heat & mass transfer - Department of Materials Science and Metallurgy

advertisement

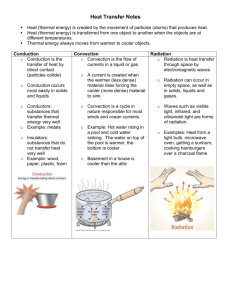

II Natural Sciences Tripos Part II MATERIALS SCIENCE C17: Heat and Mass Transfer Vapour Transport of ZnS under temperature gradient from the hot end (on the right) at 1753K, condensing at the cold end (on the left) at 1473K Name............................. College.......................... Dr R. V. Kumar Easter Term 2014-15 2014 15 C17 - HEAT & MASS TRANSFER Dr R.V. KUMAR COURSE CONTENT (6 Lectures + 1 Examples Class) Heat Transfer Basic concepts of heat transfer by conduction, convection and thermal radiation and their relevance to metallurgical processes Heat conduction equation; convection and heat transfer calculations; thermal resistance; heat transfer coefficient; selected dimensionless groups; radiation from black and grey surfaces Case studies: Combined modes of heat transfer in (a) induction heating (b) plasma spraying and ( c) stream shrouding in continuous casting Mass Transfer Fluid flow and viscosity; mass transfer in metallurgical processes; mass transfer coefficient and inter-phase mass transfer Case studies: Applications of mass transfer calculations to (a) gas dissolution in molten metals and (b) metal refining reactions Examples Class (one); Question Sheet (one) Book-List 1. J.P. Holman, Heat Transfer, 8th Edition, McGraw-Hill, 1997 (Cf 12) 2. W.J. Beek, K.M.K. Muttzal, J.W. Van Heuven, Transport Phenomena, John-Wiley & Sons, 1999 (Cf 13) 3. E.T Turkdogan, Fundamentals of Steelmaking, The Institute of Materials, 1996, Ch. 2. (Dg 153) 4. G.H. Geiger and D.R. Poirier, Transport Phenomena in Metallurgy, Addison-Wesley, 1973. (D 23) 1 HEAT TRANSFER - BASIC CONCEPTS Heat transfer is energy transfer due to a temperature difference; Heat transfer occurs whenever: there is a temperature gradient within a material there is temperature difference between a material and its surrounding two bodies at different temperatures are brought together Everyday examples of heat transfer: naturally occurring such as solar energy transfer to earth specially engineered as in melting of materials using fuel or electrical form of heating Often the heat transfer is intentional and therefore equipment and materials are designed to facilitate heat transfer. Sometimes heat transfer is not desired, such as in minimising heat losses from a furnace, when insulating materials are suitably provided. Regardless of the mechanism or mode of heat transfer the driving force for heat transfer is always temperature difference. The Laws of Thermodynamics help us to evaluate the amount of heat transferred (The First Law - Conservation of Energy) and the direction of heat transfer (The Second Law - increase in Entropy for heat flow from higher to lower temperature), but is not concerned with the rate at which a heat transfer process takes place or with the manner in which it take place. The rate and the mode of heat transfer is the province of “heat transfer” studies. 2 Modes of Heat Transfer There are 3 modes of heat transfer: Conduction, Convection and Thermal Radiation and the rate at which heat is transferred depends on the mode of transfer. These modes can be best illustrated by considering heat transfer between two flat plates, each of area 1 m2, facing each other at a distance 5 cm apart. The hot plate is maintained at a steady temperature of 80oC and the cold plate at 20oC. Space for sketching: For a perfect vacuum between the plates, heat can only be transferred by Thermal Radiation, which involves propagation of energy through space at the speed of light, by electromagnetic phenomena similar to light and radio wave propagation. Thermal radiation does not require the presence of matter for its propagation, although it can be transferred through gases. 3 If a solid material such as copper is placed between the plates in perfect contact, then heat is transferred by Conduction. In solids, heat conduction involves transfer of energy by (a) vibrations through the lattice structure of the solid and/or (b) free electrons. Good electrical conductors like copper are also good heat conductors. In liquids, heat conduction involves atomic vibration and free electron movement as in solids, together with some translational movements of ions/atoms. In gases, where atoms/ molecules are far apart from each other, heat conduction is governed by the rate at which the kinetic energy of gas molecules can be transferred by random collisions, and therefore is a slow process. In the above example, if solid copper is replaced by mineral wool, which is essentially a composite of air pockets trapped in wool fibres, heat conduction is dramatically reduced. Although heat conduction through a gas is a slow process, if the plates were separated by air alone, heat transfer would be higher than as expected from conduction alone. This is because, air does not remain stationary. Due to motion of fluid past the surfaces, heat transfer takes place by Convection. Convection heat transfer is a mixture of conduction and bulk movement of the fluid. Conduction takes place across a thin boundary layer of fluid 4 close to the surface. Fluid flow will arise by Natural Convection i.e. density difference between air near the hot surface and air near the cool surface. Hotter part of air will rise vertically upwards due to a buoyancy effect and the cooled air near the cold plate will descend. The exact amount of heat transferred will depend upon the properties of the fluid. Also note that free radiation will occur irrespective of convection in gases. If air is replaced by water, the heat transfer increases by two orders of magnitude in this example. If air at 20oC is physically blown past the hot surface, the convective heat transfer is termed Forced Convection. In reality, it is impossible to separate or isolate entirely one mode from the others. However, for simplicity of analysis, we will consider each mode separately. 5 CONDUCTION Fourier’s First Law (for steady state heat conduction) L T1 T2 →Q Q = -kA T/x, or q = -k T/x = k (T1 - T2)/L Q = Rate of heat transfer by conduction (W) q = Rate of heat transfer per unit area (W m-2) k = thermal conductivity of the material (W m-1 K -1) A = surface area; L = Length Typical values of k (in (W m-1 K -1) diamond: 3000 metals: 390 (copper); 15 (stainless steel) insulators: 1 (firebrick); 0.048 (mineral wool) liquids: 0.6 (water); 0.07 (Freon 12) gases: (at P =1 atm); 0.18 (hydrogen); 0.026 (air) - measuring “k” is a good way of detecting hydrogen in air. Heat conduction in a solid is influenced by the amount of heat transferred by convection (natural or forced) at the surface. Space for sketching: Heat transfer rate to the surface of the solid per unit area: q = h(T - Ts), where h = heat transfer coefficient (W m-2 K-1) h = f (fluid property, velocity of fluid) 6 One-Dimensional Steady-State Conduction: For example, for conduction through a solid slab or a cylinder maintained at T(x =0) = T1 and T(x=L) = T2, it can be shown that rate of heat flow: Q (Watts) = qA = kA T/L, where T = T1 - T2 and A = surface area. Using electrical analogy, I (amp or C/s) = V(volts) / R(ohms), the concept of thermal resistance can be developed. Therefore: Q(W ) T ( K ) / Rth ( K / W ) where the Thermal Resistance Rth for the slab = L/Ak. Thermal resistance can be defined for the various situations, (e.g. thermal resistance for convection at a surface is 1/hA), and the corresponding electrical analogue readily described. 7 Composite Media: Consider a simple series made up of two different materials as will be described. Also consider convective heat transfer at the two outer surfaces of the composite wall thus adding up to 4 thermal components. At steady-state, the unidirectional heat flux through the four parts of the entire circuit is constant. Thus: Q Ahi (Ti T1 ) k1 A(T1 T2 ) k 2 A(T2 T3 ) Aho (T3 To ) L1 L2 The problem is greatly simplified by making use of the concept of thermal resistance. The four thermal resistance are in series and the Rtotal = total resistance for the whole circuit is simply their sum = Ri + R12 + R23 + Ro And the heat flow is: Q = Ti - To/ Rtotal. We need to know the total temperature drop across the system to calculate the heat flux which we can use to determine the temperature at any position within the composite wall. Space for sketching: 8 The General Heat Conduction Equation: It is a mathematical expression of the principle of energy conservation in a solid substance, derived using a specified control volume of the material in which heat transfer occurs by conduction only (similar in concept for diffusion of matter). For simplicity, we will consider 1-D heat conduction along x-direction, but also include the possibility of thermal energy generation within the material itself. Energy balance for a control volume: Thermal conduction into the left face + thermal energy generated within control volume = thermal conduction out of the right face + changes in internal energy of control volume, i.e. storage of thermal energy, the heat conduction equation (Fourier’s 2nd Law) can be derived: Terms: g = rate of thermal energy generation internally per unit volume; = density; c= specific heat; k = thermal conductivity of the material; these three material properties are combined to define the “thermal diffusivity of the material: = k/c (in m2 s-1) and is associated with the diffusion of thermal energy into the material during changes of temperature T with time t. Space for Derivation: 9 Fourier’s 2nd law of heat conduction: 2T/x2 + g/k = (c/k) T/t = 1/ T/t Typical values of (m2 s-1) x 106 at 300K: Copper - 114; Lead - 25; Steel - 12; Bricks - 0.5; Water - 0.13; Air - 0.3. Boundary and Initial Conditions: The heat conduction equation requires specifying one initial condition (e.g. distribution of temperature at t =0) and 2 boundary conditions (for each co-ordinate), which specify the thermal conditions at the boundary surfaces. Initial condition: T(x, t=0) = Ti For example, at a boundary surface, one of the following may be specified: the temperature (boundary condition of the 1st kind) the heat flux (boundary condition of the 2nd kind) heat transfer by convection into the surrounding fluid at a specified temperature (boundary condition of the 3rd kind) Examples: B.C. of the 1st Kind: A surface maintained at a constant temperature; T (0, t) = To at the interface between a wax candle and the flame; or the liquid/solid interface in a welding pool (moving boundary) 10 B.C. of the 2nd Kind: A fixed value of heat flux at a boundary, i.e. q is constant; -q/k = dT/dx (x=0, t) = constant; (slope of T vs x is constant at x=0) Under special condition, if dT/dx = 0 i.e. q =0, then it is called “homogenous boundary condition of the 2nd kind” and the boundary is described as an “adiabatic boundary” This situation may be approximated in sand mould casting of a liquid metal where the thermal conductivity of sand is very low compared with that of the metal and all the heat flow is in the vertical (y) direction. Heat transfer into the insulating mould is considered to be zero: dT/dx (x =0, t) = 0. B.C. of the 3rd Kind: Convective heat transfer into a fluid at a fixed temperature T ; Therefore heat balance at the boundary is achieved when heat transfer by conduction = heat transfer by convection; q = -k dT/dx (x =0) = h (Ts - T) 11 Heat Transfer Solutions One-D heat conduction equation in the radial direction (cylindrical coordinates) 2T/r2 + 1/r(T/r) + g /k = 1/ (T/t) One-D heat conduction equation in the radial direction (spherical coordinates) 1/r2 (r2 T/r)/r + g /k = 1/ (T/t) An example of how cylindrical co-ordinates can be used to solve steady state radial flow: Long Hollow Cylinder: For steady radial flow of heat through the wall of a hollow cylinder as shown below, cylindrical co-ordinates are convenient. Since in this case the temperature depends only on the radial co-ordinate, the equation is: 1 d (rdT / dr ) 0 r dr The boundary conditions are: T (r1) = T1 and It can be shown that the thermal resistance is Rcyl Space for sketch: 12 T (r2) = T2 ln( r2 / r1 ) 2kL Space for Derivation: 13 Solution for Unsteady-State Heat Conduction Problems: Let us consider heat transfer by conduction in solids, in which the temperature varies not only with position in space, but also undergoes a continuous change with time at any position described by the partial differential equation: T = 2 T t x2 The initial condition: T(x, 0) = Ti (uniform) The boundary conditions: T(0, t) = To and T(, t) = Ti T To Ti x For a flat semi-infinite plate or slab, the form is identical to the diffusion equation, and the solution is of the same form: T(x,t) = To + (Ti - To) erf (x/ 2 t) It can be shown that when x = 4 (t)0.5, T = Ti which imply that no penetration of heat at such values of x and t for a given . At x = (t)0.5, T = ½ (To + Ti). The following table illustrates these points clearly: Copper (= 114 x 10-6 m2/s) Glass ((=0.6x10-6 m2/s) Time, t 1s 1hr 1s 1hr Distance, x 43 mm 2.6 m 3.1 mm 0.19 m 14 Dimensionless Parameters: The expression x/(t)0.5, is a useful expression for estimating the extent of heat penetration by conduction. The inverse of the square of this parameter is defined as the Fourier Number (Fo) = t/L2 Another useful dimensionless number called Biot Number (Bi) is defined as the ratio of convective heat transfer and conductive heat transfer at the surface of a solid: Bi = hL/k (where h = convective heat transfer coefficient at the surface, k = thermal conductivity of the solid and L = characteristic length of conduction) In the semi-infinite slab problem discussed above, the temperature at the surface is maintained at a constant value, a situation that can be described as akin to h → . For a situation, where k is very large in relation to h i.e. k → . Therefore, Bi → 0. For heat transfer situations, where the Biot number is small (Bi ≤ 0.1), the heat transfer is limited only by convection. 15 Newtonian Heating or Cooling (Lumped Systems) When a flat plate is cooled from an initial uniform temperature of Ti by a fluid at temperature Tf, the temperature distribution, which varies with time, as shown below, can be described by the transient heat conduction solution. For Bi ≤ 0.1, the temperature gradients within the plate are negligible, and the temperature of the whole plate varies only as a function of time. Such a process of cooling (or heating) is called “Newtonian”. Space for sketching: Rate of Heat lost by convection during cooling = Rate of decrease of internal energy hA(T - Tf) = - VCP dT/dt where V = volume of the plate and A = area of the plate exposed to the fluid. By rearranging and integrating, it can be derived that T Tf Ti T f exp( hAt ) VC p In deriving the above expression, although A and V are specified, no geometrical restrictions have been imposed; also note that the solution does not contain the conductivity of the material. 16 CONVECTION We have seen how convection can provide a possible boundary condition for conduction problems in the form of a heat transfer coefficient, h. In dealing with heat transfer by convection, i.e. energy transport between fluids and surfaces, we are mainly concerned with obtaining the value of h, for various systems and investigating how the heat transfer coefficient varies as a function of the fluid’s properties, such as thermal conductivity, viscosity, density and specific heat, the system geometry, the flow velocity and the temperature differences. 17 Fluid motion is the distinguishing feature of heat transfer by convection. In free convection heat transfer, the fluid motion arises solely due to a local fluid buoyancy difference caused by temperature difference. In forced convection heat transfer, the fluid motion is caused by imposition of a pressure difference by using a pump or a fan. Flow in pipes, ducts, nozzles ad heat exchangers etc., are examples of internal flow, where the flow is bounded by solid surfaces apart from an inlet and outlet. If the fluid experiences only one solid boundary, such as fluid flow past a flat plate or a cylinder, the flow is deemed an external flow. The fluid exerts a drag force on the surface as a result of viscous action, which affects the convective heat transfer. These effects must be considered to analyse heat transfer. Forced Convection (External Flow): Consider flow of a fluid over a flat plate; Space for sketching: When fluid particles make contact with the surface of the plate, they assume zero velocity, which act to retard motion of molecules in the adjoining fluid layer, resulting in a viscous effect, until at a distance y = , from the surface when the effect is negligible. And further at x = 0, at the leading edge, = 0 (no viscous effects) and at x =L, = max (maximum viscous effects) 18 These viscous forces are described in terms of shear stress between the fluid layers. For many fluids, the shear stress is proportional to the velocity normal gradient: = du/dy The constant of proportionality is called as the dynamic viscosity, (N.s m-2) or (Pa.s); fluids which satisfy this equation are called Newtonian fluid. The region affected by the viscous force is called the “boundary layer” and = boundary layer thickness. When viscous forces are dominant, the flow tends to be streamlined (called laminar) and the fluids flow along flow lines which do not touch each other, i.e. there is no cross flow. When inertial forces dominate over viscous forces, the regularity is disturbed, and a transition to turbulent flow is observed, where regions of fluid can move to and fro across streamline. For the above situation, Re is defined as a function of x, f(x): Rex = u x / (at location x) Often simplified to Rex = u x / where is the kinematic viscosity = / = dynamic viscosity/density For fluid flow, Reynolds number (Re), which is dimensionless number represents the ratio of inertial force / viscous force: Re = uL/ (where u = velocity of the fluid, L = characteristic dimension of the flow geometry. Reynolds number (Re) provides a criteria for determining whether the flow is laminar (streamlined) or turbulent (erratic). In general, high velocity, high fluid density and low fluid viscosity promote turbulent flow. Space for sketching: Laminar Flow Turbulent Flow 19 Flat Plate: The start of transition from laminar to turbulent flow over a flat plate has been found to be at Rex > 5 x 10 5. This is satisfied at x = xc - the critical distance from the leading edge. Space for sketching: 20 Dimensionless Parameters: Since a large number of variables are involved in calculating the values of heat transfer coefficient (and for mass transfer coefficients as we shall see later), the coefficients are frequently reported as correlation’s of dimensionless numbers. We have already considered the dimensionless numbers Fo and Bi and defined their physical significance. If all the variables can be identified, which are sufficient to specify a given heat (or mass) transfer situation, then it is possible to obtain pertinent “Dimensionless Groups” without any reference to the basic differential equations at all. There is in fact a systematic way of determining the logical groupings of the pertinent variables in the form of dimensionless parameters by using a technique called the Buckingham pi theorem. The dimensionless numbers themselves have important physical significance. The correlation between the different dimensionless groups for a given heat transfer situation will allow us to calculate the value of h, the heat transfer coefficient. 21 Space for deriving Dimensionless Parameters: 22 Thermal Boundary Layer: If the fluid stream has a temperature different from solid surface, then a thermal boundary layer analogous to the concept of the velocity boundary layer will also develop. Consider a fluid at a uniform temperature T at the leading edge flowing past a flat plate which is maintained at a constant temperature Ts: Space for sketching: At x = 0, the T (y) = T. At the surface of the plate, the fluid particles achieve the same temperature as the plate’s surface (thermal equilibrium is assumed). Temperature gradients (T/y) which is a function of x, develop as shown in the figure above. The region of the fluid in which the temperature gradients exist is referred to as the thermal boundary layer (t). At any distance x, from the leading edge, the local heat flux at the surface of the plate (y=0) is given by: qx = -kf (T/y)y=0 where, kf is thermal conductivity of the fluid. Since there is no fluid motion at the surface of the flat plate, the Fourier’s First law can be used. The heat flux at the surface can also be written in terms of heat transfer coefficient, h. qx = hx (Ts - T) Therefore, the local heat transfer coefficient hx = -kf (T/y)y=0 / (Ts - T) A good estimate of hx can be shown kf/t. The mean heat transfer coefficient, for the whole surface can be obtained by integrating the above equation over the distance x = 0 to x = L along the flat surface. h = 1/L hx dx 23 Heat Transfer with Laminar Forced Convection over a Flat Plate: From the above discussions it is clear that convective heat transfer over a surface involves both momentum transfer coupled with energy transfer. For any given condition of velocity profile, it is the relative magnitude of / which determines the magnitude of convective heat transfer. Correlations between three important dimensionless (empirically obtained) numbers can be used to estimate the value of heat transfer coefficient. Reynolds number (Rex ) = inertial forces/viscous forces = u x / Prandtl number (Pr) = momentum diffusivity /thermal diffusivity = / Nusselt number (Nux) = total heat transfer/conductive heat transfer = hxx/kf In general for forced convection: Nu = f (Re, Pr). Also note that all the fluid properties, e.g. , and kf are evaluated at a mean boundary layer temperature, called the film temperature given by: Tfilm = 0.5(Ts + T). A local value (at any x) for a given parameter is defined by using a subscript: as hx, Rex, Nux etc., while the average value (integrated over all x and then divided by L) over the surface is defined by dropping the subscript as h, Re or Nu respectively. 24 The correlation for laminar flow over a flat plate is given by: (for 0.6 = Pr = 50; Re < 5 x 105) local Nusselt number: (Nux) = 0.332 Pr1/3 Rex (Nux) = hxx/kf Nu (for average h over the plate length, L) = 0.664 Pr1/3 Re = hL/kf Where Re = ReL For turbulent flow over a flat plate: 5 x 105 < Re < 107; 0.6 < Pr < 60 Nu (for average h over the plate length, L) = 0.037 Pr1/3 Re0.8 For heat transfer to a sphere of dia, d (laminar flow): 2 < Re < 200 Nu = 2 + 0.6 Pr1/3 Red 25 FREE CONVECTION HEAT TRANSFER: In forced convection, the fluid flows as a result of an external force resulting in a known velocity distribution which can be used in the energy/momentum equation. Convection may be induced by difference in density across the flow resulting in buoyancy. Consider a hot vertical plate placed in a body of fluid at rest. (Space for sketching): Temperature variation within the fluid will generate a density gradient, which will give rise to convective motion due to buoyancy forces. The momentum and the energy equations still contain velocities terms, but these are not knowable and hence the situation is more complex. Generally, the rate of mixing is lower than in forced convection, and therefore the h values are lower. Heat transfer by free convection is a very important mode of heat transfer in several practical situations such as: in electrical and electronic engineering applications in the cooling of electrical components; in the heating of a room by central heating system with radiators. Typical Values of Heat Transfer Coefficient, h (W m-2 K-1) Natural Convection: Gases: 2-30 Liquids: 50-1000 Forced Convection: Gases: 6-600 Water: 200-17000 Boiling Water: 3000 - 60000 Condensation: 6000 - 120000 An exact evaluation of h for free convection is very complicated. Empirical Correlations used to evaluate h, require the introduction of another dimensionless parameter called Grashof number (Gr): Gr = buoyancy force / viscous force = g (Ts - T)L3 / 2 For free convection, the Nusselt number is correlated as: Nu = f(Gr, Pr) As with forced convection, all fluid properties are evaluated at the film temperature: Tfilm = 0.5(Ts + T). 26 Natural or Free Convection over a Vertical Plate (for Laminar condition) Nu = (GrL/4)-0.25 0.902 Pr (0.861 +Pr)0.25 4 (10 < GrLPr < 109) Natural or Free Convection over a Vertical Plate (for Turbulent condition) Nu = 0.0246 GrL2/5 Pr7/15 (1 + 0.494 Pr2/3)-2/5 (109 < GrLPr < 1012) Space for sketching: Hot Vertical Plate Cold vertical plate 27 THERMAL RADIATION Thermal radiation is electromagnetic energy in transport which can travel through empty space and originates from a body because of its temperature. The rate at which energy is emitted depends on the substance itself, its surface condition and its surface temperature. Thus radiation heat transfer is the result of interchange between various surfaces or bodies. The emission is in the form of electromagnetic waves travelling in straight lines with wavelengths 0.1 to 100 m, covering a significant part of UV, all of the visible and most of the IR spectrum. A perfect emitter or absorber against which the radiation properties are compared is called a “black body” (a hypothetical ideal surface). The radiation emitted by a black body varies continuously with and increases with temperature. The maximum emissions are achieved at shorter wavelengths as temperature is increased. Space for sketching: The total rate of emission at any particular temperature is found by summing the radiation over all wavelengths (area under the curve of E vs ) eb = T4 (Stefan-Boltzmann Law), where = Stefan-Boltzmann Constant = 5.67 x 10-8 W m-2 K-4 28 Any real body emitting thermal radiation has a total emitting power which is some fraction of the emissive power of a black radiator, which is defined as the emissivity of the material (): e = eb The emissivity of a typical real body varies with wavelength and the variation can be quite irregular. Frequently, it is assumed that the emissivity of a surface does not vary with wavelength. Such a surface is known as a grey surface. Any incoming radiation can be absorbed, reflected or transmitted by a given material. If we define the total irradiation, G, of a material as the flux of thermal radiant energy incoming to the surface and the total radiosity, J as the total flux of radiant energy leaving the surface of the body (energy emitted + energy reflected), then: G = G + G + G or + + = 1 where = absorptivity (fraction of G absorbed) = 1 for a black body; = reflectivity (fraction of G reflected); and = transmittivity (fraction of G transmitted) = 0 for opaque materials. J = e + G Space for sketching: Imagine a region in space completely filled with black body radiation. A real body 1 emitting radiation at a rate e1 is placed in this region; the net rate of energy transferred from the body is q = e1 - 1eb = energy emitted - energy absorbed = 1eb - 1eb If the body is in thermal equilibrium with the black body radiation, then q = 0, and 1 = 1 Thus the emissivity and absorptivity of any body at thermal equilibrium are equal. 29 A cavity with a small aperture is the closest approximation in practice to a black body. Since radiation entering the cavity is subject to repeated partial absorption and reflection, the effective absorptivity of the cavity to the external radiation is unity. (space for sketching): The energy emitted from any point on the walls of the enclosure is eb; when this radiation strikes other parts of the enclosure, a certain fraction equal to eb is reflected. A second reflection equals (eb), while the third one is (eb). Since the hole is assumed to be very small, radiation that can escape is neglected, and thus the radiation is therefore made up of infinite number of such reflections. Therefore, e (hole) = eb ( 1 + + 2 + 3 + ……) or e (hole) = eb ( 1/1-) Since = 1 - , and = (thermal equilibrium), e (hole) = eb. Radiation from a cavity is therefore very nearly black. If the walls are maintained at temperature T, the emissive power from the cavity is = T4. A radiation standard can be constructed with heavy metal internal walls that are made rough and oxidised to increase emissive power. The walls can be heated electrically, while the exterior is well insulated. 30 Radiation Combined with Convection: At very high temperatures, as radiant energy depends upon the fourth power of temperature, can completely dominate over convection. In many practical situations at intermediate temperatures, both modes of energy transport must be considered. The total heat flow is the sum of the convective and the radiant heat flow. It is often convenient to use the total heat transfer coefficient, ht = h + hr where the radiant heat transfer coefficient hr = q / (T1 - T2) = 1 (T14- T24) / (T1 - T2) corresponding to a situation where surface 1 is surrounded by or exposed only to some fluid at a bulk temperature T2. 31 MASS TRANSFER Mass Transfer Coefficient: Analogous to heat transfer coefficient, the mass transfer coefficient can be defined for transport of mass at the interface of two phases as flux of component A divided by concentration difference: k M J M (C Ao C ) Mass transfer coefficient has both diffusional and bulk flow contribution. In analogy with Heat Transfer, we can define Dimensionless Numbers to evaluate mass transfer coefficients for different situations. The Sherwood Number (Sh) has the same or similar functional dependence on the Reynolds (Re) and Schmidt (Sc) Numbers as the Nusselt does to Reynolds and Prandtl Numbers. Sherwood Number: Shx = kM x/D = Total mass transfer/Diffusive mass transfer Schmidt Number: Sc = /D = Momentum diffusivity / Mass diffusivity Sh = f (Re, Sc) from the functional dependence, we can calculate the value of kM Space for sketching: 32 Laminar flow along a flat plate: Sh = 0.323 (Re)1/2 (Sc)1/3 for Re < 5 x 105 Laminar flow through a circular pipe (diameter = d): Sh = 1.86(Sc. Re)0.8 for Re < 5 x 105 Stokes flow (Re < 1) to solid sphere: Sh = 1 + (Sc.Re)1/3 Forced convection around a solid Sphere: Sh = 2 + (Re)1/2 (Sc)1/3 Space for an example: 33 for 2 < Re < 200 A small droplet of fluid moving through another fluid with Stokes velocity: kM = (4DUb / d)1/2 (d = diameter of the particle; D = diffusivity of the species being transported; Ub = Stokes law terminal velocity) For a small particle moving through a fluid, the terminal velocity arises due to force balance between buoyancy and viscous drag force: Ub = d2 g / 18 = density difference; = dynamic viscosity of the fluid through which the particle is moving Example: 34 C17 - HEAT & MASS TRANSFER Examples Class (RVK) 1. The campaign life of continuously operating furnaces is limited by the fastest eroding section, which frequently is due to attack on the refractory walls by molten slag. One solution is to freeze a layer of the slag on the walls which protects the wall from the molten slag. This can be accomplished by placing water-cooled copper plates behind the refractory brick. Calculate the heat flux required and the thickness of refractory with a 0.05 m thick slag layer for a slag at 1473 K having a natural convection heat transfer coefficient of 100 W m-2 K-1 with the wall of the furnace. The freezing point of slag is 1373 K. Assume that the heat transfer coefficient remains unaffected when the solid slag layer is formed. The copper cooling plate behind the brick is 0.02 m thick, the cooling water is at 323K and that the water heat transfer coefficient for forced convection is 104 W m-2 K-1. Assume rectangular geometry. Also given the following data: Material Thermal Conductivity(k) W m-1 K-1 Water Copper Refractory Brick Slag (solid or liquid) 0.55 320 2 4 2. A steel slab 0.2 m thick x 1.0 m wide x 3.0 m long has been just withdrawn from a re-heating furnace (see attached diagram). Assume that temperature in the slab is uniform at 1273K. It is now moving along a roller system at a speed of 0.5 m/s, as illustrated. Assuming an ambient air temperature of 298K and ignoring radiation and natural convection effects, calculate: (a) the average convective heat transfer coefficient from the top surface; (b) the local heat transfer coefficient in the middle of the top surface; (c) the initial rate of heat loss from the top surface; (d) the temperature at the mid-point of the surface and at the middle of the ingot after one hour of cooling. State all the assumptions you need to make to solve this part. Data for steel: k = 38 W m-1 K-1; = 7200 Kg m-3; Cp = 400 J Kg-1 K-1; Data for air at film temperature of 785.5K: = 0.465 Kg m-3; Cp = 1088 J Kg-1 K-1; k = 0.0568 W m-1 K-1; = 7.9 x 10-5 m2 s-1; Prandtl number (Pr) = 0.688. 3. Show, using Fourier’s laws of heat conduction, that the Nusselt number has a limiting value of 2 for steady state heat transfer from a spherical particle to a motionless fluid (Also valid for very low values of Reynold’s number). 35 4. For corrosive and/or high temperature environments, metallic parts are often coated with refractory materials by plasma spraying. As shown in the schematic diagram, an arc is struck between the water-cooled anode and cathode, and nitrogen is injected down the annulus between the electrodes. The gas can be heated up to 30,000 K. The particles to be sprayed are injected into the jet through the anode, and they melt in their passage through the flame and solidify on the substrate. Calculate the maximum size of alumina particles that can be heated to its melting point (2300 K) in a 10,000 K plasma jet, assuming the particles enter the jet at the anode and remain in the jet until they hit the substrate. Ignore radiation from the non-polar gas employed. Given: the distance between the electrode and the substrate is 0.3 m; gas velocity is 6 m s-1 ; initial particle temperature is 298 K; k (nitrogen) = 0.08 W m-1 K-1; k (alumina) = 2 W m-1 K-1; Cp (alumina) = 1.25 J g-1 K-1; density (alumina) = 4000 Kg m-3. (Hint: Assume very small Reynold’s number) 36 37 C17 - HEAT & MASS TRANSFER Question Sheet (RVK) 1. A water-cooled copper lance, used for example to inject oxygen into a basic oxygen steelmaking furnace, has inner and outer diameters of 0.16 and 0.2 m respectively. Assume water flowing inside has a heat transfer coefficient of 15000 W m-2 K-1, and the furnace gases outside have an average coefficient of 400 W m-2 K-1. Determine the % of the total resistance that each phase contributes and the temperature at each interfaces given that the hot gas is at 2073K and the water at 273K. The copper lance usually has slag splashed onto it, which can adhere to the lance. What happens to the total resistance when 5 mm of slag freezes on the lance and how does this change the lance temperature profile? Given, thermal conductivity, k (W m-1 K-1): copper - 320; slag - 4. 2. Copper shot is made by dropping molten metal droplets at 1473K into water at 300K. Assuming the droplets to be spheres with diameter of 5 mm, calculate the total time for the droplets to cool to 373K, given the following data: For copper: Freezing point: 1356 K; Latent heat of fusion = 204 kJ Kg-1; Cp (liquid) = 502 J Kg-1 K-1; Cp (solid) = 376 J Kg-1 K-1; k(liquid) = 260 W m-1 K-1; k(solid) = 340 W m-1 K-1; (liquid) = 8480 Kg m-3; (solid) = 8970 Kg m-3; Quench data for water: h (1473 - 873K) = 80 W m-2 K-1; h(873 - 373K) = 400 W m-2 K-1; 3. Define “Biot Number” for a solid plate, stating the significance of this dimensionless number in heat transfer. How much Calorie (kcal) per day will an Emperor Penguin be generating in order to maintain its body temperature at 35oC, while standing stationary in the Antarctic weather condition with an average temperature of -25oC, given the following data: Average thermal conductivity of the Penguin, Heat transfer coefficient, 1 Calorie = 1 kcal = 4.2 kJ k: h: 1.0 W m-1 K-1 1 W m-2 K-1 You can model the Penguin as a cuboid of dimensions: 1 m height x 0.2 m width x 0.2 m depth. Calculate the surface temperature of the Penguin and the temperature profile within the body, under a stormy weather when the value of the heat transfer coefficient changes from 1 to 30 W m-2 K-1, assuming that the rate of heat generated is unaffected by the weather and that this rate is uniformly generated within the volume of the body. What is the maximum body temperature under these conditions? (Tripos 2010) 38 4. (a) Show that a cavity with a small aperture can be approximated to a black body for thermal radiation. (b) Describe how a practical black body radiation standard may be constructed. (c) Show that emissivity and absorptivity of any body at thermal equilibrium are equal. (d) The mass-transfer coefficient KM can be used to describe the rate of dissolution of an oxygen bubble rising in a liquid. Estimate the ratio of KM values for a given initial radius bubble in two cases: (i) for a bubble in molten glass at 1500K with a kinematic viscosity, ν = 104 Pa.s (ii) for a bubble in molten copper at 1500K with ν = 10-2 Pa.s (Tripos 2010) Answers: 1. gas: 94%; copper: 2.6% and water: 3.1%; T = 374K and 329K; gas: 64.5%; slag: 32.5; copper: 1.9% and water: 2.2%; T = 930, 350 and 313K. 2. 56 seconds 3. 1086 Cal/day; The maximum body temperature is at the centre, T (x=0) = -16.4oC 4. 10-3 39

![Applied Heat Transfer [Opens in New Window]](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/008526779_1-b12564ed87263f3384d65f395321d919-300x300.png)