Brief for Defendants

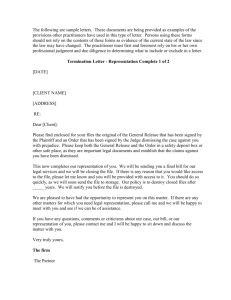

advertisement

To be Argued by: ANN M. ALEXANDER., ESQ. (Time Requested: 10 Minutes) APL-2014-00105 Appellate Division Docket No. CA 13-00896 Onondaga County Clerk’s Index No. 2012-3413 Court of Appeals of the State of New York EILEEN MALAY, Plaintiff-Appellant, – against – CITY OF SYRACUSE, GARY W. MIGUEL, DANIEL BELGRADER, MICHAEL YAREMA, and STEVE LYNCH, Defendants-Respondents. BRIEF FOR DEFENDANTS-RESPONDENTS ROBERT P. STAMEY CORPORATION COUNSEL OF THE CITY OF SYRACUSE Attorney for Defendants-Respondents 300 City Hall 233 East Washington Street Syracuse, New York 13202 Tel.: (315) 448-8400 Fax: (315) 448-8381 Of Counsel: Ann M. Alexander, Esq. August 15, 2014 DISCLOSURE STATEMENT PURSUANT TO RULE 500.1(f) The City of Syracuse is a municipal corporation organized under the laws of the State of New York and has no parents, subsidiaries or affiliates. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page TABLE OF AUTHORITIES .................................................................................. ii PRELIMINARY STATEMENT .............................................................................1 QUESTIONS PRESENTED ....................................................................................4 STATEMENT OF FACTS ......................................................................................5 A. Factual Background ...............................................................................5 B. Procedural History .................................................................................7 ARGUMENT .........................................................................................................12 PLAINTIFF’S COMPLAINT IS TIME-BARRED; PLAINTIFF’S FEDERAL CLAIMS WERE SUMMARILY DISMISSED AND PLAINTIFF FAILED TO COMMENCE THE INSTANT STATE ACTION WITHIN SIX MONTHS OF THE DATE OF JUDGMENT AS REQUIRED BY CPLR § 205(a) ..........................................................12 A. The six-month statutory period to commence a second action pursuant to CPLR § 205(a) should not be forestalled by an appeal unless the appeal is actually taken and a decision is rendered on the merits ..............................................................................................12 B. The case law cited by Plaintiff either supports dismissal of her Complaint as untimely or is inapplicable and should be ignored ......23 C. Plaintiff was not prevented from commencing her state action while her federal appeal was pending ................................................27 CONCLUSION ......................................................................................................31 i TABLE OF AUTHORITIES Cases Page(s) Bender v Peerless Insurance Co., 36 AD3d 1120 (3rd Dept. 2007) ..................... 28 Clark v New York State Office of Parks, Recreation & Historic Preservation, 6 AD3d 1200 (4th Dept. 2004) .......................................................................30 Cohoes Hous. Auth. V. Ippolito-Lutz, 65 AD2d 666 (3rd Dept. 1978) ..........14, 25 Cook v Deloitte & Touche, USA, 13 Misc.3d 1203(A), 824 N.Y.2d 753 (Sup. Ct. 2006) ....................... 18-20, 28 Dinerman v Sutton, 45 Misc.2d 791 (Sup. Ct. 1965) ........................ 17, 20, 22, 25 Gesegnet v Hyman, 285 AD2d 719 (3rd Dept. 2001) ...........................................14 Goldstein v New York State Urban Dev. Corp., 13 NY3d 511 (2009) ..........13, 17 Henkin v Forest Laboratories, Inc., 2003 WL 749236 (SDNY 2003) ..................13 In Re Sean W., 87 AD3d 1318 (4th Dept. 2011) ...................................................28 Lehman Brothers v Hughes Hubbard & Reed, LLP, 92 NY2d 1014, 1016-1017 (1998). .............................................. 14, 15, 23-25 Maki v Grenda, 224 AD2d 996 (4th Dept. 1996) ........................................... 25, 26 Trinidad v New York City Dept. of Correction, 423 F.Supp.2d 151, 169 (SDNY 2006) .........................................................13 ii Statutes 42 U.S.C. §1983 .................................................................................................7, 29 CPLR § 205 ........................................................................ 2, 4, 8, 10, 12-24, 26, 29 CPLR § 3211 .......................................................................................... 2, 10, 27-29 N.D.N.Y., Local Rule 7.1(g) ....................................................................................8 iii PRELIMINARY STATEMENT The facts underlying this action arise out of a lengthy stand-off between Defendants-Respondents, City of Syracuse, Gary W. Miguel, Daniel Belgrader, Michael Yarema and Steve Lynch (hereinafter collectively “Defendants”) and the owner of the building where Plaintiff-Appellant rented an apartment in March 2007. On March 17, 2007, the owner – who also resided in the building – had shot his wife on the lawn of the property and retreated into the building where he held his son and several other relatives hostage. The ensuing stand-off with Defendants lasted for approximately twenty-four hours. During that time, Defendants became aware that Plaintiff resided in the first-floor apartment, but were unable to confirm she was actually there. Defendants ultimately fired gas canisters into the building, including Plaintiff’s apartment, at which time she called 911 for assistance. Although Plaintiff was safely removed from the house, her apartment and personal items were contaminated. Upon entering the building, Defendants discovered the owner had shot and killed himself and his son. Plaintiff originally commenced an action against Defendants in Federal Court, Northern District of New York, on June 6, 2008 (the “Federal Action”). That Federal action was dismissed on Summary Judgment (Hon. Lowe, Magistrate Judge) on September 30, 2011. Plaintiff then moved – albeit untimely – for reconsideration of the summary judgment motion, which was denied in a Decision 1 and Order, dated December 28, 2011. Plaintiff subsequently filed a Notice of Appeal, but she abandoned the appeal and no decision on the merits was ever rendered. Instead, the Second Circuit Court of Appeals dismissed the appeal finding the “case is deemed in default” as of July 10, 2012. Plaintiff commenced the instant action in Supreme Court, Onondaga County, on or about June 25, 2012 – well over six months after the Federal District Court dismissed Plaintiff’s Federal claims and refused to exercise jurisdiction over the remaining state law claims. Defendants filed a pre-answer motion to dismiss pursuant to CPLR § 3211(a) on the grounds Plaintiff’s Complaint was untimely. The Supreme Court (DeJoseph, S.C.J.) granted the motion to dismiss, and a Decision and Order was entered on or about November 29, 2012. In the Decision and Order, the Supreme Court properly concluded that Plaintiff could not benefit from the Savings Statute pursuant to CPLR § 205(a), because she did not commence the action within six months from the date her Federal Action was dismissed. Specifically, the Supreme Court held that the CPLR § 205(a) grace period began to run from the date the original order was entered dismissing Plaintiff’s federal claims, and not from the date the Second Circuit formally dismissed Plaintiff’s appeal due to her own default. Plaintiff appealed the Supreme Court’s Decision and Order, which was affirmed by the Appellate Division, Fourth Department, without a written decision 2 on or about January 3, 2014. Plaintiff then sought leave to appeal to this Court, which was granted on or about May 8, 2014. 3 QUESTIONS PRESENTED 1. Did the Supreme Court err in holding Plaintiff’s Complaint was untimely and that the six-month grace period to commence the instant State Action pursuant to CPLR § 205(a) began to run from the date of entry of the Federal Summary Judgment Order as opposed to the date Plaintiff’s Second Circuit Appeal was formally dismissed after Plaintiff failed to file a brief or appendix and effectively abandoned her appeal? ANSWER: NO. Supreme Court properly held that when a Plaintiff’s federal appeal is dismissed due to the Plaintiff’s own default, then the six-month grace period afforded by CPLR § 205(a) to pursue her remaining state claims begins to run from the date the original order terminated the first action as opposed to the date the appeal was formally dismissed. Plaintiff’s position would allow any plaintiff to improperly extend the six-month grace period simply by filing a notice of appeal and waiting for the appeal to be dismissed as abandoned; such position is not supported by any case law, and runs afoul of the overall intent of the statute of limitations enacted to protect defendants from having to defend stale claims while, at the same time, providing a reasonable period of time which a person of ordinary diligence would bring an action. 4 STATEMENT OF FACTS A. Factual Background In March 2007, Plaintiff was renting a first-floor apartment at 303 Gere Avenue in Syracuse, New York. [R. 69]. Plaintiff rented the apartment from Thach and Sopheap Ros, who owned and resided in another apartment in the house, along with their children. [R. 69]. On March 17, 2007, the Syracuse Police Department (hereinafter the “SPD”) received reports of a shooting and possible hostage situation at 303 Gere Avenue. [R. 69]. SPD personnel, including its Emergency Response Team, responded to that location, where it was initially determined that Thach Ros had shot his wife, Sopheap Ross, in the street. Still armed, Thach Ros then retreated back into his home at 303 Gere Avenue where he had allegedly shot his son, Peter. [R. 69-70]. After SPD arrived, they heard screams from Thach Ros’ daughter-in-law at a window of 303 Gere Avenue. Police were able to evacuate the daughter-in-law and two of Thach Ros’ children from the roof with a ladder. After evacuating these individuals, Thach Ros remained inside the house with his son, Peter. [R. 69-70]. Although SPD were told Thach Ros had shot his son in the head, and were nearly certain the boy was dead, the SPD did not know for certain whether Thach Ros would escalate the situation in some manner. [R. 70, 86]. A stand-off then ensued for approximately the next twenty-four hours. [R. 13, 25]. 5 During this time, SPD became aware that a tenant also resided at 303 Gere Avenue. [R. 71]. SPD were able to obtain a telephone number for Plaintiff and proceeded to try and contact her to determine whether she was in her apartment and needed assistance out. [R. 71]. Unfortunately, and unbeknownst to the SPD, Plaintiff’s telephone was being used as a modem for her computer during that time, and therefore, the only response the SPD received upon calling was a continuous ringing. [R. 71-72]. The SPD did not know Plaintiff was in her home. [R. 13, 71]. Based on concerns of officer safety, the decision was made to deploy CS gas in an attempt to force Thach Ros from the residence. [R. 86]. As the SPD began methodically firing the gas into the building, canisters were also fired into Plaintiff’s apartment since the layout of the house was yet unknown. At that point, Plaintiff used a cell phone to call 911 for assistance. [R. 74-75]. She was immediately contacted by the SPD and safely evacuated from the premises. [R. 75-76]. Plaintiff was taken to an SPD van and offered medical assistance. Plaintiff declined any medical assistance. [R. 76, 91-92]. SPD personnel continued to surround and monitor Thach Ros’ home. The following day, SPD personnel went into the home but had to withdraw when they were fired upon by Thach Ros. [R. 13-14, 26]. Eventually, SPD personnel did enter the premises where they discovered that Thach Ros had taken his own life. [R. 12-13, 26]. 6 SPD subsequently cordoned off the entire building because it was a crime scene. Plaintiff’s vehicle and apartment were contaminated as a result of the gas used during the event. [R. 14, 26]. B. Procedural History On or about June 6, 2008, Plaintiff commenced an action by filing a complaint in the United States District Court, Northern District of New York, against Defendants (hereinafter the “Federal Action”). [R. 48-66]. Therein, Plaintiff asserted four claims pursuant to 42 U.S.C. § 1983, alleging violations of Plaintiff’s constitutional rights under the Fourth, Fifth, and Fourteenth Amendments of the United States Constitution. Plaintiff also asserted one claim for violation of her rights under the New York State Constitution, and four claims of negligence under New York common law. Each of Plaintiff’s claims in the Federal Action arose from Defendants’ alleged actions on March 17, 2007. [R. 48-66]. Prior to asserting an Answer, Defendants sought dismissal of the Federal Action in its entirety for failure to state claims upon which relief could be granted. In a Decision and Order, dated July 14, 2009, the Northern District Court dismissed Plaintiff’s Fifth Amendment claims, all claims against Gary Miguel, and further dismissed all claims asserted against Defendants for violations of Plaintiff’s rights under the New York State Constitution. [R. 27]. 7 After completing extensive discovery, Defendants moved for summary judgment seeking dismissal of Plaintiffs’ remaining claims in their entirety. [R. 27]. On September 30, 2011, the Northern District granted Defendants’ motion for summary judgment and dismissed Plaintiff’s Federal Claims in their entirety (hereinafter the “Summary Judgment Order”). [R. 67-95]. With regards to Plaintiff’s remaining State law claims, the District Court held that “[b]ecause the Court has dismissed all of Plaintiff’s federal claims, it declines to exercise jurisdiction over Plaintiff’s state law claims.” [R. 96]. Since Plaintiff’s state law claims were not dismissed on the merits, she had the option of filing a second action in New York State Supreme Court within six months pursuant to CPLR § 205(a) if she wished to pursue her remaining state law claims. However, instead of timely pursuing an action in New York Supreme Court, Plaintiff chose to file an untimely motion for reconsideration in the Federal Action. [R. 98, 101]. Defendants’ counsel immediately notified the District Court that Plaintiff’s time to file a motion for reconsideration was time-barred pursuant to Northern District of New York, Local Rule 7.1(g). [R. 101]. Plaintiff nevertheless filed a motion for reconsideration on or about November 7, 2011. [R. 104]. Notably, the singular issue presented for reconsideration was the dismissal of Plaintiff’s Federal claim alleging Defendants violated her constitutional rights by allegedly failing to decontaminate Plaintiff’s apartment and personal property. [R. 105]. Plaintiff did not 8 seek reconsideration of the District Court’s refusal to exercise jurisdiction over Plaintiff’s State law claims. [R. 103-114]. The District Court “DENIED” Plaintiff’s motion for reconsideration in its entirety in a Decision and Order, dated December 28, 2011. [R. 103-114]. The District Court specifically held that that “[p]laintiff did not file her motion within fourteen days after the September 30, 2011, order and judgment. Thus, her motion is untimely.” [R.104]. The District Court also concluded Plaintiff’s motion lacked merit and denied the requested relief in its entirety because Plaintiff’s amended complaint failed to “allege facts plausibly suggesting that any individual Defendant violated Plaintiff’s constitutional rights by failing to decontaminate her property.” [R. 114]. The Reconsideration Order did not modify, reverse or otherwise amend the District Court’s previous Summary Judgment Order in any manner. After Plaintiff’s motion for reconsideration was denied, Plaintiff filed a Notice of Appeal with the Second Circuit Court of Appeals on January 27, 2012. See Malay v City of Syracuse, Second Circuit, Dkt. No. 1, Notice of Appeal. Plaintiff indicated in her Pre-Argument Statement (the only papers Plaintiff ever filed with the Second Circuit) that she intended to seek review of the dismissal of her federal claims only. See Malay v City of Syracuse, Second Circuit, Dkt. No. 13, Form C – Pre-Argument Statement. 9 Plaintiff never perfected this appeal. In fact, plaintiff abandoned the appeal completely and no determination on the merits was ever made or entered by the Second Circuit Court of Appeals. [R. 142, 146]. Instead, the Second Circuit dismissed Plaintiff’s appeal as of July 10, 2012, holding the case was “deemed in default” as a result of Plaintiff’s failure to file a brief and appendix. [R. 146]. Almost nine months after Plaintiff’s Federal Action was dismissed and the District Court refused to exercise jurisdiction of Plaintiff’s State law claims, Plaintiff commenced the instant action by filing a Summons and Complaint in Supreme Court, Onondaga County, on June 25, 2012 (hereinafter the “State Action”). [R. 3347]. Defendants immediately moved to dismiss Plaintiff’s Complaint as untimely pursuant to CPLR § 3211. [R. 20-114, 140-145]. In opposition, Plaintiff argued the six-month grace period afforded by CPLR § 205(a) did not begin to run until the Second Circuit Court of Appeals formally dismissed her appeal despite the fact that she clearly abandoned it. [R. 115-138]. The Supreme Court properly rejected this argument holding, among others things, that Plaintiff could not benefit from the later date when her Second Circuit appeal was dismissed because Plaintiff abandoned this appeal and it was never decided on the merits due to the Plaintiff’s own default. [R. 17-18]. Instead, the Supreme Court properly held the six-month grace period began to run from the date of entry of the District Court’s Summary Judgment Order, and 10 Plaintiff’s Complaint was therefore untimely. [R. 17-18]. Plaintiff appealed the Supreme Court’s Decision and Order [R. 3], which was affirmed by the Appellate Division, Fourth Department, without a written decision on or about January 3, 2014. [R. 203]. Plaintiff then sought leave to appeal to this Court, which was granted on or about May 8, 2014. [R. 204-205]. 11 ARGUMENT PLAINTIFF’S COMPLAINT IS TIME-BARRED; PLAINTIFF’S FEDERAL CLAIMS WERE SUMMARILY DISMISSED AND PLAINTIFF FAILED TO COMMENCE THE INSTANT STATE ACTION WITHIN SIX MONTHS OF THE DATE OF JUDGMENT AS REQUIRED BY CPLR § 205(a) A. The six-month statutory period to commence a second action pursuant to CPLR § 205(a) should not be forestalled by an appeal unless the appeal is actually taken and a decision is rendered on the merits. Neither party disputes that the six month tolling provision provided by CPLR § 205(a) was available to Plaintiff after the Federal District Court granted Defendants’ motion for summary judgment on September 30, 2011, dismissing Plaintiff’s Federal Complaint on the merits and declining to exercise supplemental jurisdiction over the remaining state law claims. [R. 67-96]. Indeed, Section 205(a) states, in relevant part, as follows: (a) New action by plaintiff. If an action is timely commenced and is terminated in any other manner than by a voluntary discontinuance, a failure to obtain personal jurisdiction over the defendant, a dismissal of the complaint for neglect to prosecute the action, or a final judgment upon the merits, the plaintiff … may commence a new action upon the same transaction or occurrence or series of transactions or occurrences within six months after the termination provided that the new action would have been timely commenced at the time of commencement of the prior action and that service upon defendant is effected within such six-month period. … (CPLR § 205[a]) (emphasis added). 12 Here, the Federal Summary Judgment Order constituted a final disposition on the merits dismissing each of Plaintiff’s Federal Claims, and the Federal Court declined to exercise jurisdiction over Plaintiff’s remaining State Claims. [R. 6795]. Accordingly, at the time the District Court issued its Summary Judgment Order on September 30, 2011, Plaintiff’s Federal Action was terminated within the meaning of CPLR 205(a), and Plaintiff had the option to commence a state court action with six months. See generally Goldstein v New York State Urban Dev. Corp., 13 NY3d 511, 518-519 (2009); see e.g. Trinidad v New York City Dept. of Correction, 423 F.Supp.2d 151, 169 (SDNY 2006); Henkin v Forest Laboratories, Inc., 2003 WL 749236, *10 (SDNY 2003). However, Plaintiff did not file the instant Complaint within six months of the District Court’s Summary Judgment Order as required by CPLR § 205(a), but instead waited until June 25, 2012, almost nine months after her Federal Action was dismissed. [R. 34]. Accordingly, the Supreme Court properly dismissed the State Action as untimely, holding as follows: “In the Court’s view, the district court’s summary judgment order of September 30, 2011, constituted a final decision on the merits. At that point, plaintiff’s federal action was terminated and plaintiff had the option to commence a state action within six months. Plaintiff failed to do so and, as a result, the present action must be dismissed.” [R. 16-17]. 13 Despite this ruling, as well as the Appellate Division’s affirmance, Plaintiff continues to argue that she was not required to file her State Action within six months of the Summary Judgment Order, but was instead permitted to wait six months from the date her appeal to the Second Circuit Court of Appeals was dismissed – despite the fact that the appeal was dismissed due to her own default after she filed an untimely motion for reconsideration in the District Court. Supreme Court properly rejected this argument and dismissed Plaintiff’s complaint as untimely, and it is respectfully submitted that this Court do the same. 1 It is well settled by this Court that where an appeal is taken as a matter of right, or where discretionary appellate review is granted, the six-month period provided under CPLR § 205(a) does not commence until there is a determination of the appeal. See Lehman Brothers v Hughes Hubbard & Reed, LLP, 92 NY2d 1014, 1016-1017 (1998); see also Cohoes Hous. Auth. V. Ippolito-Lutz, 65 AD2d 666 (3rd Dept. 1978) aff’d. 49 NY2d 961. In Lehman Brothers, this Court succinctly articulated the following with regards to appellate review and the statutory period afforded by CPLR § 205(a): 1 It should also be noted that Plaintiff abandoned before the Appellate Division any argument on appeal that the six-month grace period began to run from the date of the District Court’s Reconsideration Order. As Supreme Court properly noted, there was a final determination on the merits upon entry of the Summary Judgment Order. Plaintiff then filed an untimely motion for reconsideration and the District Court’s Decision on the motion did nothing to alter, amend or otherwise modify its prior determination. Compare to Gesegnet v Hyman, 285 AD2d 719 (3rd Dept. 2001). As such, Plaintiff could not benefit from the later date of the Reconsideration Order to begin the running of the grace period afforded pursuant to CPLR § 205(a). 14 “we, like the Appellate Division, rejected the argument that a party could forestall the commencement of the statutory six-month period merely by continuing to pursue discretionary appellate review. It is not the purpose of CPLR 205(a) to permit a party to continually extend the statutory period by seeking additional discretionary appellate review. By contrast, where an appeal is taken as a matter of right, or where discretionary appellate review is granted on the merits, the six-month period does not commence since termination of the prior action has not yet occurred. Id. (emphasis added). While the undersigned has found no case law from this Court directly addressing the issue presented in this case (i.e., at what point does the six-month statutory period begin to run where an appeal as-of-right is abandoned and no determination on the merits is ever made), it is respectfully submitted that the reasoning which led this Court to reject the plaintiff’s argument in Lehman Brothers, which would have forestalled the running of the statutory period, also applies in this matter. Indeed, Plaintiff and her counsel would like this Court to simply ignore the fact that Plaintiff abandoned her Second Circuit appeal. However, the fact that Plaintiff never filed a record or brief, and simply waited for the Second Circuit to dismiss the appeal on the basis of Plaintiff’s own default is significant. First, as in Lehman Brothers, a plaintiff should not be permitted to forestall the running of the statutory period under CPLR § 205(a) simply by filing a notice of appeal, failing to perfect that appeal and waiting until the appeal is dismissed due to default. Even interpreting CPLR § 205(a) broadly, the legislature could not 15 have intended to authorize a plaintiff to wait around until a federal appeals court dismissed an appeal due to the plaintiff’s own default, then allow an additional six months to commence a state action from the date of default. Such a reading of CPLR § 205(a) could have serious and unintended repercussions and would allow any plaintiff to forestall the running of the statutory period simply by filing a notice of appeal without any intention of perfecting it. Second, since the Federal Appeal in this case was not taken to its conclusion, but was instead dismissed due to the Plaintiff’s default, no determination on the merits was ever entered by the Second Circuit Court of Appeals either affirming or reversing the District Court’s Summary Judgment Order. As a result, the Summary Judgment Order entered in September 2011 remains the only determination terminating Plaintiff’s Federal Action, and dismissing her state law claims. Since CPLR § 205(a) begins to run “within six months after the termination” of the prior action, based on the plain language of the statute, the sixmonth period to commence the instant State Action began when the Summary Judgment Order was entered in the Federal Action. Again, while there is no Court of Appeals case directly on point, there is relevant and analogous case law which supports the lower courts position that the grace period provided by CPLR § 205(a) runs after an appeal taken as a matter of right only if there is a determination of the appeal on the merits. In other words, 16 when a plaintiff files a notice of appeal, but never pursues it to its conclusion on the merits, the termination date for purposes of the six-month grace period runs from the date of the original dismissal order – not the date the abandoned appeal is formally dismissed. For instance, in Dinerman v Sutton, a plaintiff’s action was dismissed for legal insufficiency. Dinerman, 45 Misc.2d 791 (Sup. Ct. 1965). After filing another action in State Court, the defendant filed a pre-answer motion to dismiss arguing, among other things, that the plaintiff’s second complaint was untimely. Id. The defendant argued that even though the plaintiff appealed the dismissal of the earlier action, the second action was not saved because the appeal was dismissed eight months after the notice of appeal was filed without any decision rendered on the merits. Id. at 792. The Supreme Court agreed and held that “[t]he grace period of CPLR 205 commences from the date of determination of an appeal on the merits. To apply this rule to a dismissed appeal would be to permit a plaintiff to extend his own time to commence a new action in every case by merely filing a notice of appeal.” Id. (emphasis added); See also Goldstein v New York State Urban Dev. Corp., 13 NY3d 511, 543, fn. 4 (2009) (concurring opinion) (“Professor Siegel observes that ‘while the six-month period supplied by CPLR 205[a] will be measured from an appellate determination if the earlier action went through an appellate stage, this applies only where an appeal was available and 17 was in fact taken.’”). Since the plaintiff failed to commence the second action within six months after the first action was dismissed for legal insufficiency, the second action was untimely. Id. Similarly, in Cook v Deloitte & Touche USA, the plaintiff’s federal claims were summarily dismissed on October 4, 2005, and the federal court declined to exercise jurisdiction over the remaining state claims. Cook, 13 Misc.3d 1203 at *2, 824 NYS2d 753 (Sup. Ct. 2006). The plaintiff then filed a notice of appeal with the Second Circuit Court of Appeals. However, the plaintiff did not seek review of the District Court’s refusal to exercise supplemental jurisdiction over the plaintiff’s state law claims in his brief or otherwise. The plaintiff then commenced a state court action on April 28, 2006, over six months after her federal action was dismissed. Id. The defendants in Cook moved to dismiss the plaintiff’s complaint as untimely. Id. at *2-3. Specifically, as here, the defendant argued that the sixmonth grace period afforded to the plaintiff under CPLR § 205(a) began to run on October 4, 2005, when final judgment was entered in the Federal Court Action. The defendant argued that the plaintiff’s pending appeal should not extend the sixmonth statutory grace period because “when no appeal is taken from the dismissal order, or when a notice of appeal is filed from a dismissal order but never prosecuted on the merits, the ‘termination date’ on which the grace period begins 18 to run is the date on which the dismissal order is entered.” Id. at *3. As here, the plaintiff in Cook opposed the motion claiming that (1) the Federal Action had not yet terminated for purposes of CPLR § 205(a) because the federal appeal was still pending; (2) the legislature did not intend to require pendent state claims, dismissed without prejudice, to be tried concurrently with federal court claims; and (3) CPLR § 205[a] is to be “liberally construed.” Id. at *4-5 Even though the plaintiff appealed the dismissal of the federal claims, the Supreme Court in Cook held that the State law claims were “terminated” for purposes of CPLR § 205(a) when the original dismissal order was issued by the District Court on October 4, 2005. Since the plaintiff chose not to appeal the District Court’s decision not to exercise supplemental jurisdiction over the state claims, the Supreme Court held the plaintiff’s pending federal appeal did not forestall the time six-month statutory period to commence a state action. Id. at *910. With regards to the plaintiff’s arguments, the Supreme Court specifically stated as follows: The possibility that plaintiff may be prejudiced due to collateral estoppel, by a requirement that [he] file an action within six months after dismissal, while the federal action is pending, is not without basis. However, any prejudice from the collateral estoppel effect upon facts that might be determined in federal court was waived when plaintiff deliberately declined to appeal the dismissal of his nonfederal claims, thereby necessitating the commencement of 19 the instant action in State Court to preserve such claims. Similarly, that plaintiff may be forced to “split” non-federal claims from federal claims, and file non-federal claims in State Court after their dismissal, while a federal action is pending, is a consequence of plaintiff's decision to appeal the dismissal order in part. Once plaintiff exercised his option to abandon his non-federal claims in the Federal Action, he was obligated to commence a new action upon such claims within six months of entry of judgment dismissing such claims, and plaintiff cannot not be heard to be prejudiced by the dual litigation of the facts underlying each action. Id. at * 9 (internal citations omitted). In fact, the Supreme Court stated that allowing the plaintiff to file a state action six months after her federal claims were determined on appeal “would undermine the purpose of the statute of limitations” which were enacted to “afford protection to defendants against defending stale claims after a reasonable period of time has elapsed during which a person ordinary diligence would bring an action.” Id. Moreover, the Court reiterated as follows: “The Court is mindful that CPLR 205 is an ameliorative provision, to be construed liberally with due consideration given to the purpose of the limitation period affected However, to adopt plaintiffs’ position would permit him to file his non-federal claims in State Court after the disposition of the Federal Action, in which such non-federal claims have been expressly abandoned, and such position flies in the face of the underlying, overall intent of the statute of limitations.” Id. at *10 (internal citations omitted). Here, as in Dinerman and Cook, Plaintiff’s Federal Action was terminated on September 30, 2011, when her Federal claims were dismissed and the District 20 Court declined to exercise jurisdiction over her State claims. As in Cook, Plaintiff never sought to appeal the District Court’s decision declining to exercise jurisdiction over Plaintiff’s remaining State law claims. Despite Plaintiff’s claim to the lower courts, Plaintiff’s Pre-Argument Statement does not identify any intention to appeal the dismissal of her state law claims. See Malay v City of Syracuse, Second Circuit, Dkt. No. 13, Form C – Pre-Argument Statement. Instead, Plaintiff extensively outlines the federal claims she intended to pursue in her Federal appeal. As such, even before the Second Circuit Court of Appeals dismissed the appeal, Plaintiff had effectively abandoned her state law claims in the Federal Court. Furthermore, and contrary to Plaintiff’s assertion, the fact Plaintiff never perfected her Second Circuit Appeal and abandoned it is of enormous consequence. Indeed, the Second Circuit dismissed the appeal “effective July 10, 2010,” holding the case was “deemed in default” as the result of Plaintiff’s failure to file a brief and appendix; no determination on the merits was ever made or entered. [R. 146]. Consequently, the Supreme Court held and it is submitted that this Court should affirm that “when an appeal is abandoned and dismissed on account of a default, the CPLR 205 grace period begins to run from the date the original order of appeal was entered. In this case, the September 2011 [Summary Judgment] Order.” [R. 18]. To permit otherwise would allow any “plaintiff to 21 extend his own time to commence a new action in every case merely by filing a notice of appeal.” Dinerman v Sutton, 45 Misc.2d at 792. Plaintiff’s first “question presented” is noteworthy in this regard: Is a plaintiff required to litigate an appeal as of right to its terminus before invoking the grace period of CPLR § 205(a) and filing an action in state court, or can that plaintiff choose to file the state court complaint during the pendency of the appeal and discontinue the appeal? Answer: The longstanding history and interpretation of CPLR § 205(a) gives a diligent plaintiff the right to pursue an appeal to its terminus or discontinue that appeal in order to pursue a valid state cause of action. A plaintiff is not required to pursue an appeal to its end only to preserve an otherwise legitimate and timely state cause of action. Appellant Brief, p. 1. Defendants do not disagree with the answer provided by Plaintiff to the question presented above. Instead, Defendants disagree with Plaintiff’s contention that she acted as a diligent plaintiff. Plaintiff certainly had the right to pursue her appeal as-of-right until a determination was made on the merits and then, pursuant to CPLR § 205(a), commence a state action within six months. Plaintiff also had the right to discontinue her federal appeal as-of-right and pursue her remaining claims in a second state action. However, Defendants maintain that by abandoning her Federal Appeal, she should not benefit from the later date that her appeal was formally dismissed by the Federal Court for the commencement of the six-month 22 grace period afforded by CPLR § 205(a). Such an interpretation of the statute goes directly against this Court’s reasoning as articulated in Lehman Bros. and its progeny. It is respectfully submitted that this Court find that the grace period afforded by CPLR § 205(a) should only be extended if there is a determination on the merits of an appeal taken as a matter of right. The Plaintiff’s choice to abandon her Second Circuit Appeal and failure to file the instant Complaint within six months after the Summary Judgment Order was entered is without excuse, and this Court should affirm dismissal of the Supreme Court’s Order dismissing the Complaint as untimely as a matter of law. B. The case law cited by Plaintiff either supports dismissal of her Complaint as untimely or is inapplicable and should be ignored. The case law relied on by Plaintiff is either misplaced or inapplicable and should be ignored by this Court. Indeed, Plaintiff did not – and cannot – cite a single case where a court held that the six-month grace period under CPLR § 205(a) began to run from the date an appeal was dismissed due to the Plaintiff’s own default. No such case law exists because, as outlined above, such a proposition flies in the face of the intent and purpose of the statute of limitations and CPLR § 205(a). While Plaintiff relies extensively on this Court’s decision in Lehman Bros. v Hughes, Hubbard & Reed, it is respectfully submitted that this case does little to 23 sustain Plaintiff’s argument and, in fact, as noted above, supports dismissal of Plaintiff’s Complaint as untimely. Lehman Brothers, 92 N.Y.2d 1014 (1998). In Lehman, the plaintiffs commenced an action in a Texas District Court, which was dismissed for lack of personal jurisdiction on December 16, 1992. Id. at 1015. In stark contrast with the instant matter, the plaintiffs in Lehman pursued an appeal as a matter of right, and the District Court’s decision was affirmed on the merits on June 1, 1995. Id. at 1016. There is absolutely no indication in Lehman that the plaintiffs abandoned their non-discretionary appeal or that the appeal was dismissed due to the plaintiffs’ default. In fact, after exhausting their non-discretionary appeal and obtaining a determination on the merits, the plaintiffs continued to seek further discretionary appellate review from the Texas Supreme Court, and petitioned the United States Supreme Court for writ of certiorari, which was denied on June 10, 1996. Id. After the petition to the Supreme Court was denied, the plaintiffs filed an action in New York on July 11, 1996. Id. In dismissing the plaintiff’s second action commenced in New York, this Court articulated the rule which has been repeatedly sustained in courts throughout New York State: that the purpose of CPLR § 205(a) is not to permit a party to continually extend the statutory period simply by taking appellate action, but to allow a plaintiff to pursue an appeal as-of-right without fear of losing the ability to commence a second action after a decision is rendered on the merits 24 by the appellate court. Id. at 1016-1017. As previously outlined above, the very same reasoning which led this Court in Lehman to prohibit a plaintiff from extending the six-month grace period “merely by continuing to pursue discretionary appellate review” should be applied to a plaintiff who chooses to abandon an appeal taken as a matter of right. Id. at 1016. To be sure, if Plaintiff’s position were adopted, then any plaintiff could “forestall the commencement of the statutory six-month period merely” by filing a notice of appeal, failing to perfect such an appeal, and waiting for the appellate court to dismiss the case as abandoned. Id.; see also Cohoes Housing Authority v Ippolito-Lutz, 65 AD2d 666, 667 (3rd Dept. 1978) (“As noted by Special Term in the case of Dinerman v Sutton, it is not the purpose of the statute to permit a party to extend the time to commence a new action by merely taking appellate action). Only if there has been a determination of an appeal on the merits should the six-month grace period be extended. Again, Plaintiff has not cited a single case or legal authority supporting her position to the contrary, which amounts to nothing more than an attempt to circumvent the applicable statute of limitations, designed to protect defendants from having to defend stale claims while also providing a reasonable time which a person of ordinary diligence would bring an action. Plaintiff’s position should be ignored and her Complaint dismissed as untimely. Finally, Plaintiff argues that the Appellate Division, Fourth Department, 25 failed to follow its own precedent set in Maki v Grenda when it affirmed dismissal of her Complaint. Maki, 224 AD2d 996 (4th Dept. 1996). However, Plaintiff’s reliance on this case is misplaced. In Maki, the Federal District Court in an Order entered October 19, 1993, dismissed the plaintiff’s federal and state law claims unless the plaintiff repleaded her RICO claims within thirty (30) days of the Order. Id. Plaintiff did not replead her RICO claim, and her Federal Action was therefore terminated as of November 18, 1993. Id. The plaintiff then commenced a new action in state court on April 21, 1994. Id. at 997. The Fourth Department held the plaintiff timely commenced the state action pursuant to CPLR § 205(a). Id. The procedural history in Maki is simply not analogous to the instant matter. To be sure, in contrast to Maki, the Northern District of New York dismissed Plaintiff’s Federal Action on September 30, 2011. Unlike in Maki, there were no conditions, qualifications, stipulations or otherwise placed on the Summary Judgment Order issued by the District Court. Accordingly, and in stark contrast to Maki, as of September 30, 2011, Plaintiff’s Federal Action was terminated and Plaintiff had six months to commence a new action pursuant to CPLR § 205(a). Likewise, and in contrast to Maki, when the Second Circuit provided a firm deadline for Plaintiff to file her brief and appendix, there was already a Decision and Order terminating her Federal Action. Plaintiff should not benefit from the date her appeal was formally dismissed when she was the one who chose to 26 abandon the appeal, there was already an Order from the District Court terminating her Federal Claims which was not affirmed, amended or reversed by the Second Circuit’s Order, and the power to file a state action within six months of the Summary Judgment Order was completely within her control. C. Plaintiff was not prevented from commencing her state action while her federal appeal was pending. Plaintiff continues to make the illogical argument that if she is not afforded six months from the date her appeal was dismissed, she is handcuffed into following one of two paths: (1) following through with her federal appeal until there was a decision on the merits, and then filing the State Action, or (2) filing a concurrent action in state court which would be subject to dismissal pursuant to CPLR 3211(a)(4). On its face, Plaintiff’s argument is utterly misleading. First, Plaintiff completely glosses over the fact that she had six months from the Summary Judgment Order to decide whether to pursue a Federal Appeal to its conclusion or to start a State Action. Six months is certainly a reasonable period of time for a diligent plaintiff to determine whether an appeal has merit. Defendants should not be penalized for Plaintiff’s decision to wait more than six months after the Summary Judgment Order was entered to decide her Federal Appeal lacked merit and that she would not pursue it. Plaintiff had plenty of time to make the decision to abandon her federal appeal and commence a state action. 27 Moreover, Plaintiff’s claim that by filing a state action before her Federal Appeal was dismissed would have subjected her to a motion to dismiss pursuant to CPLR 3211(a) for having two concurrent claims is completely meritless. First, as an initial matter, Plaintiff did not argue this issue in opposition to Defendants’ motion, but raised this issue for the first time during oral argument before the Supreme Court. The issue was raised upon questioning by the Supreme Court Justice and it is respectfully submitted that this Court not consider this argument on appeal. See Bender v Peerless Insurance Co., 36 AD3d 1120 (3rd Dept. 2007) (Appellate Division would not consider issue raised during oral argument in Supreme Court); See generally In Re Sean W., 87 AD3d 1318, 1320 (4th Dept. 2011) (“An issue may not be raised for the first time on appeal ... where it ‘could have been obviated or cured by factual showings or legal countersteps' in the trial court”). Nevertheless, and contrary to Plaintiff’s suggestion, nothing prevented her from commencing her State Action within the six months after the Summary Judgment Order was entered, while at the same time determining whether to pursue her Federal appeal. Indeed, the fact that “plaintiff may be forced to ‘split’ non-federal claims from federal claims, and file non-federal claims in State Court after their dismissal, while a federal action is pending, is a consequence of plaintiff’s decision to appeal the dismissal order in part” and then abandon the 28 appeal altogether. Cook v Deloitte & Touche, USA, 13 Misc.3d 1203(A), * 9. Furthermore, CPLR 3211(a)(4) permits dismissal of a state action only if another action is pending between the parties “for the same cause of action.” There is no doubt that Plaintiff’s state law claims sound in common law negligence, while her Federal claims, pursuant to 42 U.S.C. § 1983, alleged violations of her Constitutional rights. These are certainly not “the same cause[s] of action.” CPLR § 3211(a)(4). However, even if Supreme Court were to consider them the same for purposes of a CPLR 3211(a)(4) motion, the Court would have been under no obligation to dismiss the action and had discretion to craft an order “as justice requires.” Id. Finally, Plaintiff is attempting to argue both sides of the coin with this argument. Indeed, it is disingenuous for Plaintiff to argue on the one hand, that she could not pursue concurrent state and federal actions for fear of dismissal under CPLR 3211(a)(4), while on the other hand argue that her Federal Action was not yet terminated for purposes of CPLR § 205(a) on the date she filed her Complaint in State Court because her appeal was not formally dismissed yet. This argument should be ignored. At the moment the Summary Judgment Order was entered, Plaintiff had three options at her disposal: (1) appeal the District Court’s Summary Judgment Order and commence a State Action within six months after a determination on the 29 merits of the federal appeal; (2) commence a new action in Supreme Court within six months of the Summary Judgment Order after deciding the federal appeal lacked merit; or (3) pursue an Appeal of the Federal claims to the Second Circuit and commence an action in Supreme Court within six months of the Summary Judgment Order to pursue the state law claims. Plaintiff had ample time to pursue any one of these options. In sum, Plaintiff’s failure to file the instant Complaint in Supreme Court until June 25, 2012 – nine months after the Summary Judgment Order was entered in Federal Court – is without excuse given “the fact that the ability to comply was completely within [her] control.” Clark v New York State Office of Parks, Recreation & Historic Preservation, 6 AD3d 1200, 1201 (4th Dept. 2004). This Court should therefore affirm the lower courts decisions and find Plaintiff’s Complaint untimely as a matter of law. 30 CONCLUSION For the foregoing reasons, the Decision and Order of the Supreme Court and Order of the Appellate Division, Fourth Department, should be affirmed, together with such other and further relief that this Court deems just and proper. Dated: August 14,2014 ROBERT STAMEY, ESQ. Corporation Counsel Attorney for Defendants 300 City Hall Syracuse, New York 13202 315.448.8400 By: 31 Ann Mag arelli Alexander Assistant Corporation Counsel

![[2012] NZEmpC 75 Fuqiang Yu v Xin Li and Symbol Spreading Ltd](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/008200032_1-14a831fd0b1654b1f76517c466dafbe5-300x300.png)