Diction and Syntax Review

advertisement

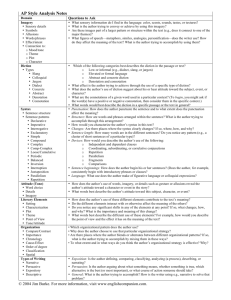

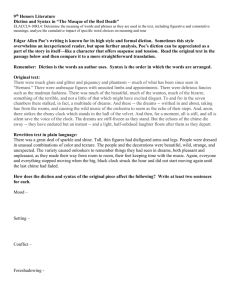

Diction and Syntax Review A. P. Lit. & Comp. Diction-In all forms of literature--nonfiction, fiction, poetry, and drama—authors choose particular words to convey effect and meaning to the reader. Writers employ diction, or word choice, to communicate ideas and impressions, to evoke emotions, and to convey their views of truth to the reader. Levels of Diction: • Formal (or high) Diction—usually contains language that creates an elevated tone; free of slang, idioms, colloquialisms, and contractions; often contains polysyllabic words, sophisticated syntax, and elegant word choice • Neutral Diction—standard language and vocabulary with elaborate words; may include contractions • Informal (or low) Diction—the language of everyday use; relaxed and conversational; often includes common and simple words, idioms, slang, jargon, and contractions Types of Diction: • slang—refers to a group of recently coined words often used in informal situations; often come and go quickly, passing in and out of usage o ex. As if! • colloquial expressions—nonstandard, often regional, ways of using language appropriate to informal or conversational speech and writing o ex. y’all • jargon—words and expression characteristic of a particular trade, profession, or pursuit o ex. The atoms of the macromolecular structure dissipated. • dialect—nonstandard subgroup of a language with its own vocabulary and grammatical features o ex. It’s fixin’ ta be five a’clock and I know y’all wanna’ go home. • concrete diction—specific words that describe physical qualities or conditions o ex. The tears came fast, and she held her face in her hands. When something soft and furry moved around her ankles, she jumped, and saw it was the cat. • abstract diction—language that denotes ideas, emotions, conditions, or concepts that are intangible o ex. impenetrable, incredible, inconceivable, unfathomable, etc… • denotation—the exact, literal definition of a word o ex. a house is a structural place where people may live • connotation—implicit meaning of a word o ex. “Home” has the connotation of safety, coziness, and security. Analysis of Diction: Use LEAD to analyze how an author’s word choices convey effect and meaning in a literary work. Low or informal diction (dialect, slang, jargon) Elevated language or formal diction Abstract and concrete diction Denotation and connotation Source: The AP Vertical Teams Guide for English. New York: The College Board, 2002. Syntax-The manner in which a speaker or author constructs a sentence affects what the audience understands. The inverted order of an interrogative sentence cues the reader or listener to a question and creates a tension between speaker and listener. Similarly, short sentences are often emphatic, passionate, or flippant; whereas longer sentences suggest the writer’s more deliberate, thoughtful response; and very long, discursive sentences gave a narrative a rambling, meditative tone. Types of Sentences: • Declarative—makes a statement: The king is sick. • Imperative—gives a command: Cure the king! • Interrogative—ask a question: Is the king sick? • Exclamatory—provides emphasis or expresses strong emotion: The king is dead! Long live the king! • Simple—contains one independent clause: The singer bowed to her adoring audience. • Compound—contains two independent clauses joined by a coordinating conjunction or by a semicolon: The singer bowed to the audience, but she sang no encores. • Complex—contains an independent clause and one or more subordinate clauses: Because the singer was tired, she went straight to bed after the concert. • Compound-complex—contains two or more independent clauses and one or more subordinate clauses: The singer bowed while the audience applauded, but she sang no encores. • Loose or cumulative—makes complete sense if brought to a close before the actual ending: We reached Edmonton that morning after a turbulent flight and some exciting experiences, tired but exhilarated, full of stories to tell our friends and neighbors. (The sentence could end before the modifying phrases without losing its coherence.) • Periodic—makes sense fully only when the end of the sentence is reached: That morning, after a turbulent flight and some exciting experiences, we reached Edmonton. • Balanced—phrases or clauses balance each other by likeness in structure, meaning, or length: He maketh me to lie down in green pasture; he leadeth me beside the still waters. • Natural order—subject before predicate: Oranges grow in California. • Inverted order—predicate before subject: In California grow the oranges. • Juxtaposition—a poetic and rhetorical device in which normally unassociated ideas, words, or phrases are placed next to each other, often creating an effect of surprise and wit: the apparition of these faces in the crowd/Petals on a wet, black bough. (Ezra Pound) • Parallel structure—grammatical or structural similarities between sentences or parts of a sentence: He loved swimming, running, and playing tennis. • Repetition—words, sounds, ideas are used more than once to enhance rhythm and to create emphasis: “The Government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.” (Abraham Lincoln) • Rhetorical question— question that requires no answer: Are you at your best today? • Rhetorical fragment—sentence fragment used deliberately for a persuasive purpose or to create a desired effect: Something to consider. Coordinating Conjunctions: FANBOYS (for, and, nor, but, or, yes, so) Advanced Syntax Techniques: • anaphora—the repetition of the same word or groups of words at the beginning of successive clauses: “We shall fight on the beaches, we shall fight on the landing-grounds, we shall fight in the fields and in the streets, we shall fight in the hills.” (Winston Churchill) • chiasmus—the arrangement of ideas in the second clause is a reversal of the first: “Ask not what your country can do for you; ask what you can do for your country.” (John F. Kennedy)