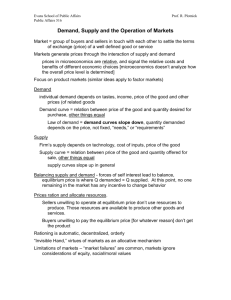

Econ 201 Lecture 6 Markets and Prices Why does Derek Jeter earn

Econ 201 Lecture 6

Markets and Prices

Why does Derek Jeter earn more than Sharon Weaver?

Why do diamonds cost more than water?

Why do Picasso’s paintings sell for more than Leroy Nieman’s?

Is it cost of production that determines prices (as Adam Smith thought), or is it willingness to pay that determines prices (as

Stanley Jevons thought)?

Alfred Marshall ( Principles of Economics , 1890) was the first to explain clearly how both costs and willingness to pay interact to determine market prices.

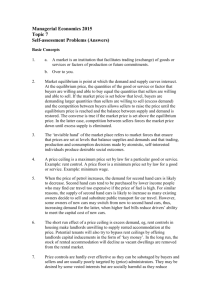

Supply and Demand Analysis: An Overview

Definition . The market for any good or service consists of all (actual or potential) buyers or sellers of that good or service.

The Demand Curve

Definition.

The demand curve for a good or service tells us the total quantity of that good or service that buyers wish to buy at each price.

The demand curve for lobsters:

Price ($/lobster) D

10

8

6

4

2

D

Quantity

0

1 2 3 4 5 (1000s of lobsters/day)

The demand curve is the set of all price-quantity pairs for which buyers are satisfied. ( "Satisfied" means being able to buy the amount they want to at any given price.)

Horizontal interpretation of the demand curve:

If buyers face a price of $4/lobster, they will wish to purchase 4000 lobsters a day.

Vertical interpretation of the demand curve:

If buyers are currently buying 4000 lobsters a day, the demand curve tells us that buyers would be willing to pay at most $4 for one additional lobster.

Demand curves slope downward for two reasons.

1. As the good becomes more expensive, people switch to substitutes.

2. As the good becomes more expensive, people can’t afford to buy as much of it.

The Supply Curve

Definition . The supply curve of a good or service tells us the total quantity of that good or service that sellers wish to sell at each price.

The supply curve for lobsters

Price ($/lobster)

10 S

8

6

4

2

S

Quantity

(1000s of lobsters/day)

0

1 2 3 4 5 6

The supply curve is the set of price-quantity pairs for which sellers are satisfied . ("Satisfied" means being able to sell the amount they want to at any given price.)

Horizontal interpretation of the supply curve:If sellers face a price of $4/lobster, they will wish to sell 2000 lobsters a day.

Vertical interpretation of the supply curve: If sellers are currently supplying 5,000 lobsters a day, the supply curve tells us that the marginal cost of producing the last lobster is $10.

2

One reason the supply curve slopes upward is the low-hanging-fruit principle. (Harvest the lobsters closest to shore first.) More generally, as we expand the production of any good, we turn first to those whose opportunity costs of producing that good are lowest, and only then to others with higher opportunity costs.

Market Equilibrium Quantity and Price

Equilibrium occurs at the price-quantity pair for which both buyers and sellers are satisfied.

Price ($/lobster)

D

S

10

8

6

4

2

S

D

Quantity

0

1 2 3 4 5 (1000s of lobsters/day)

At the market equilibrium price of $6 per lobster, buyers and sellers are each able to buy or sell as many lobsters as they wish to.

Excess Supply

A situation in which price exceeds its equilibrium value is called one of excess supply, or surplus.

At $8, there is an excess supply of 2000 lobsters in this market. excess

Price ($/lobster)

D supply

S

10

8

6

4

2

D

S

0

1 2 3 4 5

Quantity

(1000s of lobsters/day)

Excess Demand

A situation in which price lies below its equilibrium value is referred to as one of excess demand.

At a price of $4 in this lobster market, there is an excess demand of 2000 lobsters.

Price ($/lobster)

D

S

10

8

6 excess demand

4

2

S

D

0

1 2 3 4 5

Quantity

(1000s of lobsters/day)

At the market equilibrium price of $6, both excess demand and excess supply are exactly zero.

Example 6.1. At a price of $2 in this hypothetical lobster market, how much excess demand for lobsters will there be?

How much excess supply will there be at a price of $10?

3 excess supply

Price ($/lobster)

10

D

S

8

6

4 excess demand

2

S

D

0

1 2 3 4 5

Quantity

(1000s of lobsters/day)

The Trading Locus

When price differs from the equilibrium price, trading in the marketplace will be constrained-- by the behavior of buyers if the price lies above equilibrium, by the behavior of sellers if below.

Price ($/lobster)

D

S

10

Trading locus

8

6

4

2

D

S

Quantity

0

1 2 3 4 5 (1000s of lobsters/day)

Movement Toward the Equilibrium Price and Quantity

At prices above equilibrium, sellers are not selling as much as they want to. The impulse of a dissatisfied seller is to reduce his price. At prices below the equilibrium value, buyers cannot obtain the quantities they wish to purchase. Some buyers adjust by offering slightly higher prices. Thus, when price lies either above or below its equilibrium value, there is an automatic tendency for it to adjust toward equilibrium.

Price ($/lobster)

D

S

10

8

6

4

2

0

S

1 2 3 4 5

D

Quantity

(1000s of lobsters/day)

An extraordinary feature of this equilibrating process is that no one consciously plans or directs it. The actual steps that consumers and producers must take to move toward equilibrium are often indescribably complex. Suppliers looking to expand their operations, for example, must choose from a bewilderingly large menu of equipment options. Buyers, for their part, face literally millions of choices about how to spend their money. And yet the adjustment toward equilibrium results more or less automatically from the natural reactions of self-interested individuals facing either surpluses or shortages.

Example 6.2. Should Collegetown Rents Be Regulated?

Suppose the supply and demand curves for two-bedroom Collegetown rental apartments are as shown below:

Monthly Rent

($/apartment)

4

Supply

1000

Demand

0 2

The city council is concerned that many students cannot afford the equilibrium rent of $1000 per month and is considering a regulation forbidding landlords from charging more than $500. What will be the likely consequences of adopting this regulation?

Quantity

(thousands of apartments per month)

Monthly Rent

($/apartment)

Supply

1500

Excess demand=2000 apartments per month

1000

Controlled rent=500

Demand

0 1 2 3

Quantity

(thousands of apartments per month)

Rent Controls Produce Excess Demand in the Housing Market

Responses to excess demand in a regulated housing market: finder’s fees key deposits required furniture rental excessive damage deposits curtailed maintenance condominium conversion

There are much more effective ways to help poor people than to give them apartments and other goods at artificially low prices.

For example, income transfers:

Public service jobs

Cash on the Table

When a regulation prevents the price of an apartment, or any other good, from reaching its equilibrium level, the total economic surplus (economic benefits less opportunity costs) available for buyers and sellers is diminished. At a rent of

$500 in the rent-control example, there were tenants willing to pay as much as $1500 for an apartment. Similarly, there were for whom the opportunity cost of supplying an additional apartment was only $500. The difference— $1000 per apartment— is the additional economic surplus that would accrue to any seller who could rent an additional apartment for the price that tenants would be willing to pay.

Mutually beneficial exchanges are always possible when a market is out of equilibrium. When people have failed to take advantage of all mutually beneficial exchanges, economists say that there is "cash on the table"— our metaphor for unexploited opportunities.

The socially optimal quantity of any good is the quantity that maximizes total the economic surplus that results from producing and consuming the good.

Cost-benefit principle => keep expanding production of the good as long as its marginal benefit is at least as great as its marginal cost.

Socially optimal quantity is that level for which the marginal cost and marginal benefit of the good are the same.

Does the market equilibrium quantity also maximize total economic surplus?

In market equilibrium, the cost to the seller of producing an additional unit of the good is the same as the benefit to the buyer of having an additional unit.

If all costs of producing the good are borne directly by sellers, and if all benefits from the good accrue directly to buyers, the equilibrium quantity also maximizes total economic surplus.

When Smart for One is Dumb for All

Production of some goods entails costs that fall on people other than those who sell the good:

Goods whose production generates toxic smoke

Goods whose production generates noise

5

In the market equilibrium for such goods, the benefit to buyers of the last good produced is, as before, equal to the cost incurred by sellers to produce that good.

But since producing that good also resulted in the costs of the associated pollution, we know that the full marginal cost of the last unit produced—the seller's private marginal cost plus the marginal pollution cost borne by others—must be higher than the benefit of the last unit produced.

So market equilibrium quantity > socially optimal quantity. Total economic surplus would be higher if output of the good were lower. Yet neither sellers nor buyers have any incentive to alter their behavior.

Increases in production of some goods benefit people other than those who buy them.

Honey and apples

More bees => more apples

More apple trees => more honey

Market equilibrium results in too little production of such goods.

The Equilibrium Principle :

A market in equilibrium leaves no unexploited opportunities for individuals, but may not exploit all gains achievable through collective action.