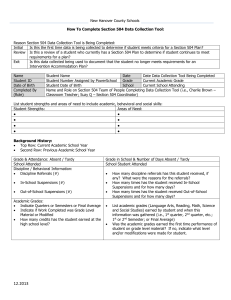

Student Services for Online Learning: Finding the Student's

advertisement