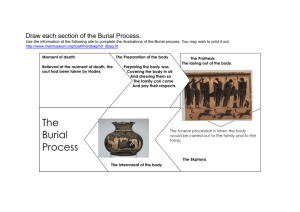

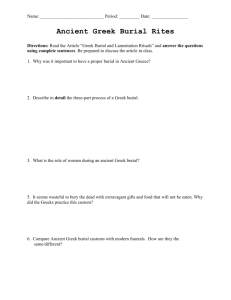

DEATH AND BURIAL RITUALS AND OTHER PRACTICES AND

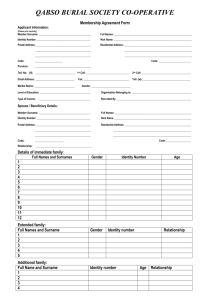

advertisement