Lecturer Guide 11

advertisement

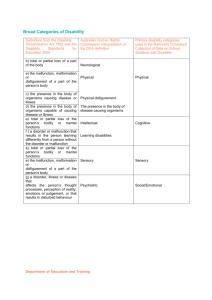

CHAPTER COMMENTARY The body may at first seem a fixed physical pre-given in social life, but this chapter demonstrates that it is profoundly subject to social processes and conditions: the impact of a changing world upon human physicality and the social technologies we adopt in making choices about our bodies. The example of anorexia and other eating disorders is located as a product of modernity, and a stark visual comparison is drawn between the anorectic starvation among plenty of a young Western woman and the starvation among famine within global plenty of a young African woman. This comparison shows that there are clear commonalities between scholars of health and those working on the sociology of the body. The complexity and fluidity of social life demands constant choices and the body has become part of the socialization of nature wherein what was once seen as ‘natural’ is now a social project on which individuals must work. The rise to dominance of the biomedical model of health is described, with its focus on bodies and disease entities rather than people in the round. The biomedical model developed medical practice as a tool for the rationalization and surveillance of the population. The main assumptions of the model are: the germ theory of disease; the separation of mind and body, rendering the patient as a sick body; that treatment lies in the hands of trained specialists capable of viewing the patient through the medical gaze and not with lay practitioners. The dominance of the biomedical model is linked with the transformation to modernity and the triumph of science and rationalization. The emergence of nation-states brings the idea of a population to be managed as an economic and military resource. Foucault has been influential in viewing modern medicine as part of a process of regulating and disciplining both individual bodies and the social body. The idea of ‘public health’ took shape as a way of eradicating pathologies from the social body. A whole range of institutions including hospitals, asylums prisons, schools and workhouses, developed as a means of regulating and controlling the population. Criticisms discussed include: the real causes of improved mortality and morbidity rates are environmental not medical; the patient as a person is negated by becoming a sick body; unscientific may not necessarily mean ‘bad’, and non-scientific approaches may have a contribution to make to health; the medical profession has spread its influence through the medicalization of normal experiences such as pregnancy, sadness and tiredness – this is further discussed through the example of the use of Ritalin to control hyperactivity in © Polity Press 2013 This file should be used solely for the purpose of review and must not be otherwise stored, duplicated, copied or sold Health, Illness and Disability children; the model has been open to gross political manipulation particularly in the area of ‘population policies’ the most extreme of which is eugenics. The rapid development of genetic medicine brings these issues to the forefront in contemporary life. It has also been suggested that biomedicine cannot cope with chronic and stress conditions. Hierarchical medical organization has created long waiting lists and complex referral procedures; concern over the harmful effects of medication and invasive surgery; the asymmetrical power relationship between patient and doctor; and, a religious or philosophical rejection of being treated as a body rather than holistically. Similarly, the expansion of both alternative medicine and complementary medicine is located as a manifestation of the processes of modernization which have promoted the notion of the individual in control as an informed consumer and the conditions which create but cannot cure the illnesses of modernity: insomnia, anxiety, stress and depression. In the West everyone is on a diet in so far as we constantly make choices about what to eat against a background of globalized food production, medical advice and social pressures to look young and be attractive. The example of diet is a useful one, as nearly all students will be willing to express an opinion and have stories to tell of weight reduction, ‘allergies’, medical or politically motivated diets. The emergence of HIV/AIDS in the 1980s is included as a counter to the general trend away from acute towards chronic conditions. The rapid transmission of HIV and enormous death toll of AIDS – some 25 million deaths worldwide – demonstrates that the modern assumption that most fatal diseases had been brought under control does not allow for the creation of new ones. The AIDS pandemic has certainly shaken people’s confidence in modern medical science to prevent disease. Health inequalities are also thrown into sharp relief by the distribution of HIV/AIDS cases, with developing countries suffering the most severe consequences. Next, the chapter turns to sociological perspectives on understanding health and illness. The normal functioning of the body is a taken-for-granted aspect of social life. Illness disrupts normal social life both for those who are ill and for people around them. Two sociological approaches to the experience of illness are identified: the functionalist work of Parsons on the sick role (a Classic Study) and interactionist approaches to the social meanings of illness. Three pillars of the sick role are identified. The sick person: (1) is not personally responsible for being sick; (2) is entitled to certain rights and privileges including a withdrawal from normal responsibilities; and (3) must work to regain health by consulting medical experts and agreeing to become a ‘patient’. Freidson argues that the sick role is modified in three ways depending upon the perceived legitimacy of the illness, the special privileges normally accorded to the ill being withheld from those with stigmatized illnesses. Goffman’s notion of stigma acting to disqualify stigmatized individuals from full social acceptance is useful in considering the reaction of medical professionals to members of stigmatized groups. Recent debates about the treatment of smokers, heavy drinkers and the obese could be considered here. The sick role models are criticized for failing to capture the lived complexity of illness. It is this complexity which interactionist studies of the management of the self through chronic illness have approached. Chronic illness involves daily processes of ‘illness work’, ‘everyday work’ and ‘biographical work’. Sociologists have studied how illness in such cases becomes incorporated into an individual’s personal biography as ‘lived experience’. Turning to the social basis of health, a range of data is presented demonstrating that the benefits of improved healthcare have not been evenly distributed throughout the 94 Health, Illness and Disability population; there are still considerable health inequalities. Social epidemiology studies the distribution of diseases. Figures are presented to support the conclusion that there is a clear class gradient to health. Materialist approaches are contrasted with cultural and behavioural explanations in the formation of policy. For example, the UK’s Black Report of 1980 offered a materialist analysis and called for a strong anti-poverty strategy as the key to improving health. Through the 1980s and most of the 1990s, government policy focused on highly individualized cultural and behavioural explanations. Our Healthier Nation, 1999, draws upon both material and cultural explanations, suggesting a series of joined-up initiatives to tackle different dimensions in the healthcare puzzle. Clear gender patterns in health are also noted: women live longer than men but are sicker and suffer more disability; men suffer more from violence and accidents and are more prone to substance dependency, while women are more likely to suffer from poverty. Doyal argues that women’s experience of health and illness is shaped by material disadvantage but also by their multiple roles in domestic work, employment, sexual reproduction, childbearing, mothering and regulating fertility. It is therefore necessary to consider the interaction between social, psychological and biological factors. Graham’s work on workingclass women suggests that many health problems are also related to their lack of social support mechanisms. Oakley’s work also stresses the need for social support to act as a buffer against the health consequences of the stress experienced by women. When looking at patterns concerning the relationship between ethnicity and health, it is more difficult to reach conclusions because, lacking any standard categories, it is hard to compare findings between studies, many of which fail to collect information on the probably significant factors of gender and class. Some illnesses are experienced more by individuals from African Caribbean and Asian backgrounds, only a limited proportion of which can be accounted for by inherited factors. Like explanations of class inequalities. some turn to cultural explanations such as diet and consanguinity to explain these patterns. Alternatively, social structural explanations include the over-concentration of members of ethnic minority groups in poor housing and hazardous and poorly paid work. The effects of both individual and institutional racism upon an individual’s health and patterns of healthcare for minority groups are also significant. In turning to health and social cohesion, the controversial argument that it is not the healthiest countries that are necessarily the richest, but those without extreme social inequalities and with high levels of social integration, is introduced and provides a link back to the thought of Durkheim. The work of Wilkinson has been influential in linking ill health to social inequalities and good health to better community cohesion. The conventional understanding of ‘disability’ has been challenged within the new field of disability studies. The language in which ‘disability’ is framed has provided a key site of political struggle. The individual model presents disability as a property of the individual who is presented as an ‘invalid’, suffering a personal tragedy, and who typically accepts the medical model of disability. In contrast, the social model of disability distinguishes between impairments and the disabling practices of society which prevent people with impairments from fully participating in social life. Shakespeare and Watson question the extent to which the social model can make invisible the experiences of impairment, which is to ignore a large part of people’s lives. Research has shown that many people with ‘impairments’ prefer to be identified as ‘ill’ rather than ‘disabled’. This is perhaps not surprising, as ‘disabled’ is a stigmatized identity. The example of Cherubism is presented as an example of the relationship between stigma and disability. 95 Health, Illness and Disability Whilst the impairment/disability distinction has been politically useful for disability rights campaigners, medical sociologists criticize the distinction, as both are social constructs; maintaining the distinction implicitly accepts the biomedical model. The UK Disability Discrimination Act (1995) and the 2010 Equality Act aim to protect disabled individuals against discrimination. The Acts defines a disabled person as ‘anyone with a physical or mental impairment, which has a substantial and long-term adverse effect upon their ability to carry out normal day-to-day activities’. Globally, it is estimated that there are over 1 billion disabled people in the world. Many disabilities in the developing world are caused by poverty. Poor sanitation and diet and a lack of medical care directly cause illness and disability: infections, injuries and dietary deficiencies left untreated can become chronic and disabling. TEACHING TOPICS The sociology of health and illness is a core theme in sociology teaching, at all levels. The material in this chapter will also be of particular interest to students following vocational courses in either health or social care and tutors will draw selectively upon it to support projects and topics within those vocational frameworks. 1. Health inequalities Inequalities in health exist between societies and within societies. This topic aims to explore the dimensions of these inequalities drawing on ‘The social basis of health’ and ‘The sociology of disability’, and aims to consider major conceptual frameworks within which health inequalities have been analysed. 2. Biomedicine and medical power The growth of biomedicine and the power of the medical profession are discussed throughout the chapter, and especially in the sections on ‘Sociological perspectives on medicine’ and ‘Sociological perspectives on health and illness’. This topic can also be linked to the example of the pelvic examination used in chapter 8. 3. Disability This is a very broad topic which focuses on the distinction between the individual and social models of disability, and encourages students to consider in very practical terms the ways in which society can be disabling. ACTIVITIES Activity 1: Health inequalities Numerous studies have detailed a strong and enduring relationship between social class and the prevalence of ill health. This statistical relationship is generally accepted as true, although some would argue the statistics are a product of the ways in which they are compiled and thus tell us little about health and a lot about how health professionals label both people and illnesses. Even among the majority who accept that the statistical relationship does tell us something real about the social distribution of ill health, there is no explanation of this pattern, which is universally accepted. Understanding the nature of this 96 Health, Illness and Disability relationship has very real political implications, as it is directly relevant to the formation of healthcare strategies and the allocation of healthcare resources. This then is an area where sociological interpretation and political preference become very difficult to disentangle. Materialist or environmental explanations and cultural and behavioural explanations are outlined on pages 457-60 of Sociology. A detailed analysis of these issues is offered by Sarah Nettleton in her book The Sociology of Health and Illness. She first considers the arguments about health statistics and then goes on to look at the other major types of explanation of inequalities in health: 2. Health selection explanations. This perspective argues that health status can influence social position. It is suggested that those who are healthy are more likely to be upwardly mobile, and those who are unhealthy more likely to ‘drift’ into lower social classes. … This account of social class differences has a social Darwinist – survival of the fittest – ring to it. But this is not an inherent feature of the approach. … [T]hose people who suffer ill health may well be discriminated against. … 3. Cultural or behavioural explanations. … [S]ocial class differences cause variations in health status, rather than vice versa. … Ways of living are presumed to vary between different social positions; in particular people in lower social classes indulge in more unhealthy behaviours, such as smoking, drinking alcohol, eating more fat and sugar, and taking less exercise. At one extreme, these lifestyle factors are seen to be in the control of the individual, and so it is up to the individual to alter his or her behaviour and nurture more healthy attitudes. At the other extreme, such behaviours are treated as being rooted in people’s social circumstances, but nevertheless remain, from this perspective, the main cause of social inequalities in health. … 4. Materialist explanations. This alternative social causation approach emphasizes the effects of social structure on health. In general this approach focuses on the impact of factors such as poverty, the distribution of income, unemployment, housing conditions, pollution and working conditions in both public and domestic spheres. … For example, when smoking and employment history are held constant, there still appears to be a relationship between poor housing and the presence of respiratory symptoms and heart disease. … Some argue that the cultural and material explanations can be conflated, pointing to the interaction between behavioural and structural factors, and suggest that it is more fruitful to try to find the right balance between them. Others … [argue that this] is unhelpful because although it intends to emphasize the social rootedness of lifestyles, such theorizing tends to discount any influence of the social and material environment that is not mediated through behavioural patterns. Thus intervention becomes reduced to developing culturally sensitive methods for encouraging changes in lifestyle and neglects the possibility of change in the environment. (Davy-Smith et al., 1990: 376) Indeed, this comment in many ways anticipates New Labour’s response to improving health, which emphasizes the importance of healthy lifestyles, albeit 97 Health, Illness and Disability acknowledging the context of social inequalities. (Sarah Nettleton, Sociology of Health and Illness (2nd edn), Cambridge: Polity, 2006, pp. 182–3) 1. What is the difference between a ‘social Darwinist’ and a ‘discrimination’ version of the health selection explanations? 2. The cultural or behavioural explanations are currently most popular among government policy-makers. What are the implications of these explanations for health policies? 3. If the materialist explanations are correct, what policies would be needed to tackle the structural factors they identify? 4. What information would you like to be able to decide between these competing explanations? Activity 2: Biomedicine and medical power A. Read the sections from Sociology on ‘Sociological perspectives on medicine’ and ‘Sociological perspectives on health and illness’. 1. What are the central assumptions of the biomedical model? 2. Which groups gain power through the biomedical model? 3. Who decides if a person can legitimately adopt the sick role? The French theorist Michel Foucault is discussed on pages 439 and 441-2. He has been very influential in recent studies of medicine and the body. His language is often quite florid and difficult to understand, but try thinking about this short quote: The body is directly involved in a political field; power relations have an immediate hold upon it; they invest it, mark it, train it, torture it, force it to carry out tasks, to perform ceremonies, to emit signs. (Discipline and Punish, p. 25) B. Read the ‘Using Your Sociological Imagination’ Box 11.1 on page 445, which tells the story of Jan Mason. Also read the section ‘Illness as lived experience’ on pages 453-6. 1. In what ways does the turn to alternative medicine reflect a shift in the power relations of the body? 2. How are those with chronic fatigue viewed by the medical gaze? 3. Why might someone with chronic fatigue syndrome prefer the identity ‘ill’ to ‘disabled’? Activity 3: Disability Read the section ‘The sociology of disability’. The Disability Discrimination Act, Part 4, places duties on educational institutions to ‘make reasonable adjustments’ to ensure that students are not disadvantaged because of disability. ‘Reasonable’ is defined as: consistent with academic standards, affordable, practical, not adversely affecting other students and consistent with health and safety legislation. Since September 2005, all buildings and facilities must be physically accessible to disabled students. 98 Health, Illness and Disability In principle, although institutions will need to react to the particular needs of individual students, adjustments should be made proactively to create enabling rather than disabling environments for all students. While you read the following description of a college, think about the kinds of ‘reasonable adjustments’ the institution can make: The students who use County College are generally happy there. It’s quite a small college (1,500 students) and is seen as friendly and supportive place to work and study. The college buildings are a mixture of: Victorian red-brick, neo-gothic, with a grand central staircase and smaller back stairs which lead to staff offices on the upper floors; some early 1970s blocks of teaching rooms and formal lecture halls with fixed seating and writing ledges; and ‘the huts’, temporary classrooms located across the car park and grassed areas. All of these buildings have their own particular problems. The Victorian building fronts onto a busy road and in the summer there is a trade-off between stifling heat and the traffic noise which comes in when the windows are open. The 1970s block was designed at a time when seminar groups were quite small and large lectures were very formally delivered from the front of the lecture hall with only chalk-boards as visual aids. As a result, the classrooms tend to be overcrowded on the rare occasions when all of the students turn up and attempts at involving students in discussion in the lectures difficult. The ‘huts’ also suffer from heat and noise fluctuations and are notorious for their broken, missing and sticking blinds which make some rooms very bright on summer days and others very gloomy in the winter. The timetable is a source of complaint as people have to get from one side of the campus to the other in literally no time at all and are sometimes timetabled for three hours without a break. The staff use an interesting mix of teaching styles. Lectures are generally supported with OHPs or Powerpoint presentations and quite a few staff make use of video clips. All of the courses have course handbooks which outline the lecture and seminar programmes and provide reading lists that include books, journal articles and relevant website addresses. A lot of seminars include small group work and role play. There is a Virtual Learning Environment where handbooks, lecture notes and other backup resources are located and through which students can take part in on-line conferences and submit their coursework electronically. The library and learning resource area is wifi enabled. 1. How might this campus disable students with mobility impairments? 2. What difficulties might this campus present for students with different levels of sight and hearing impairment? 3. What reasonable adjustments might the college make to enable students with diabetes or chronic breathing difficulties? 4. What reasonable adjustments will lecturers need to consider in order that their lectures, seminars and resources are equally accessible to all students? 5. In what ways does the Disability Discrimination Act utilize a social model of disability? REFLECTION & DISCUSSION QUESTIONS Health inequalities Should health be the responsibility of the individual or of society as a whole? 99 Health, Illness and Disability What would be the results if unhealthy foods were to be taxed? How could access to healthcare for disadvantaged groups be improved? As the demand for healthcare is infinite, it is a scarce resource which has to be rationed – but on what basis? Biomedicine and medical power Do alternative and complementary medical practitioners use the medical gaze? Are patient/doctor power relationships dismantled in alternative medical approaches? Why are social phenomena medicalized? What does it mean to say that medical treatment is a social technology? Disability Is the language we use to talk about disability really important? How do you draw a line between illness, disability and impairment? What are the limits of ‘reasonable adjustments’ in educational settings? Should people with facial disfigurement undergo surgery to ‘fit in’ more easily? ESSAY QUESTIONS 1. ‘The way to tackle ill health is to first tackle poverty’. Explain and discuss this view. 2. Why are people in the West rejecting biomedicine? 3. Is disability a feature of society or the individual? MAKING CONNECTIONS Health inequalities There are links to issues of inequality across the whole book. Chapter 12 on stratification and Chapter 13 on poverty both link strongly to this topic, and a global dimension can be found in Chapter 14. Inequalities in terms of gender (Chapter 15) and ethnicity (Chapter 16) are also relevant. Biomedicine and medical power This links directly to the management of self-identity and self-presentation discussed in Chapter 8 and to Durkheim on social solidarity in Chapter 1 and Foucault in Chapter 3. Disability This topic is a useful comparator in the exploration of other forms of discrimination and inequality. The discussion of prejudice and discrimination in Chapter 16 can be applied in this context. The constructionist emphasis on the language of disability can also be linked to ideas of ageing in Chapter 8. 100 Health, Illness and Disability SAMPLE SESSION Health inequalities Aims To introduce and illustrate a range of accounts of inequalities in health. To link sociological research to current debates in health policy. Outcome: By the end of this session students will be able to: 1. Describe two broad types of explanation for inequalities in health. 2. Identify an electronic source for government information on health. 3. Apply explanations of health inequalities to the analysis of an aspect of current health policy. Preparatory tasks 1. Read and make notes on the section ‘The social basis of health’ 2. Locate and read the summary of Choosing Health (2004) on the Department of Health website: www.dh.gov.uk 3. From the same site identify a recent press release which announces a new policy initiative, print off a copy and bring it to class. Classroom activities 1. Tutor-led whole group session reviewing the explanations identified in the section, ‘the social basis of health’ and the key recommendations of Choosing Health. (10 minutes) 2. Tutor-led feedback from group on the recent policy initiatives they have identified. (10 minutes) 3. Split group into two. Each group to be given two or three of the recent press releases. Group A to analyse them from a cultural and behavioural position and Group B from a materialist position. (25 minutes) 4. Brief feedback from the groups. (10 minutes) Assessment task In groups of 3 or 4, prepare press releases for two new health policies: one which would be supported by a cultural and behavioural analysis of health inequality and one by a materialist analysis. Write a brief (300 word) statement saying which is which and why. 101