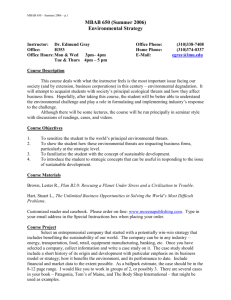

Dworkin on Unjust Law

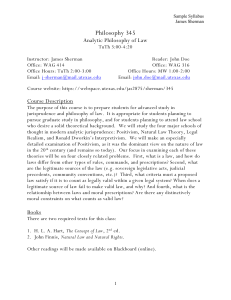

advertisement