I KNOW WHERE IS AN HYNDE - Associated Student Government

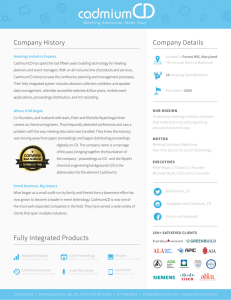

advertisement