Constitution; though I would be impressed by the deeper understanding of the SCOTUS’ job, I expect this to be more about students revealing how they personally feel about an issue. I feel that this is the ultimate goal of government classes, anyways: to get students to understand why they feel and think the way they do, and to reflect fully upon those thoughts in light of new information developed in class. More than anything else, Government is about developing democratic minds, and you can’t do that without embracing the individual. Legal Brief of United States v Nixon Facts of the Case The Watergate scandal occurred during the 1970s, resulting from the break-in of the Democratic National Committee headquarters at the Watergate office complex. A grand jury indicted seven of President Richard Nixon's closest aides in the Watergate affair. The special prosecutor appointed by Nixon sought audio tapes of conversations recorded by Nixon in the Oval Office. It was suspected that these audio tapes could contain confirmation that the President either knew of the break-ins and covered them up, or perhaps even ordered them himself. Nixon asserted that he was immune from the subpoena claiming "executive privilege.” Executive privilege is the right to withhold information from other government branches to preserve confidential communications within the executive branch, or to secure a national interest. Arguments Nixon: Because the President of the United States deals with sensitive, controversial information and issues every day, he has the right to keep records of his conversations secret from both the public and the court system. This is known as Executive Privilege. The court does not have the authority to review this Presidential power. United States: The right to Executive Privilege does not extend to virtual immunity from the criminal justice system. If the courts subpoena material not sensitive to the security of the country in the course of a criminal investigation, the President must surrender that material. Issue Is the President's right to safeguard certain information, using his "executive privilege" confidentiality power, entirely immune from judicial review? Ruling and Reasoning No. The Court held that there is no absolute, unqualified, presidential privilege. With the exception of some particularly high-security military and intelligence communications, the doctrine of separation of powers and the need for confidentiality in governance are not, by themselves, a justification for immunity from judicial review. The Court granted that there was a limited executive privilege in areas of military or diplomatic affairs, but said that the President must submit to "the fundamental demands of due process of law in the fair administration of justice." Therefore, the president must obey the subpoena and produce the tapes and documents. Results Nixon resigned shortly after the release of the tapes, after it became clear he was going to be impeached by the Congress. Nixon was later pardoned by President Gerald Ford. Information from this brief was obtained from the OYEZ Project. Excerpts from the Supreme Court’s ruling in United States v Nixon It is also recommended that you read this article near a dictionary of some kind, as some words aren’t easy to understand. It is recommended that you give yourself lots of time reading these excerpts, and do not try to read it all in one sitting. “Following indictment alleging violation of federal statutes by certain staff members of the White House and political supporters of the President, the Special Prosecutor filed a motion… for a subpoena duces tecum* for the production before trial of certain tapes and documents relating to precisely identified conversations and meetings between the President and others. The President, claiming executive privilege, filed a motion to quash the subpoena.” “The District Court thereafter issued an order for an in camera examination of the subpoenaed material, having rejected the President's contentions (a) that the dispute between him and the Special Prosecutor was nonjusticiable as an "intra-executive" conflict and (b) that the judiciary lacked authority to review the President's assertion of executive privilege. The court stayed its order pending appellate review, which the President then sought in the Court of Appeals.” “Although the courts will afford the utmost deference to Presidential acts in the performance of an Article II function, when a claim of Presidential privilege as to materials subpoenaed for use in a criminal trial is based, as it is here, not on the ground that military or diplomatic secrets are implicated, but merely on the ground of a generalized interest in confidentiality, the President's generalized assertion of privilege must yield to the demonstrated, specific need for evidence in a pending criminal trial and the fundamental demands of due process of law in the fair administration of criminal justice.” “Since a President's communications encompass a vastly wider range of sensitive material than would be true of an ordinary individual, the public interest requires that Presidential confidentiality be afforded the greatest protection consistent with the fair administration of justice, and the District Court has a heavy responsibility to ensure that material involving Presidential conversations irrelevant to or inadmissible in the criminal prosecution be accorded the high degree of respect due a President and that such material be returned under seal to its lawful custodian. Until released to the Special Prosecutor no in camera material is to be released to anyone.” “To read the Article II powers of the President as providing an absolute privilege as against a subpoena essential to enforcement of criminal statutes on no more than a generalized claim of the public interest in confidentiality of nonmilitary and nondiplomatic discussions would upset the constitutional balance of "a workable government" and gravely impair the role of the courts under Art. III.” “Since we conclude that the legitimate needs of the judicial process may outweigh Presidential privilege, it is necessary to resolve those competing interests in a manner that preserves the essential functions of each branch. The right and indeed the duty to resolve that question does not free the Judiciary from according high respect to the representations made on behalf of the President.” “In this case we must weigh the importance of the general privilege of confidentiality of Presidential communications in performance of the President's responsibilities against the inroads of such a privilege on the fair administration of criminal justice. The interest in preserving confidentiality is weighty indeed and entitled to great respect. However, we cannot conclude that advisers will be moved to temper the candor of their remarks by the infrequent occasions of disclosure because of the possibility that such conversations will be called for in the context of a criminal prosecution.” “We conclude that when the ground for asserting privilege as to subpoenaed materials sought for use in a criminal trial is based only on the generalized interest in confidentiality, it cannot prevail over the fundamental demands of due process of law in the fair administration of criminal justice. The generalized assertion of privilege must yield to the demonstrated, specific need for evidence in a pending criminal trial.” *Subpoena Duces Tecum - Ordering somebody to appear before the court and produce documents or other tangible evidence (papers, recordings, etc.) for use at a hearing or trial. United States v Nixon Seminar Entrance Ticket 1. What were the background events that lead up to this case? 2. What were the issues presented in this case? Why do you think these issues mattered? 3. What did the Supreme Court Rule? Why did it rule that way? 4. What is the American system of “Checks and Balances” in the United States Government? Can you give a few examples? 5. Do you think it is important for a President to be able to keep conversations between himself and advisors confidential? Are there any exceptions to your belief? 6. What happened immediately after the trial? What does this imply to you? Is this implication fair? United States v Nixon Seminar Exit Ticket 1. What did you contribute to the discussion? 2. What was the most interesting this you heard one of your classmates say? Why do you find it interesting? 3. What was something you didn’t know or understand coming into the seminar that you now have a better understanding of? 4. Explain why you agree or disagree with the Supreme Court’s decision. 5. Imagine this hypothetical situation: The President of the United States has been accused of falsely leading the country into armed conflict. A special prosecutor believes recordings made of the President and advisors could hold evidence that the President was lying. The President refuses to surrender the tapes, saying they include sensitive information about American foreign policy on them. You are the Supreme Court: how do you rule? Why? Teacher Evaluation: I’d like to get some feedback from you on how you think this lesson went. What were the strong points? What were the weak points? What would you do differently if you were teaching this class? Do you still have any questions about the subject material? Any other thoughts you’d like to add?