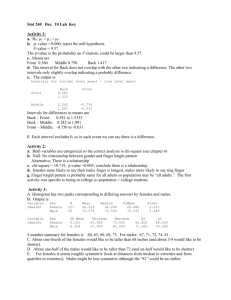

gender differences and fast food preferences among us college

advertisement