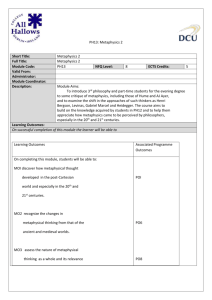

Problems Of Metaphysical Philosophy

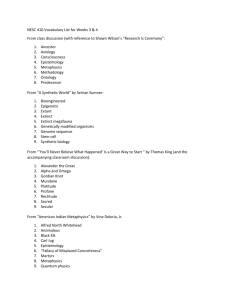

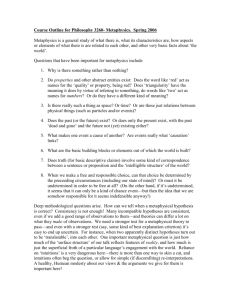

advertisement