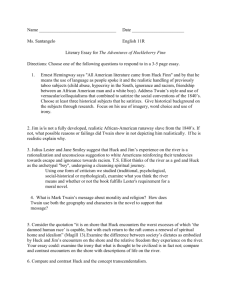

huck finn rides again: reverberations of mark

advertisement