AN ANALYSIS AND PRODUCTION OF HAROLD PINTER'S OLD

advertisement

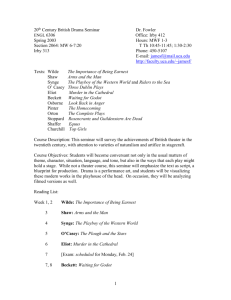

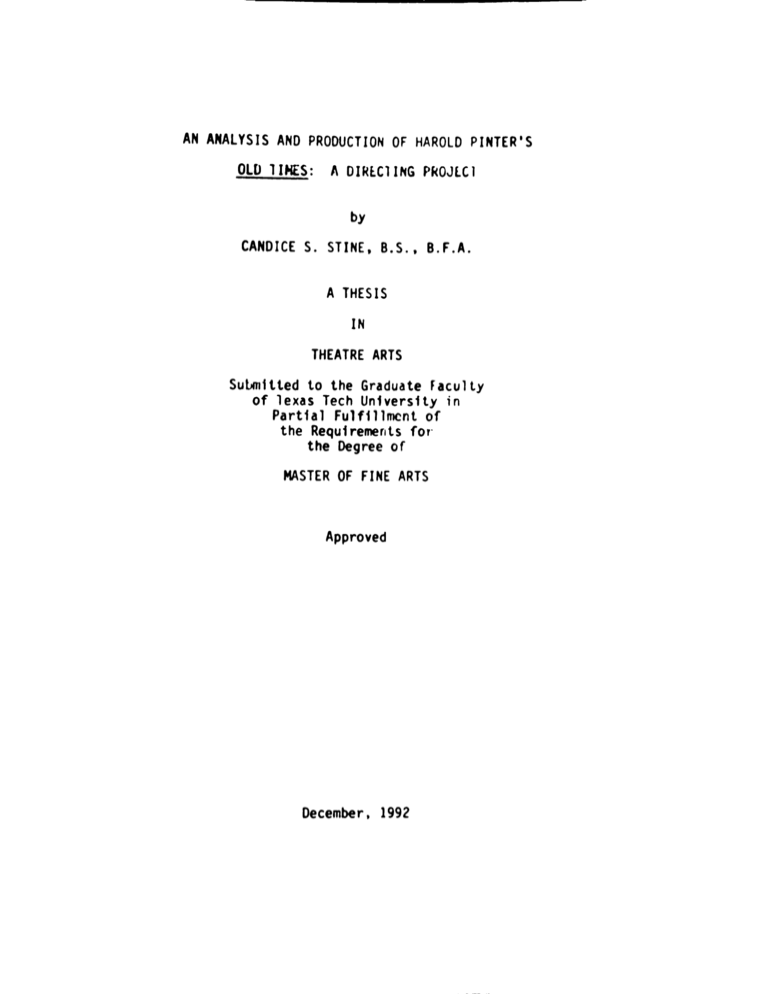

AN ANALYSIS AND PRODUCTION OF HAROLD PINTER'S OLD llfgS: A DIRLCIING PkOJLCl by CANDICE S. STINE. B.S.. B.F.A. A THESIS IN THEATRE ARTS Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Texas Tech University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF FINE ARTS Approved December, 1992 d^: P'^ ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS For all their assistance, encouragement, and suppoit, I am pirticulariy grateful to Dr. George Sorensen, committee chair, and Mr. Fred Christoffel. A very spedil thank you to my wonderful husband, Patrick Vaughn, for all your loving encouragement and support TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ii CHAPTER I. 1 II. INTRODUCTION CRmCAL BACKGROUND 3 m. CASTWG. DIRECTORIAL ALTERATIONS. AND BLOCKING.... H Casting 11 Directorial Alterations 14 Blocking ^ IV. PRELIMINARY INTERPRETATION OF THE SYMBOLISM. V. 15 ^1 TEXTUAL RESEARCa 32 CONCLUSION 39 SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY 41 VI. m CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION The plays of Harold Pinter are fascinating. His style of writing requires a different approach in acting and directing them. The actor must take the chance to explore the vast silences that Pinter requires and to make these pauses "live." The job that faces the director is to find the play that is happening beneath the surface of the words and to make it "Itve.** In June, 1990,1 directed Old Times by Harold Pinter at Texas Tech University. Since Pinter writes in a symbolic manner which requires his own style of acting, muchresearchwas needed. I decided to take a look at the man himself as a starting point for understanding his play. His boyhood, growing up in the midst of World War n, revealed a basis for his undertones of morbidity and why there is an unstated fear of the unknown in many of his plays. I began to realize the reasons for many of the elements that he puts in his woiks, such as the unbalanced uneasiness diat lies just beneath the surface. Realizing that Pinter's style might be intimidating to a young actor, I chose a mature cast and asked them to interpret the play in their own terms. This method was a part of the layering process that is needed to make this play multidimensional. There were some minor directorial alterations that enhanced the inteipretation and made the production more visually exciting. It is important to note, however, that the text of the play was never altered. 1 2 The blocking of this play is fairiy simple. The characters only move when they have areasonto and movement is kept to a minimum. Qld lim£& is based upon language, and die text is strong enough so that it does notrequiremuch movement Pinter's plays must be read many times over in order to realize the extent of the symbolism that he uses. Afterreadingit a few times, I felt that I understood his symbols, but still was not sure if they had been interpreted correctly. To examine other opinions, books by Martin Esslin, Elin Diamond, and others were consulted. Suchresearchshed a new light and enriched the production. _ CHAPTER II CRITICAL BACKGROUND Harold Pinter isregardedas one of the world's leading playwrights. He is as well-known for his unique style of writing as he is for his plays. Noel Coward once wrote of Pinter "Pinter is a very curious, strange element, he uses language marvelously well. He is what I would call a genuine original. Some of his plays are a little obscure, a little difficuh, but he is a supeib craftsman, creating atmosphere with words that are sometimes violently unexpected."^ Perhaps the violent and terrifying times in which Pinter grew up influenced his writing. Pinter was bom 10 October 1930, in Hackney, East London, to Jack and Frances Pinter. His family was poor, with his father making his living as a ladies' tailor. They lived in the east end of London until Pinter was nine. "l lived in a brick house on Thistlewaite Road, near Clapton Pond, which had a few ducks on it. It was a woiking class arearun down Victorian houses, and a soap factory with a terrible smell, and a lot of railway yards."^ In 1939, at the start of the war in England, Pinter was taken from the city to the country. He was sent to a castle in Cornwall that overlooked the English Channel. He did not like being so far from 1 Muftin FjBdin Pinter a Study of Hia Ptova. 3d ed.. ( Loodoo: Methuen and Comniv. 1970. The Pfcnpte Wound! the Plavs of Harold Pinter Loodoo: Eyre Methuen. 1977). 24. 2 Ibid.. U. .^ 4 home, and, after a year, he returned. His parents still did not feel that it would be safe for the boy, so they sent him away to school again, but this time closer to London. Pinterreturnedhome in 1944 to fmd London in shambles from the bombings. "There were times when I would open our back door and find our garden in flames. Our house never burned."^ During this time he began to attend Hackney Downs Granunar School, a boys' school that was only a ten minute walk from the Pinter family home. It was here that the young Pinter began his love affair with the theater. His English master, Joseph Brearley, is the person diat Pinter credits with introducing him to drama. Brearley directed the sixteen-yearold boy in Macbfilh and also as Romeo.4 After leaving the school in 1947, he applied for a grant to study acting at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art and was accepted.^ He stayed for only a short period of time, however, finding that he did not have the sophistication to cope with the other students. To escape, he faked a nervous breakdown and, unknown to his parents, tramped the streets for months while continuing to draw a grant.^ Pinter's version of why he left is much more concise: "I went to R A D A for about two terms, then I left of my own free will, I didn't care for it very much. I spent the next year roaming about a bit."^ 3 Ibid.,12, ^ Ibid.. 13. 5 Ibid. < Esslin. 13. "^ Harold Pinter, interview by Maitin Esslin. in Pinter a Study of His PUvi. 3d ed. (London: Eyit and Methuea. 1977). 13. 5 In 1949, at the age of eighteen, Pinter was eligible for National Service, but herefused,stating that he was a conscientious objector. Pinter appeared before two conscientious objector tribunals. He was not only denied the title on both occasions, but he was also fined for not appearing after he received his call-up papers.* In that same year Pinter began to write. At first he mainly wrote short stories and poems.9 It was not until 1950 that he had two of his poems, "New Year in the Midlands" and "Chandeliers and Shadows," published in Poetrv London . At first herefusedto write under the name "Pinter**; instead his works are published under the Portuguese form of his name "Pinta."»o In September of 1950, hereceivedhis first professional acting job, appearing in a BBC Home Service Broadcast entitled Focus on Football. In October he appeared in Focus on Libraries, ii On 14 January 1951, Harold Pinter made his Shakespearean debut on the BBC Third Program recording of Henry VII. playing Abergavenny. During this time he attended Central School of Speech and Drama. From September, 1951, to the fall of 1952, Pinter toured Ireland, playing Shakespeare.^^ In 1953 he * Esslin. 14. 9 AmnM P Hinrhliffe H«nM Pinter, 1>y«vBc«'i Enriiah Aidhon Series, cd. Kinlev Rolwr. no. 51 (Boston: O.K. HaU and COmptny. 1981). IS. 10 Esslin. 14. 11 Ibid. 12 HinchUfTe. IS. 6 joined Donald Wolfit's company. While he was with this company, he met the actress Vivien Merchant, whom he married in 1956.1^ Pinter's first play. The Room, was produced in 1957 by the Drama Department of Bristol University. The production was so successful that the Bristol Old Vic company also produced it and entered it in The Sundav Times' student drama competition. Pinter captured the attention of Michael Codron after an article about the production, written by Harold Hobson, a critic with The Sundav Times, appeared in the newspaper, i^ About this time Pinter wrote The Party (later titled The Birthday £ailX )• Codron was impressed with Pinter and asked him if he had any more plays. Pinter submitted The Birthdav Party and The Dumb Waiter for his approval. Codron expressed his interest in The Birthday Party, and he bought an option on it in January,1958. It was first produced three months later at The Arts Theater in Cambridge. In May of that year. The Birthday Partv was produced for the second time, this time for London audiences. The play was panned by the reviewers:i^ What all this means, only Mr. Pinter knows, for as his characters speak in non-sequiters, half gibberish, and lunatic ravings, they are unable to explain their actions,thought8 or feelings.16 13 Ibid. 14 Esslin. 16. 1^ Ibid. 17. 1< Esslin. 18. Sitting through The BirthHay Party at the Lyric, Hammersmith, is like trying to solve a crosswond puzzle where every vertical clue is designed to put you off the horizontal.17 The Birthdav Party ran only one week. Harold Hobson came to Pinter's defense in the 25 May Sundav Times! I have as a judge of plays by saying that The Birthdav Party is not a fourth, not even a second, but a first, and that Mr. Pinter, on the evidence of his work, possesses the most original, disturbing, and arresting talent in theatrical London.i> In Febmary, 1959, The Dumb Waiter had its first performance in Germany at Frankfiirt-am-Main. The Birthday Party was performed once again, this time at Canonbury, Islington, at the Tower Theater. The cast offered an inspiring performance, and the play was somewhatredeemedin the eyes of the critics. 1' A Slight Ache was broadcast by the BBC Third Prognunme on 29 July, and Pinter completed A Night Out in October that same year.^o In 1960, A Night Out was broadcast in March by the BBC Third Prognunme. It was then picked up by ABC-TV and televised in the United l^Ibid. 1* Esslin. 19. 19 Esslin. 21. 20 Esslin. 21. gUji^ 8 States in April.21 That same month The Caretaker opened at the Arts Theater in London. One critic wrote about the play: A fme play, consistently carried through apart from a few puzzling but not important details . . . a particular virtue is that nowhere does Mr. Pinter treat non-communication as an extraneous,ratherbanal 'point' to be made (compare lonesco's The ChairsV It is knit with the people and the action. Yet on must still say that this plunging of audiences into the world of the shut-off mind is someth^g that leads away from the main stream of art-whose main business, surely, is with the adultrelationshipswe painfidly try to keep and deepen. It is a fascinating byway and Mr. Pinter^s woik literally fascinates; but one hopes he will move on.22 The Homecoming opened at the Aldwych Theater in London on 3 June 1965. Harold Hobson, Pinter's old ally, wrote in The Sundav Times: Harold Pinter's cleverest play. It is so clever, in fact so misleadingly clever, that at a superficial glance it seems to be not clever enough. This is an appearance only, but it is one for which Mr. Pinter will suffer in the estimation of audiences, who will perceive an aesthetic defect diat does not exists. In the place of a mortal vacuum that does . . . I am troubled by the complete absence from the play of any moral comment whatsoever. To make such a comment does not necessitate, however, his having made up his mind about life, his having come to some decision.^ 21 Esslin. 22. 22 Ibid. 23 Esslin. 28. 9 On 3 January 1967. The Homecnming opened in New Yoric at The Music Box Theater. Its notices were less than enthusiastic: Mr. Pinter is one of the most naturally gifted dramatists to have come out of England since the war. I think he is making the mistake, just now, of supposing that the elusive kernel of impulse that will so for a forty-minute play will serve just as handily, and just as suspensefully, for an all-day outing . . . . We could easily take an additional act if the author would only scrap the interminable first.24 Old Times opened on 1 June 1971 at the Aldwych Theater in London. The reviews were mixed: A short piece needlessly passed off as a fiiU-length production with the aid of a late start and a long interval... as marvelous a theatrical poem as one hoped he would write after "Landscape."2s Continues to condense and attenuate his thought, and in the result to eliminate drama from his drama.26 For aU its brilliance. Old Times does seem about as minimal and rarefied as a play can be before sterility or self-parody sets in.27 2^Esslin.29. 25 Irving WanUe, The Times. in "Past. Present, and Pinter." Newsweek, 14 June 1971. p. 70. 26 John BartMsr. The Daily Telgyrayh, in "Past. Present and Pinier". Newsweek, 14 Jtne 1971. p. 70. 27 Christopher Poiterfield, "Memories as Weapons". Tune. 14 June 1971. p. 76L 10 In April, 1973, Pinter's one-man, one-act play. Monologue, was televised on BBC-TV. In the fall of that same year, he received an appointment as one of Peter Hall's associate directors at the National Theater. Two years later, Peter Hall directed No Man's Land at the National Theater at the Old Vic, and Monologue was produced by BBC Radio 3.2« Pinter has written numerous plays as well as screenplays not discussed here. The critics have been hard on him throughout his career, but he has survived and continues as one of the world's best known playwrights. Pinter has introduced a completely new style of playwriting. He is a bit absurdist and a bit expressionistic. In his unique style he has introduced another level to which the actor must rise to meet the needs of the script He has entertained, terrified, caused laughter, but, most of all, Harold Pinter has prompted thought 28 Hinchlifle. 20. CHAPTER III CASTING, DIRECTORIAL ALTERATIONS, AND BLOCKING Casting For the term project in the class entitled "Seminar in Directing Methods," I directed the final scene from Old Times. I cast young actors, hoping that the players might be flexible in learning the new style of acting that was presented to them. The problems encountered were that the cast had trouble interpreting the script and that I, as the director, had a hard time communicating the style demands to them. The young actors seemed intimidated by the script and appeared not to understand the style. All resisted playing the silences, perhaps because they did not understand that the pauses had to be played or perhaps playing them was frightening for them. This experience made me realize that, if I wanted to produce this play again, mature actors were needed to fill the roles. In June, 1990, Old Times was produced as a two-act play at Texas Tech University for the Alternative Theater Program. One of the first directorial decisions made was to cast mature, experienced actors. Before the firstrehearsaltook place, the cast received their scripts and were asked to read them. They were to come to rehearsal with their interpretations of the play. The first rehearsal consisted of a simple read through; however, the actors were instructed to communicate their individual interpretations as they read. I thought it imperative to find out the level of the actors' understanding of the play. 11 ii. A. 12 Each actor had his own ideas about the action and plot We did not discuss interpretation and the next step was for them tore-readthe play and to come torehearsalthe next day with a different perspective on it At the nextrehearsalperiod theyreadthe script once again. This time the actors were permitted to get up on stage and move. I was interested in Ending out how theyrelatedto one another and how they communicated their new interpretation to the other actors. All die while, the cast was not permitted to verbally exchange ideas on the meaning of the play. I wanted to give them some time to come to dieir own conclusions, without the other actors' interpretations coloring their own. It was not until the third session that the cast was permitted to exchange views. One of the actresses believed that Kate and Anna had been lovers; the other thought that they were the same woman; and the actor playing Deeley was of the opinion that the whole play was a dream. The cast requested that I give them my version of the meaning of Old Times. I declined to do so (not only at this stage, but during the course of the process) because I felt that all of their interpretations were valid. Qld Times could be about many things. There are so many different themes that Pinter deals with in this script that one person's views may color another^s. In order to prevent this influence from happening, I wanted to bring about a collaboration between the actors and the director so that the audience could think about their own interpretation(s) of the play. After hearing aU of these different interpretations, I realized that the correct decision had been made in casting mature actors. They seemed not to be intimidated by the difficult script Still, I had no idea how the cast would handle the new style of acting that was going to be presented to them. 13 During the first fewrehearsals,the pauses written into the script were stressed. The actors consistently either skinuned by them or did not take the pause at all. Like the younger actors, the cast members inteUectually grasped the concept of the "Pinter pause" after it was pointed out and explained, but they had a hard time in its execution. The immense pauses found in Harold Pinter's work is at the heart of his unique style. In trying to slow them down, I told them to allow two beats for the pauses. Communication of the style to the cast did not happen. They continued to speed through the pauses. The next step was to have the actors hold twelve beats, hoping that they might begin to feel the tempos and rhythms. The only outcome that this idea produced were actors who were counting beats. After it became apparent what was happening, the counting of the beats was abandoned. Instead, when the actors came to a pause, they were to hold the silence and stare at each other. Soon on-stage tension was established, and the cast members were side-coached to make them use what they were thinking or feeling during those moments. This technique appeared to work best in trying to get at the pause. Now it was time to make the cast realize that the silences needed to be acted. The players realized that Pinter only wrote part of what was happening into the script and that he left the other part up to the actor (and director) to convey in the pauses. At this point the actors seemed to feel comfortable enough with the script to "let go" and not to try to act; but they placed enough energy and tension in the pauses to make them have a life of their own. Only after diis scoring element was established did the tempo and rhythm problems iron themselves out 14 Directorial Alterations At the beginning of Old Times. Pinter has the character of Anna staring out of the window with her back to the audience. It is my belief that he did so in order that her presence would begin to raise questions in the minds of the playgoers. I have seen productions where the director conformed to this, and it indeed does lead the watcher to wonder what she is doing there, or if she is there at all. In this production, I chose to bring the lights up with Anna looking from the outside in, but not directly watching the action (or is she?). Her gaze seems to be directly above the heads of Kate and Deeley as they play the scene. Anna is watching something, and each person must decide for himself what it is. By letting the audience see Anna's face, I hoped to raise even more questions: Is she reaUy there? Is she watching Kate and Deeley? Is she looking at something else? At this point, I also wanted to symbolize the fact that Aima is in some way—but not really-a player in the game. She does not have that role until she makes her entrance at the beginning of the act When Anna became a player, the actress stepped from behind the window and made her way into the action of the play. This movement made a clear definition to the audience as to when she became a participant. By virtue of the script and interpretation, die watchers still were to wonder if she was really there or not. After having amended die first of die play, I felt die need to tie the end to the beginning. During the course of the play, the control that the characters exert over one another changes throughout the two acts. In the end it is Kate who finally gains control over herself, as well as die other two characters. It is diis final shift diat was emphasized in die end. I did 15 not attempt to change in any way what Pinter had written; instead, an epilogue was added. The fmal scene, when Deeley goes first to Anna, then to Kate, and fmally ends up back in his own chair (thereenactmentof Kate's rejection of Deeley), placed the three characters in their respective chairs, with Kate in the middle, Deeley on her left, and Anna to her right. The lights went down for five beats; then a spotlight flashed briefly on Deeley and then on Anna. Then the spotlight came up on the window frame with Kate, who is now watching something moving slowly toward the window frame and stopping in the same place that Anna was standing at the start of the play. Then the spotlight goes out, the actors exit, and soft hghts come up on the empty stage. This effect was used as a kind of a curtain call, as well as making a statement pertaining to therelationshipsand how they changed in the course of the performance. Kate was the one left in control, both of herself and the others. By being so, she was not in the game any longer, or j)erhaps she was in charge of the game. I felt that this ending left the viewer with more questions than answers because it does not tie up the story. Further, while the fmal scene brings the three characters full circle from the time when their association began, it also brings the viewers full circle from the start of the play, when their association with Kate, Deeley and Anna started. One of the objectives was to provoke the viewer into thinking about what he had just seen. Blocking The blocking for this production centered around a while nig at which all the characters' chairs were placed but on which none of the characters ever dared to walk. The idea was that all of the characters attempt to do so 16 during the course of the play, but only one will. The person that does so ultimately wins control. At the start of the play, Deeley and Kate are having a conversation about Anna. Both are seated, with Kate taking the center chair and with Deeley on her left. When Deeley asks, "What do you think she'd be like?"29 he gets up and walks down left. This move illustrates his feelings of dominance over his wife. When he feels that he has gained the control that he needed, hereturnsto his place. Aima's entrance overshadows the other two. She enters the action on her first speech. After achieving her goal, she takes the seat to therightof Kate. This action signals her comfort at having won the first battle for control over Kate. The next section of blocking comes immediately after Anna sits. Kate stands after Deeley's line, " We rarely get to London.''^^ She walks around the white rug and goes to the table down right, pouring coffee for all, first giving one to Anna and then to Deeley, and thenreturningto her chair, all the while never stepping on the rug. Deeley sees this action as some kind of challenge. He asks Anna, "Do you drink brandy?"^! He gets up and walks down left and pours a drink for the three of them. He hands the brandy to each of the ladies, walks back to the table, and stares out into the nothingness as Anna did at the beginning. Hereturnsto his chair after a pause which is broken by Anna's question, " Listen. What silence. Is it 29 Harold Pinicr, Old Times (Grove Press. New York. 1971), p. 14 50 Ibid. p. 18 31 Ibid. 17 always as silent?"32 At this point Deeley feels that he has regained control of the situation from the women. Anna is the next to move. She goes to the window and looks out on her line, "And the sky is so still." Sheremainsthere until her line, " I'm so delighted to be here."33 At that moment she once againreturnsto her chair. It is unclear whose battle it has been, for no one appears to be the winner. This control, however, changes a little later in the play when Deeley and Anna begin to reminisce about the songs that they heard in their youth. They start out innocently enough, each singing to Kate. Slowly the intensity builds to a climax, with both Anna and Deeley standing and walking to center stage. Kate is still visually between them. They lock eyes. In the silence both battle for control. Deeley ultimately wins by breaking the silence, and Anna backs down, retuming to her place while Deeley starts his monologue. He walks behind the three chairs and comes to a stop between the two women as he speaks of the two lesbian usherettes. Deeley retums to his seat the way he came so that he does not step on the rug. He feels that he has won this battle. The players remain seated during both Deeley's and Anna's monologues ("This man crying in our room,"^^) Kate begins to feel the need to break away from the other two. She stands on Deeley's line, "But was he--,"35 cutting him off once again as she makes her way to the down right table and pours herself a drink. Deeley, feeling 32 Ibid. p. 19 33 Ibid. p. 22. 34 Ibid. p. 32 35 Ibid. p. 34. IS her flight, follows her to the table on his line, " I couldn't have put it better myself."36 A challenging silence follows between Kate and Deeley. Kate wins by taking the cigarette box away from Deeley and handing it to Anna. It is evident that Deeley is losing the game. He admonishes the women for what he perceives as leering at each other. Kate sits in her chair. Deeley pours himself a drink and retums to his chair behind Anna and Kate while delivering his speech, "Myself I was a student then."37 The next place that blocking occurs is at the end of Act I, when Anna and Kate are in their own little world, leaving Deeley "odd man out." On Anna's line, "Don't let's go out tonight,"38 she crouches beside Kate's chair. She remains there for the duration of her monologue, standing and facing her empty chair on the line, "You'll only want to come home if you go out."39 Anna turns to Kate when she asks, "What shall we do then?"'*^ At the end of the act, Kate, knowing that she has won this round, because Anna and Deeley have been jockeying to control her and neither one has done it, proclaims that she will run her own bath. Kate walks around the back of Anna and off the stage through the audience. The act ends. For Act Two, most of the furniture stays in the same position, with the white rug in center stage. The only piece that changes is the table; it drifts 36 Ibid, P- 35. 37 Ibid. 38 Ibid, P- 43. 39 Ibid. P- 44. 40 Ibid. 19 to down left. Deeley enters from the house onto the stage and places the tray of coffee that he is carrying on the table. All the time he and Anna are conversing. He carries a mug of coffee over to Anna, who is sitting in the center chair. He sits in his chair after giving her a lesson on the beds on which they are sitting. What occurs next is a verbal sparring match between the two. The charactersremainseated during this time, but physical, as well as mental, tension increases. Kate makes her entrance during the silence that occurs after Deeley's line, " If I walked into The Wayfarers Tavern now, and saw you sitting in the comer, I wouldn't recognize you."^i She enters from the house, walks behind the chairs to where Anna is sitting and, non-verbally, makes Anna move over to her right. This action symbolizes the shift in pecking order, but Kate is always in the center. She is always stable. Anna once again begins to jockey for Kate's attention by walking to down left, pouring her a cup of coffee and bringing it to her. After doing so, Anna sits in the same chair until Kate complains that the coffee is cold, and Anna goes to her and then back to the table. After Kate says that she does not want another cup, Anna sits. As the play progresses, Deeley senses that he is losing ground in the game. In desperation Deeley rises from his seat when he begins his sF>eech, "Yes, but you're here, with us. He's there, alone, lurching up and down the terrace, waiting for a speedboat to spill out beautiful people, at least."-^^ Deeley makes a half circle around the back of the chairs and stops between 41 Ibid. .57. ^2 [bid. 67. 20 the two women on the line, "Why should I waste valuable space listening to two--."43 He then finishes the circle by saying, "You know what they'd do to me in China if they found me in a white dinner jacket."^^ The rest of the dialogue is performed by the characters seated in their chairs. The prose is so descriptive that the blocking got in the way of the play. When Deeley, Kate, and Annareenactthe "man in the room" sequence, the next blocking section takes place. Deeley starts to walk away offstage, finds that he cannot, walks down right, stands by Anna, then walks to Kate and kneels, gets up, crosses to and sits in his own chair. The play ends. For the most part, blocking was kept to a minimimi. The word play in the script is so strong that excessive movement would distract the viewer who is trying to listen to what is happening. Much of the blocking of the play resulted from my interpretation of Pinter's script. I chose to incorporate my interpretation of Old Times not only into the blocking but also into the method in which the pauses and silences were handled. 43 Ibid. 44 Ibid. CHAPTER IV PRELIMINARY INTERPRETATION OF THE SYMBOUSM From the very start of the play the question arises about what is occurring. Pinter sets this up very astutely by having Anna on stage and Kate and Deeley talking about her. It is not evident whether Anna is really there in the room or if the event is a dream (and if so, whose dream is it? Or perhaps it is a nightmare?). Is Anna dead and is Kateremembering,or is it real? (If so then whose reality is it?) Pinter chose not to define any of the questions, instead letting all interpretations be present so that the viewer would question the reality. By Kate's responses to Deeley's questions it is apparent that she will not be pleased to see Anna. That raises the question, "Why?" It is perhaps because of her evasiveness when her husband asks her about the time that she and Anna lived together. The question suggests that there was more involved than just friendship. Pinter hints at a lesbianrelationshipthroughout the play. One of the places that he touches on it is the section in which Anna tells Deeley, "You have a wonderful casserole . . . I mean wife. So sorry. A wonderful wife."45 Earlier, Deeley says that Anna might be a vegetarian but that it is too late because Kate has already cooked her casserole.46 The term, 45 Ibid. 46Qldjnni£S. 12 21 22 "vegetarian," therefore, takes on the sexual meaning of "straight" The casserole, thus, becomes the symbol of bisexuality. By Anna's reference to Kate as "a casserole," she may be offering a hint that they may have been lovers.47 This possibility is further substantiated when Kate begins to join in this dialogue: Kate Yes, I quite like those kind of things, doing it Anna What kind of things? Kate Oh, you know, that sort of thing. Deeley Do you mean cooking? Kate All that thing.^ Pinter suggests theu- pastrelationship,but he never makes a concrete statement about it From the very start of Old Times, therelationshipbetween Deeley and Kate is apparent. Kate seems autonomous in her being, and Deeley faces a constant struggle in trying to penetrate her shield of defensive independence. Pinter offers some insight into this autonomy through 47 cn^ti^th Q«lr#>n«rirfnM cMTifc to the Mine coaclunon in her hnnk Pint<V« Bwn«U Pr^trijiy A SIIM^ ^ BMMle rharactew in the Plav« nf Harold Pinter ^ Ibid, 21. 23 Deeley's investigation of her past when he finds out that Kate was a "loner" even in her youth. As Anna was the only friend that she had, the possibility emerges that Anna was the only person who could break through her defenses. From the game that ensues, it is apparent that she could not. Anna seems to be fighting for the same thing that Deeley is, that is, to break down her defenses and possess her. Anna's entrance once again raises the question of a dream or reality. The fact that her entrance from behind the window has a disjointed quality to it leads one to believe that it might be a dream. When she enters, she facilitates new action, and perhaps it is "reality." On her entrance, Anna begins to reminisce about the "old times" that she and Kate shared. She ends her monologue by asking if Kate is the same person that she knew in her youth. Kate, having become caught up in the other woman's memories, allows a glimmer of her younger self to emerge. By her reply, there is obviously still a bit of the young Kate left. The overall feeling of this script is that it is a game-a three-way tugof-war between the three characters of Kate, Anna, and Deeley. Both Anna and Deeley are vying not only for Kate's attention, but for her affections as well. This conflict is demonstrated throughout the play, but Pinter makes it very apparent in Act One when Deeley and Anna begin singing to Kate. At first the songs seem innocent enough; however, Pinter has chosen songs that carry a definite message to the listener. Deeley starts with, "You're lovely to look at, delightful to know . . . "^9 Deeley cares for Kate. The next lyric that he sings to her is. "Blue moon, 1 see 49 Ibid.. 27. 24 you standing alone . . . "^ In this line, he may bereferringto Kate's appearance of autonomy, which he has never been able to penetrate. Anna joins in with, 'The way you comb your hair.. .,"5> suggesting that she is familiar with Kate. Deeley finishes her phrase by telling Anna, "Oh no they can't take that away from me . . .,"^2 implying to her that he will fight for Kate. This section is the point that the struggle comes to a climax. During the course of their singmg, the tension between them escalates to a conclusion of "screaming silence"-a silent battle for power over the situation and, ultimately, over Kate. The winner in this struggle is questionable. Deeley breaks the tension. He begins his monologue about the first time he met his wife. His speech is visually very colorful as he recounts the events. As he reminisces, the symbolism in his words emerges: What happened to me was this. I popped into a fleapit to see Odd Man Out. Some bloody awfiiil summer afternoon, walking in no direction. Irememberthinking there was sometl^g familiar about the neighboihood and suddenly recalled that it was in this very neighborhood that my father bought me my first tricycle, the only tricycle in fact I had ever possessed. Anyway, there was the bicycle shop and there was -this fleapit showing Odd Man Out and there were two usherettes standing in the foyer and one of them was stroking her breasts and the other one was saying "dirty bitch" and the one stroking her breast was saying "nunnnn" with a very sensual relish and smiling at her fellow usherette, so I marched in on this excruciatingly hot summer afternoon in the middle 50 Ibid. 51 Ibid. 52 Ibid. 25 of nowhere and watched Odd Man Out and thought Robert Newton was fantastic. And I still think he was fantastic. And I would commit murder for him, even now. And there was only on other person in the whole of the whole cinema, and there she is. And there she was, very dim, very still, placed more or less I would say at the dead center of the auditorium. I was off center and haveremainedso. And I left when the film was over, noticing, even though James Mason was dead, that the first usherette appeared to be utterly exhausted, and I stood for a moment in the sun, thinking I suppose about something and then this giri came out and I think looked about her and I said wasn't Robert Newton fantastic, and she said something or other, Christ knows what, but looked at me, and I thought Jesus this is it, I've made a catch, this is a trueblue pickup, and when we had sat down the cafe with tea she looked into her cup and then up at me and told me she thought Robert Newton was remarkable. So it was Robert Newton who brought us together and it is only Robert Newton who can tear us apart.53 Pinter brings out the parallel between the fact that it was from this same neighborhood that his first tricycle came and that he met his wife. He uses the word "possessed" to describe the tricycle, leading one to believe that he wishes to do the same to Kate. In this speech, Pinter is very clever in using the film. Odd Man Out, as a description of Deeley's feelings. It is uncertain, however, if his feelings of insecurity range only in this threeway encoimter -- if this is how he perceives himself in life, or perhaps both. Once again, Pinter uses symbolism toreferto the possible lesbian relationship. This time it takes the form of the two usherettes in the foyer. After Deeley evidently watches them for awhile, he leaves to go into the theater to see Odd Man OuL which, once again, refers to how he feels about the relationship between the two women. 53 Ibid.. 30. 26 There is a puzzling aspect in this monologue-the reference to the handsome English actor, Robert Newton. Perhaps the author included it as a key to Deeley's personality. Maybe it questioned Deeley's sexual tendencies. The reference to Deeley's thinking that Robert Newton is fantastic and would kill for him and that only Robert Newton can come between him and Kate suggests an attraction on the part of Deeley. Pinter uses Deeley's meeting with Kate as exposition to set up what comes next. The remembrance of Kate and Deeley's first lovemaking, his thinking that she was even better than Robert Newton, and his wondering what Robert Newton would think of their lovemaking supports the theory that Deeley has bisexual, if not homosexual, tendencies. It is Anna's next line that is the most important in the play, for it states the theme: I never met Robert Newton but I do know what you mean. There are some things onerememberseven though they may never have happened. There are things I remember which may never have happened but as I recall them so they take place.54 The play deals with the way in which three different people all remember the same series of events. By the time each finishes recalling them, it is uncertain if they happened or not. For the characters, however, these events happened for them the way that each one remembers. Pinter points out that all can remember the past, but, because all perceive it differently, each person will remember it differently. Anna's line sets up her speech about the man crying in their room. She talks of the man who is sobbing, having been sexuallyrejectedby Kate. 54 Ibid. 31. 27 coming over and standing over Anna in her bed, and her rejecting him as well. From Deeley's reactions, one can assume that she is speaking about him. Later on in the play, he recounts his version of the rejection. Perhaps the fact that the two women had such a close association at one time leads Deeley to feel left out now. This might be his reasoning for giving such a cold account of Kate or saying: "Well, any time your husband finds himself in this direction my little wife will be only too glad to put the old pot on the old gas stove and dish him up something luscious if not voluptuous. No trouble." This speech can be seen as his chance to put Kate in her place, as he sees it, or it could be viewed as his invitation to sexually share Kate with Anna's husband. Either way it is his attempt to control or possess Kate. At the end of Act I, when Kate and Anna begin to converse and Deeley is left out of the conversation, a hint of desperation emerges on his part. He tries to control their conversation by talking about himself and his work. He boasts by saying that he is Orson Welles and that he is at the top of his profession. He fmds that he is being tuned out and intrudes into their conversation about Sicily: "There's nothing more to see, there's nothing more to investigate, nothing. There's nothing more in Sicily to investigate."^^ He begins torealizethat he has lost this round, for the women have become lost in each other. Anna's attempt at control is not quite as overt. She draws Kate into her memories and becomes overiy protective of her. This protectiveness is the method that she uses to exert control. While Anna and Kate are drifting 55 Ibid. 43. 28 into the past, Anna does Kate's bidding. At the end this small exchange occurs: Kate m think about it in the bath. Anna Shall I run your bath for you? Kate No. I'll run it myself tonight This passage suggests that Kateremainsthe ultimate winner in this round, for she remains autonomous by running her own bath. Also, it is Kate who maintains control over both Deeley and Anna because all of the action revolves around Kate, and she gets them both to heed her bidding. The manner in which Pinter writes the characters of Kate and Anna, each one being what appears to be the complete opposite of the other, leads one to think that the two women are really one. Deeley is, for the first time, realizing that his wife is more than he expected— that she has more than one side to her personality. Pinter's style of writing changes shghtly in Act n. His descriptions become more vividly alluring. His words become sensual The opening of the act finds Deeley and Anna in Kate's and Deeley's bedroom. Pinter uses this setting to develop an act that is filled with sexual symbolisoL Deeley starts off the scene by explaining to Anna about the beds and how they can be moved to many different positions. Perhaps Deeley uses this explanation to symbolize different sexual positions as a covert come-on to Anna. 29 Deeley recounts to her the time he saw her in The Wayfarer's Tavern. Deeley's recollections become veiy sensual. Using the "same woman" theory, it could be argued that Deeley is trying to draw out the sexually passionate side of his wife's personality. On the other hand, he might be trying to draw Anna into having an affair. He might also just be letting her know that he is aware of her past and of herreputationas a "loose woman." It is certain that Pinter is once again setting up for each person's perception of the past. Perhaps Deeley might have some fascination with the idea of Arma and Kate having been lovers. In the next section, he begins to talk of Kate and her baths. His description becomes very sensual and draws Anna into his imagery. It is obvious by the maimer that Anna talks of Kate's coming out of her bath that she still harbors an attraction to her. Deeley picks up on this possibility and suggests that Aima dry Kate while he watches. He also suggests that he will powder her while Aima watches. This section hints that he has a desire to watch while the two women make love, or to be watched while he makes love, but also that he might desire a menage-atrois with the three of them. Kate's entrance as the two other characters serenade her marks the fact that the game has started once again. Kate's fu^t speech is very descriptive in its sensuality. In it she tells of how she prefers living in the country to the city. This statement could be interpreted as her preference to living a straight life as opposed to when she and Arma were lovers. Still trying to win control, Anna begins to wait on Kate with a cross between motherly over-protectiveness and indentured servitude. At the end of Act I and again in Act II, the ladies discuss the men friends that they k 30 had in the city, suggesting that they were not lovers, but women who shared a very loose morality. Pinter uses the sexual references and games of control as a method to play on the past. The characters wonder about the distortion of memory that occurs with time. Kate's speech at the end of the act suggests more questions than answers. She makes it known that she loves Deeley and speaks of the time that she chose him and what he had to offer over her life with Aima. In the monologue she symbolically kills Anna, putting her out of her life. She then brings Deeley into her world. She expounds on the time that he tried to have sex with her and that sherefusedhim, smearing dirt on his face and dirtying him as she felt that she had been dutied. In order to have her, he asked her to marry him. Kate's final line causes questions about whatreallyhappened between the two women: "He asked me once, at about that time, who had slept in that bed before him. I told him no one. No one at all."s6 The next section contains action that Pinter includes. Anna stands, starts to walk to the door, stops, and then walks back to her place, while Deeley starts to sob. He stops crying, goes to Arma, stands over her looking, turns and starts for the door. He stops, tums, and walks to Kate, sits next to her and hes across her lap. He gets up and goes to his chair and sits.^^ Pinter uses this prolonged silence with action to tell his audience that the only winner that emerged from this confrontation is the person who 5«Ibid. 57 Ibid, 31 maintained control throughout the play-Kate. In the end she not only rejects Anna but also Deeley. Harold Pinter uses a unique blend of expressionism and absurdism in writing Old Times . By using the elements of expressionism he provided a dream quality that makes the viewer wonder if the play's action is reality or a dream. He uses the absurd quality of the story to make the viewer perceive that this not a dream but a nightmare. He leaves it open to question, however, as to whose dream or nightmare. By giving Old Times dream qualities one wonders if the action is reality or peihaps all that happens is part of someone's memory. Pinter emphasizes the non-conmiunication that occurs among people. Each of the characters lives in his own world, only perceiving what he wants so that his world can survive. There are many inteipretations that can be applied to this play. When asked what Old Times was about, Harold Pinter himself said, "It happens, it all happens." ^^ He tells so much-yet nothing-at the same tinne. Pinter does so in order to make the director, the actors, and ultimately the audience think. ^ Elinttfth g'^^ll^r^A^i Wnier'* Female Pbrtraka m a m a Mid NoMg Bonla^ Tninwa ¥imm W»>y lOM) P.14S. CHAPTER V TEXTUAL RESEARCH Rehearsal andresearchuncovered elements about the play that had not been previously considered. Among the elements were Absurdism (the non communication between characters), the use of mask (the manner in which the characters deal with each other on different levels at different moments), and the comic elements (how Pinter uses farce to illustrate the ludicrous qualities of the characters). During the course of theresearch,it was discovered that many different authors had many interpretations of Old Times, some agreeing with this director's interpretation and some not. All brought new and varied ideas to hght. Martin Esslin, author of books on Pinter and interpreter of his plays, sees Old Times as happening on three levels, with the first level considered as the reaUstic one. The play is a battle between a husband and his wife's old girlfriend for her attentions. Deeley and Anna use their memories as weapons in the battle. The next level that he suggests is that the play is a dream, or more specifically, Deeley's nightmare. Esslin raises the question: "Is Deeley merely anticipating in a dream, or in his worried imagination, what would happen if the long lost girlfriend, from the past suddenly re-emerged?" The third level is that Anna is really present at the 32 33 start of Act I, which makes the action of the play a kind of game. Perhaps this game is played by the threesome on a regular basis.59 Alan Hughes states that "Anna has no objective existence" and that "the Anna of today is fiction." From these assumptions Elizabeth Skelleradou proposes four interpretations: (1) that the whole play is Deeley's nightmare; (2) that Kate's and Anna's past intimate relationship stands as a psychological barrier between Kate and Deeley; (3) that Kate and Anna are different sides of the same woman, and Anna is the part that Kate rejected, or the part that Deeley wishes Kate were, or perhaps both; or (4) that Deeley and Kate are playing a ritualized game that is a part of their sexual foreplay. She offers further a fifth interpretation: that Deeley has been dead for at least a period of five years, and the events are happening in Kate-Anna's mind.^ No one person has been able to come up with one definitive interpretation of Old Times. As stated earlier Pinter says, Til tell you one thing about Old Times. It happens. It all happens."^i Skellaradou suggests that Pinter's comment is vague and ambiguous. It does not verify if the action is really happening or only taking place in the minds of the three characters. Thus, in making the statement, Pinter leaves the door op>en to all who interpret the play as an enactment of fantasy or memories." 59 Martin Esslin. 36. 60 Elizabeth Sakcliaradou. 48. 61 Ibid. 62 Ibid. 34 Some of the interpretations between the two authors are the same, and some are different. Esslin states that in Pinter's plays all interpretations do not cancel out each other, but they have to 'co-exsist to create the atmosphere of poetic ambivalence on which the image of the play rests."^^ In presenting the play to the cast, it was stressed that there was more than one inteipretation of the play and that all were to be taken into account and presented to the audience. The research substantiated my earher ideas that Kate and Anna are separate parts of the same woman and that the action is part of Deeley's nightmare. Furthermore, the entire play is aritualizedgame that the characters are playing. Reasoning behind the motivation for playing the game differs, however, in that the game is more of an effort to gain control of Kate than a sexual foreplay. Old Times contains traits of absurdism. The text and the action are circular. For example, Pinter has written the end of the play similar to the beginning. The circular pattem of text and action remove the play from perceived reality. Thisrituahzedpattem may go on for eternity. Also, Theater of the Absurd focuses on man's inability to communicate," a theme that Pinter touches on at the start of the play with Kate and Deeley. It becomes apparent by the way that Deeley is questioning Kate and the manner in which she answers him that they do not communicate well with each other 63 Martin Esslin, 67. 64 Carlson. Marvin and Yvonne Shafcr. The Plav's the Thing: .\n introduction to Theariy (Longman, New York, 1990). 613. 35 and, consequently, know very little about each other. Perhaps they do not want to know. One of the elements that Pinter places in Old Times that requires research was the use of the film, Odd Man Out. In Chapter II, it was referred to as Deeley's feeling left out when the two women are together. There had to be another reason that Pinter placed the title of the film in the play. One author agreed with the interpretation that "Deeley makes repeatedreferencesto his own varied inversion. He identifies himself with the movie title Odd Man Out, and he also speaks of himself as 'off center.'" Odd Man Out seems to indicate that his attraction to Kate left him outside of her homosexual attachment to Anna. His reference to "off center" and later comments about traveling east or in certain directions are appropriate to a conclusion about Freud's dream symbolism: Thus 'left' mayrepresenthomosexuality, incest, or perversion and 'right' may represent marriage, intercourse, with a prostitute, and so on, always looked on from the individual's standpoint.65 If Deeley is "off center" he can deviate in either direction. During the movie he was attracted to Robert Newton and vented his arousal on Kate.^^ Elin Diamond asserts that the movie enters the play at four levels: (1) it provides a meeting place for Deeley. Anna, and Kate (Did they see the 65 Lucinda Paquet Gabbard. The Oream Structun: of Pinters Plavs: A Psvchanalvtic Approach (Faulegh Dickinson University Press. lx)odon. 1970), 242 66 Ibid. 36 film together or apart?); (2) Odd Man Out illustrates the game-like behavior that two of the characters play, leading to the third one being "Odd Man Out"; (3) the movie uses flashback to further the plot, and Pinter utilizes this technique in the scenes that Kate and Anna have together; or (4) the plot of the film evokes the theme of perpetual distortion.67 The research indicates that the original ideas were not off the mark. All agree that Deeley was feeling left out, while Kate and Anna were playing the game that left him out of their clique. Also discovered are Deeley's homosexual tendencies. This fact emerges from his feelings about Robert Newton after seeing the film. The next matter concerning interpretation was Anna's statement in Act I: "There are some things Irememberwhich may never have happened but as I recall them so they take place."^* Pinter might be using this line to comment on the main theme of the play, the way in which p>eople remember the same incidents differendy. On the other hand, he might be conmienting on the non-commimication between people. Martin Esslin agrees with the latter.^^ Eiin Diamond, however, asserts that "in Old Times past and present are a matter of linguistic choice, mirroring the characters perceptions and desires."^o She goes on to say that Pinter uses 67 EUn Diamond, pjnt^'r'^ Comic Plav. (Associated University Press. 1985), 165. 68 Old Times. 69 Esslin. 70 Diamond. 37 this passage to comment on this technique.^i Perhaps an argument could be made that both views are one and the same. In the course of the rehearsal time, it became evident that Old Times is one of Pinter's comedies. Exposure, game playing, non-naturalistic verbal performance, and motive hunting—all associated with a Pinter comedycome out in Old Times."^^ Pinter achieves these techniques through his expert use of language. Diamond states: Pinter gives prominence to the power of language not only to describe but to create an experience. The Fact that (Deeley and Anna) discuss something that (Deeley) says took placeeven if it did not take place-actually seems to me to recreate the time and moments vividly in the present, so that it is actually taking place before your eyes-by the words he is using.''3 The use of the competition between Deeley and Anna with memory, songs, and stories allow them to try and take possession of Kate. Their competition for Kate's affections becomes comical and revealing. The word-play between the two begins to reveal frustration by the release of sexual hostility.*''* The director allowed the actors to find the places that the word-play occurs and play them-not by playing them for the laughs, an impossibility 71 Diamond. 72 Ibid. 73 Ibid. 74 Diamond. 38 in a Pinter play, but by lightening those overtones. The play as a whole cannot be played with a deep seriousness but must have a lightness to it so that the undertones of humor can break through. One of the most interesting facets of Pinter's work occured during the rehearsal process—his use of the mask. Each of the characters has a mask that he wears with the others. For example, Deeley has a mask that he wears when he is alone with Kate, but another when he is with Kate and Anna, and still another when he is only with Anna. Deeley does not consistently wear his mask, and each mask that he wears is different. He puts it on and takes it off for different reasons. The actor must choose those moments when he is wearing a mask and when he is not. When the character is wearing his mask, he appears at his most vulnerable level. The mask does not hide, as some would think, but lets the actor reveal his true feelings. Old Times is a complicated play that has many layers to it. It has been dissected many times and each time a new layer has been discovered. Pinter has written this play so that it fascinates and perplexes those who attempt it. CHAPTER VI CONCLUSION The life of Harold Pinter reveals a solemn man whose childhood was filled with the terror of war. It is easy to see this refection in his plays. There is a certain uneasiness or inbalance that prevails in his work this is meant to keep the audience unsure and guessing as to what will happ)en. In an earlier project, I began to realize that the works of Harold Pinter can be intimidating to the inexperienced actor, and a cast of mature players was chosen for this production of Old Times. By doing so, the actors could bring their interpretations through their experiences and the layering process could begin. Minor alterations to the beginning and the end served to enhance the interpretation of the play. The changes did not occur in the text of the play; they were the manner in which the curtain call was handled and Anna's entrance at the beginning. Blocking was kept at a minimum due to the fact that I felt that that was what the script demanded and that the language was strong enough to stand on its own. Old Times contains a lot of strong symbolism which had to be interpreted and researched. Authors such as Martin Esslin, Arnold Hinchliffe and others shed new light on the various interpretations of Pinter's play. Pinter's Old Times brings together his humor, torment, and his perceptions on the ambiguity of life. In the production at Texas Tech University the director attempted to bring together the author's perception 39 40 as well as those of the actors to make Old Times an mteresting and thought provoking production. Harold Pinter is a playwright who knows the terror and torment of his audience and brings it to life through silence. SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY Builcman, Katherine H. The Dramatic Worid Of Harold Pinter Its Basis In Ritual. Columbus: Ohio State University Press, 1971. Carlson, Marvin and Shafer, Yvonne. The Plav's The Thing: An Introduction to Theatre, New Yoric: Longman, 1990. Diamond, Elin. Pinter's Comic Play. London: Associated University Press, 1985. Esslin, Maitin. Pinter: A Study Of His Plays. 3rd, ed. London: Eyre Methuen, 1977. Gabbard, Lucina Paquet. The Dream Structure of Pinter's Plavs: A Psychoanalytic Approach. Fairieigh Dickinson University Press, London: Associated University Presses, 1970. Gale, Steven H. ed. Harold Pinter: Critical Approaches. London: Associated University Presses,1986. Gordon, Lois G. Stratagems To Uncover Nakedness: The Dramas Of Harold Pinter. Columbia: University Of Missouri Press, 1969. Hinchliffe, Arnold P. Harold Pinter. Boston: Twayne Publishers, 1981. HoUis, James R. Harold Pinter: The Poetics Of Silence. Carbondale and Ed wards ville: Southern Dlinois University Press, 1970; reprint, London and Amsterdam: Feffer & Simons, Inc., 1971. Pinter, Harold. Old Times. New York: Grove Press, 1971. Quigley, Austin E. The Pinter Problem. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1975. Sakellaridou, Elizabeth. Pinter's Ftemale Portraits: A Smdv Of Female Characters In The Plavg Of Harold Pinter Totowa: Bames & Noble Books, 1988. 41

![The mysterious Benedict society[1]](http://s2.studylib.net/store/data/005310565_1-e9948b5ddd1c202ee3a03036ea446d49-300x300.png)