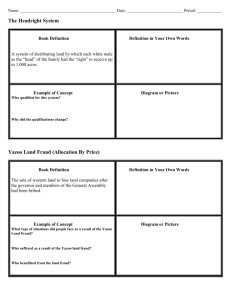

Occupational Fraud - Certified General Accountants Association of

advertisement