Tea Industry Strategic Cost Management: Value Chain Analysis

advertisement

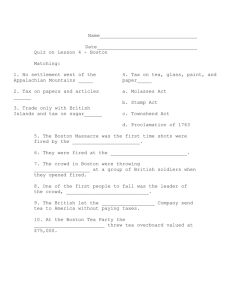

Strategic Cost Management of Tea Industry: Adoption of Japanese Tea Model in Developing Country Based on Value Chain Analysis Sheikh Mohammed Rafiul Huque Abstract The products of the agriculture industry occupy a major portion of international trade. Export of agricultural commodities from developing countries consists of tropical beverages (tea, coffee, cocoa) and other agricultural products such as, bananas, sugar, oilseeds and natural rubber. Beverage like tea comprises a major fraction of the total export of the agricultural products of the Asian countries. Tea industries in the developing countries of Asia are facing huge competition. There also exists inefficiency in the value chain management in the tea industry especially related to land management and plucking efficiency and manufacturing cost. This in fact hinders the growth of this industry. Value chain analysis is one of the main components of strategic cost management. That is why the objective of this paper is to investigate the structure of value chain of the tea industry and associated problems in the developing countries. This paper attempts to find a strategic solution examining the strategic accounting model adopted by the developed countries like Japan. It examines and compares the value chain models that are adopted by the tea industries of Bangladesh and Japan. It has been observed that tea estate managers of Bangladesh are reluctant to maintain tea bushes which actually cut down the level of production and create anomaly in the value chain and provide less yield and low price. It is observed from the analysis that age of tea bushes has significant influence on production and young bushes have very significant influence on production of tea. Bangladesh tea industries possess 82% of the tea plantation area which has mature, old and very old bushes. The old bush plants comprise 42% of total tea producing area. The low yield tea estates possess large number of old bushes. About 40% of the tea estates of the country produce less than 1,000 kg. tea per hectare. About 50% of these low yield tea gardens produce less than 600 kg. tea per hectare. If the low yield gardens had more young bushes, production would increase to 3,818 kg./hectare if other variables remain constant. On the other hand, Japanese tea industries observe a very good operating result by introducing smallholding farmers cooperative model. Strategic cooperative alliance model developed in this study in the light of Japanese cooperative model can help the poor performing gardens of Bangladesh to device an appropriate strategy. This model can help to avert the risks associated with the management of bushes. The firms can use funds of the cooperative for managing bushes and modifying the manufacturing unit. It is understood that the adoption of this model by the tea industries of Bangladesh will enhance tea production significantly. It is also found from cost analysis that SCA gardens will get higher profit after the implementation of SCA model. Key words: Strategic cost management, value chain analysis, smallholding farmers cooperative association, strategic cooperative alliances (SCA) gardens, strategic growers, target costing, tea area, bush management 56 (562) 横浜国際社会科学研究 第 11 巻第 4・5 号(2007年 1 月) Introduction The agriculture industry occupies a major portion of international trade. In recent years, though many countries are shifting towards secondary activities or industrial activities, agro-based industry still plays a very significant role in their economy. The agriculture products of the developed countries mainly comprise food grains like wheat, rice and coarse grains. These commodities comprise a sizeable portion of their export. Developing countries, on the other hand, export agricultural commodities such as, tropical beverages (tea, coffee, cocoa), bananas, sugar, oilseeds and natural rubber. Malaysia is the largest producer and exporter of palm oil and occupies third position in rubber production. Sugar is the main export items of Mauritius, which comprises about 56% of aggregate output. Tea export markets of world are mainly dominated by China, India, Sri-Lanka and some other Asian countries like Bangladesh, Indonesia. On the other hand, South American countries hold the lion share of coffee market. However, in Fig. 1 it can be observed that trade balance of agriculture products in the developing countries is very significant in the area like fruits and vegetables, tea, coffee and cocoa. Besides, these products are facing huge price competition due to almost constant demand. This may be due to their low population growth. A reverse situation can be observed in cereal consumption in the developing countries. Demand for cereal in the developing countries fluctuates due to the scarcity of foods. An introduction of an effective value chain management system with an emphasis on strategic cost management could help the developing countries to secure a sizeable export market share with proper brand image. Literature review Shank and Govindarajan (1993) state that strategic cost management results from a blending of value chain analysis, strategic positioning analysis and cost driver analysis. Among these three core concepts, value chain analysis occupies a significant influence on other concepts of strategic cost management. Porter (1985) introduces the concept of value chain for the strategic improvement of firms or industry. This concept is further developed by Shank and Govindarajan (1992, 1993). It is observed that the core idea of value chain is linked to the set of value creating activities all the way from basic raw material sources to component supplier through the ultimate end-use product delivered to the final consumers hands. Shank and Govindarajan (1993) mention that if the value chain can be expressive, strategic decision can be made more easily basing on the understanding of the firm s competitive advantage. Porter (1980) states that the basic choice of a business to compete either by having lower cost (cost leadership) or by offering superior products (product differentiation). These two approaches seek very different conceptual frameworks (Dess and Devis, 1984; Gilbert and Strebel, 1987; Hall, 1980; Hambrick, 1983). The introduction of cost leadership or differentiation strategy depends on managerial decision making and the nature of business. The introduction of cost leadership strategy in the commodity business during the mature stage of business seeks careful analysis to attain the target cost. In this situation, proper setting of target cost can help the firm to secure a position in the industry. Several studies have focused on strategic cost management especially value chain concept and target costing concept of the manufacturing and service industries. Chen et. al. (1997) do research on US based Japanese subsidiaries and they try to find out practice of accounting system in those subsidiaries. The study concludes that US based Japanese firms practice similar management accounting methods of target costing, value engineering, variable costing and strategic adoption of traditional methods such as standard costing and budgeting like Japanese use the concept of activity based costing and internal rate of return to evaluate the main firms. This study also concludes that US based Japanese firms are also influenced by US firms to adopt the concept of activity based costing and internal rate of return to evaluate the capital investment projects. Shank (1996) focuses on conventional Net Present Value (NPV) framework and relates this concept to strategic cost Strategic Cost Management of Tea Industry (Sheikh Mohammed Rafiul Huque) 50 Cereals and preparations Tea, coffee, cocoa 20 Fruits and vegetables −20 2000 1999 1998 1997 1996 1995 1994 1993 1992 1991 10 1990 US$billion (current price) 30 0 57 Livestock 40 − 10 (563) Natural rubber Sugar Bananas −30 Oil corp products −40 Year Figure 1: Trade balance of developing countries Source: Bruinsma (2003) management for decision making purpose. He does an in-depth study on US firms and he gives suggestion based on strategic cost management issues like value chain analysis, cost driver analysis and competitive advantage analysis. Kato (1993) concentrates on target costing approach in Japanese companies with a motive of cost reduction. He explains that information system is necessary for the adoption of target costing philosophy. Li and Whalley (2002) focus on telecommunication industry s deconstruction and reconsolidation from transaction cost perspective and suggest how this can be managed. Maitland et. al. (2002) study the European market for mobile data and possible form of the industry wide value creation. On the other hand, Chang and Hwang (2002) undergo an intensive study on US and Hong Kong manufacturing and service industry concentrating on value chain cost analysis. Strikingly, no study was done on agriculture industry, especially on tea industry, with a focus on the strategic cost management. Hazarika and Subramanian (1999) explain the technical efficiency of production factors in Assam tea industry in India using Stochastic Frontier Production Function Model. Their study concentrates on the productivity and production factors. This study does not adopt a value chain method, which is generally thought as an essential analytical method for tea industry. Ariyawardana (2003) in an intensive study on value added tea producers in Sri Lanka examines the sources of competitive advantage and studies how it relates to the performances of the tea growers. His study provides a deep understanding of this issue from the management point of view but fails to appraise the value chain and strategic solutions. Objectives and methodology The main objective of this paper is to find out the value chain system of the tea industry of the developing countries and associated problems and side by side attempts to underscore the strategic solution in the light of the strategic accounting model of the developed countries. This paper will further focus on the issues which affect the developing countries tea industry and attempt to find an alternative solution to the problem. Moreover, this paper also focuses on target costing approach which is one of the cost management tools. Two countries, such as Bangladesh (a developing country) and Japan (a developed country) are selected as study areas. Primary data for this study were collected through personal interview from two Japanese Tea Cooperative Associations in Shizuoka prefecture and also from Japanese Tea Research Institute. Secondary data was collected from Japanese Tea Industry Association. Data on structure of value chain in Bangladesh and their associated problems were 58 横浜国際社会科学研究 第 11 巻第 4・5 号(2007年 1 月) (564) collected from Bangladesh tea industries. These data were collected through personal interview from four tea estates in Bangladesh. These tea estates were selected based on ownership of these tea estates and level of performance. Besides, cost related data were collected from nineteen tea estates based on their level of performance. In addition to these, data on tea production, age of bush, price and yield of tea were collected from Bangladesh Tea Board, Bangladesh Tea Association and from reports prepared by the organization of tea auction market in Bangladesh. Background of tea industry and general problems Use of tea started in 2737 BC when the Chinese Emperor, Shen Nong drank hot water with a mixture of dried leaves accidentally from a tea plant unknown at that time. The concept of tea later on moved to Japan (An Environmental Educational Program of the Prague Post Endowment Fund, 2003). Until now the Japanese people remember a Buddhist priest, named Yeisei, as the Father of Tea in Japan, for his contribution to the spread of tea drinking habit to the Japanese. Gradually, tea drinking has become a ritual in Japan. This habit later on had spread to Europe by the Dutch and English people (The History of Tea, 2006). During the British regime plantation of tea spread in India, Sri Lanka and Bangladesh. The colonial British administration started tea plantation in the Indian subcontinent at the beginning of nineteenth century. Gradually tea industries of the sub-continent have become a major producer of tea of the world. According to a recent report, India, Bangladesh and Sri Lanka account for 55% of world production of tea (社団法人日本茶業中央会, 平成18年).In recent years the dominance of these countries in the world tea market declines as some other countries like Kenya, Indonesia, Vietnam, and Malawi are coming up with good quality tea with quite competitive price. At the global level, tea industries is facing the problems such as rise of production cost, market stagnancy and sometimes fall of price. The tea market observes a stagnant period in the recent years as the world demand and supply gap is not large. Sometimes the supply of tea becomes too much and which in turn dulls the market situation. For this reason, the present world tea industry is facing competition in quality production. The average market price was US $1.35 in 1992 and this price dropped to US $1.24 during 2002 (International Tea Committee, 2003). World tea industry scenario: Production and export Major tea production in the world is limited to only few countries and among them China and India occupies a major portion of the production share (28% and 20% respectively). Kenya, Sri Lanka, Turkey, Indonesia and Japan produce about 3% to 10% of the total share of production. In addition, Bangladesh, Malawi and Argentina contribute to some extent to this industry with a small share of around 2% for each country (社団法人日本茶業中央会,平成18年). In Fig. 2 the trend of tea production of the major producing countries of the world are shown. It can be observed that the production of tea in China, India, Kenya, Sri-Lanka and Vietnam are growing steadily with minor fluctuations. Sri Lanka leads with 19% export market share and China and Kenya hold second position with a 18% of the market share. India, Vietnam, Indonesia and Argentina on the other hand, occupy 11%, 6% and 4% export share respectively. Bangladesh has less than 1% of export market share and it seems that its export is gradually declining (社団法人日本 茶業中央会,平成18年). Tea industry and its value chain: A comparison of developed and developing countries There are two major types of tea: Green tea and black tea. The process of production of the green tea is quite different from black tea. Steaming of green leaves is needed after the withering stage of green leaves. The process of production of green tea should skip the fermentation stage just to prevent oxidization. The oxidization process turns the Strategic Cost Management of Tea Industry (Sheikh Mohammed Rafiul Huque) 1,000 Bangladesh Malawi Tanzania Argentina China India Indonesia Sri LankaYear Year Indonesia Sri Lanka 1980 Japan Sri Lanka Turkey Turkey Vietnam Japan 2005 Japan Vietnam 2005 Vietnam 19952005 1995 1995 1980 1980 1980 Kenya Bangladesh Kenya Malawi Bangladesh Tanzania Malawi Argentina TanzaniaChina India Argentina Kenya Indonesia Kenya Bangladesh China SriBangladesh Lanka Malawi Malawi India Turkey Tanzania Tanzania Japan Argentina Indonesia Argentina China Vietnam Sri Lanka 2005China India India Turkey Indonesia1995 1000 ton Turkey Japan 59 Kenya Kenya 900 1,000 1,000 900 800 900 800 1,000 800 700 700 900 700 600 600 800 600 500 500 1000 ton 700 500 400 600 400 400 300 300 1000 ton 500 300 200 200 400 200 100 300 100 200 100 100 - (565) Year Vietnam 2: Majorcountries tea producing countries Fig 2: Major teaFig producing Bangladesh Kenya Malawi Bangladesh Tanzania Malawi Argentina Tanzania China Argentina India China Indonesia India Sri Lanka Indonesia Turkey Sri Lanka Japan Turkey Vietnam Japan Vietnam Fig 2: Major tea producing countries Figure 2: Majortea teaproducing producing countries Fig 2: Major countries 300 250 Malawi 200 Bangladesh 150 1000 ton 100 England China Vietnam Kenya Sri Lanka India Indonesia Argentina Bangladesh Tanzania Malawi 2000 1980 Year 1990 50 0 Tanzania Argentina Indonesia India Sri Lanka Kenya China Vietnam England Figure 3: Major tea exporting countries color of tea leaves into brown. For this reason the color of processed green tea is green. On the other hand, black tea possesses nice flavor and light brown color due to the effect of oxidants, which makes tea leaves brown (Chaudhury, 1989). Besides, to prevent oxidization special type of processing, handling and storage are needed for green tea. Japanese tea industry Background of Japanese tea industry Green tea occupies a substantial portion of Japanese tea industry and it is harvested four times in a year. Each harvesting season has its name. In Japanese language ichibancha, nibancha, sanbancha, yonbancha, mean as first pluck, second pluck, third pluck, and fourth pluck respectively. The first plucking season of green leaves is April May. This harvesting period is called ichibancha and this type of tea is considered as the best quality tea in Japan. Moreover, ichibancha occupies an important status in Japanese tea industry due to the good price and large quantity of production. 横浜国際社会科学研究 第 11 巻第 4・5 号(2007年 1 月) (566) 20,000 2,500 18,000 Production of Shizuoka Price Production in ton 16,000 2,000 14,000 12,000 1,500 10,000 8,000 1,000 6,000 4,000 Price in Yen 60 500 2,000 - First tea Second tea Third tea Fourth tea Tea plucking cycle Figure 4: Production and price comparison of Japanese tea The quantity of production reduces gradually from nibancha (June) to yonbancha (September October) periods. Due to this reason, most of the farmers attempt to capitalize their investment during the first pluck time (Hibiki-en, 2006). Fig. 4 depicts the production and price of tea of the largest tea producing area of Shizuoka prefecture in Japan. This prefecture produces 45% of Japanese tea. It can be seen that the price and quantity of production of Japanese green tea remain high during the first pluck. Price gradually declines from 2,327 yen to 1,117 yen from first to second pluck (社団 法人日本茶業中央会,平成18年). From the graphical analysis it can be concluded that the tea gathered from the first tea plucking (ichibancha) comprises lion share of the tea production. Value chain structure of Japanese tea industry The value chain of Japanese tea industry begins from tea farmer and tea processing plant. It belongs to a group of farmers who runs the business with cooperative farming system. The farmers pluck green leaves depending on the capacity of the processing plants. Managers actually decide how much a farmer should pluck and this decision is taken on the basis of the capacity of production of the manufacturing plant on a specific day. The manufacturing plants process the green leaves up to aracha1) and agents keep in touch with the processing plant to fix the price and rank the quality of aracha. The agents keep contact with the processing companies/distributors and also the cooperative farming associations who sell aracha. The distributors process aracha into final green tea, then grade them and finally sell them to retailers (Fig. 5). Bangladesh tea industry Background of Bangladesh tea industry Tea is a major cash crop as well as a consistent export earner of Bangladesh. The structure of industry of the country differs from Japanese tea industry. The garden size and management structure are quite different in Japan. In Bangladesh, on average the area of a tea estate is around 337 hectare. At present there are very few newly established smallholding tea gardens operating in the north-western part of Bangladesh. They have very insignificant contribution to the tea industry of Bangladesh. The first tea garden was established in 1857 at Malnicherra, two miles away from Sylhet town, situated in the north-eastern part of Bangladesh. The British companies were the pioneer of tea plantation in Strategic Cost Management of Tea Industry (Sheikh Mohammed Rafiul Huque) (567) 61 Figure 5: Shizuoka prefecture tea market value chain Source: 社団法人日本茶業中央会 (平成18年) (This figure is translated from Japanese to English) Bangladesh. By 1903, there were 15 European planters in Northern Sylhet, 102 in Southern Sylhet and 26 in Habigonj district of Sylhet (Sana, 1989). At present Bangladesh has 162 tea gardens and among them Sterling Companies2) operate 28 gardens and 128 gardens are operated by Bangladeshi owners (National Tea Company, Bangladesh Tea Board, Private limited companies and proprietary owners). Besides, six gardens are operated by smallholders which are situated in the north-western part of Bangladesh. At present about 51,825 hectare of land is under tea cultivation in Bangladesh. This occupies around 46% of total area allocated by the government for the purpose of tea production. Due to the lack of appropriate initiative, 11,406 hectare of land is remained outside tea cultivation (Bangladesh Tea Board, 2004). It is understood that inefficient management and very old age bushes adversely affect tea production of the country. If this situation persists Bangladesh may become a tea importing country in the near future (Fig. 6). Aging of tea bushes drops tea production and this is a big threat for the sound growth of the tea industries of the country. Undertakings strategic decision may help to overcome this situation and make the tea production profitable. Fig.7 depicts the situation of tea bush depending on various age groups. The tea industry of Bangladesh comprises 82% of the area and these areas contain mature and old bushes. The old bush area comprises 42% of total area. Moreover, a large portion of the total cultivated land is left with late mature stage plants (Bangladesh Tea board, 2004). It seems that the smooth development of this industry may be at stake. Value chain structure of Bangladesh tea industry The value chain of the tea industry of Bangladesh concentrates on tea estates rather than on farmers cooperative mechanism. The quantity of production largely relies on large and small tea estates, which is quite opposite to Japan. Most of the tea estates in Bangladesh have tea manufacturing plant. Each tea estate is involved in the process of plucking tea leaves up to the delivery of product to the broker s premises. Most of tea estates do not manage the land under tea cultivation properly, that is why the quality of tea leaves becomes inferior. Besides, lack of appropriate handling practice and suitable withering of green leaves downgrade the quality of processed tea. In case of Japanese cooperative mechanism, before buying the green leaves from each tea farmer, quality measuring section of the each manufacturing plant grades the quality of green leaves adopting a sampling method. The price of the lot is fixed on the basis of quality. This type of rigorous procedure does not exist in Bangladesh. Each tea estate should go under the specified process (Fig. 8). After the bulk packaging on premises of the 62 横浜国際社会科学研究 第 11 巻第 4・5 号(2007年 1 月) (568) 70 60 1,000 ton 50 40 30 20 10 0 1980 1985 1990 Year 1995 2000 2004 Production Export Domestic consumption Fig: 6 Production, export and domestic consumption trend of Bangladesh tea Figure 6: Production, export and domestic consumption trend of Bangladesh tea Source: 社団法人日本茶業中央会 (平成18年) 45% 40% Percentage of area 35% 30% 25% 20% 15% 10% 5% 0% Immature Young Mature Old Age of the tea bush Bangladesh tea on on bush age group FigureFig: 7: 7Bangladesh teaarea areabased based bush age group tea estate, the processed black tea is sent to the broker s warehouse. The delivery and partial storage cost of the broker s warehouse is carried by the individual tea estate. The total value chain process is shown in Fig. 8. There is no cooperative farming system in Bangladesh which is quite opposite to Japanese industry. Cooperative manufacturing system helps to share the leaf production risk among farmers. In Bangladesh, tea gardens are owned by companies. Companies take all risks. In Japan, the smallholding farmers cooperative associations have their own manufacturing system and they have the capacity to meet the demand of the peak season. On the other hand, Bangladeshi owners do not have any powerful manufacturing capacity which can meet the demand of the peak season. In addition to this, Japanese smallholding farmer s cooperatives get fund from the cooperative association for replanting tea bushes. Farmers who can show good performances get extra monetary incentive after the selling of the aracha at the end of the year. This system does not exist in Bangladesh. In Bangladesh, black tea is sold through auction market by open bidding. In the auction market, on behalf of the Strategic Cost Management of Tea Industry (Sheikh Mohammed Rafiul Huque) (569) 63 Figure 8: Value chain of Bangladesh tea industry Table 1: Regression analysis of area under tea and the production level Model 1 r 0.898 r2 0.806 Adjusted r2 0.802 Std. Error of the Estimate 206161.4252 Coefficients Model 1 (Constant) YOUNG MATURE OLD Unstandardized Coefficients Beta −80805.240 3817.495 1941.185 656.394 t Sig. −2.928 6.189 9.025 4.993 0.004 0.000 0.000 0.000 Dependent Variable: PDN bidders, tea tasters judge the quality of tea from each lot by tasting samples and the price is determined accordingly. Due to the above mechanism in auction market, good quality tea gets higher price comparing to inferior quality tea. In the auction market both local and foreign buyers participate. Mahmud (2004) observes that the demand of tea in the market of Bangladesh is increasing by 3.5% each year and the supply of tea is increasing only by 1% each year. This high domestic demand is also increasing the level of price. If the price of tea gets higher than the expected price, foreign buyers may become reluctant to buy tea from Bangladesh and they may switch over to other foreign markets. Data analysis and strategic decisions Earlier parts of this paper discusses the current situation and problems of the tea industry of Bangladesh and its value chain structure and attempts to compare them with the tea industry of the developed country taking Japan as an example. This study adopts some statistical analyses to test the previous findings drawn from theoretical analysis. It is understood that a combination of theoretical and statistical analysis may provide strategic solution for the tea industry of Bangladesh. 64 横浜国際社会科学研究 第 11 巻第 4・5 号(2007年 1 月) (570) Table 2: Regression analysis of yield of all tea estates and price Model 1 R 0.517 r2 0.268 Adjusted r2 0.261 Std. Error of the Estimate 7.0283 Coefficients Model 1 (Constant) YIELD_HA Unstandardized Coefficients Beta 50.786 8.998E-03 t Sig. 28.111 6.396 .000 .000 Dependent Variable: PRICE Relationship between production and tea bush age This part at first concentrates on area under tea depending on different age groups of tea bushes and their relationship with tea production. The model is given below: Here, Here, Here, Here, Here, Yˆ � a �bˆ1x1 �bˆ2 x2 �bˆ3 x3 �� =Production Production level (PDN) Production level (PDN) level (PDN) Ŷ Production level (PDN) Production level (PDN) Ŷ === Young bush (YOUNG) [4-10 years] Young bush (YOUNG) [4-10 years] Young bush (YOUNG) [4-10 years] Young bush (YOUNG) [4-10 years] Young bush (YOUNG) [4 10 years] x1111 ==== x 2 = == Mature bush (MATURE) [11-40 years] x Mature bush (MATURE) [11-40 years] bush (MATURE) years] = Mature Mature bush (MATURE) years] bush (MATURE) [11 [11-40 40[11-40 years] 22 Mature x = Old bush (OLD_BUSH) [Above 41 years] 3 bush (OLD_BUSH) [Above 4141 years] bush (OLD_BUSH) [Above 41 years] = Old Old bush (OLD_BUSH) [Above years] bush (OLD_BUSH) x33= =Old [Above 41 years] The result of the regression analysis shows that the independent variables are significantly influencing the production of tea (Table 1). The high adjusted r 2 value (0.802) reflects the significance in the model. The beta coefficients of independent variables reflect that young bush (YOUNG) area which is significantly influencing the level of production (highest beta coefficient, 3817.50). This means that changing the young bush area by one unit will change the level of production by 3817.50 kg. In addition, mature bush (MATURE) area also have some significant bearing on production (1941.19 beta value). On the other hand, old (OLD) bush area provides very low level of production (656.39 beta value). The average yield of tea is around 1,255 kg. per hectare. The result of the above analysis suggests that the tea industries of Bangladesh need to transform their old and very old tea bushes into young tea and mature tea Here, Here, Ŷ = Production level (PDN) respectively. The regression model is given below: Here, (PDN) Ŷ = Production x1 =level Young bush (YOUNG) [4-10 years] Here, (PDN) Ŷ = Production xbush = Mature bush[4-10 (MATURE) x1 =level Young (YOUNG) years] [11-40 years] 2 Production level (PDN) x +=1941.185 Ŷ ==−80805.240 + 3817.495 + 656.394 x = Old bush (OLD_BUSH) [Above 41 year Young bush (YOUNG) [4-10 years] x 2 = Mature 3bush (MATURE) [11-40 years] 1 x1 = Young bush (YOUNG) [4-10 years] = Old bush (OLD_BUSH) [Above 41 years] x 2 = Maturexbush (MATURE) [11-40 years] 3 bushes and this may significantly increase the yield of the two types of bushes at around 3817.50 kg. or 1941.19 kg. x 2 = Mature (MATURE) [11-40 years] Relationship between management of teabush estates (yield) and Price (quality) x3 = Old bush (OLD_BUSH) [Above 41 years] x3 analysis = Old bush [Above 41 years] it (OLD_BUSH) is clear that for efficient production of tea, young and mature tea areas From the above regression are essential for Bangladesh tea estates. High yield tea gardens3) have better bush management comparing to poorlymanaged gardens4). This may have a positive linkage with the price of tea. In the following it is examined that whetherthere exist any relationship between high yield tea gardens and the price of tea. The analysis of this model is shown below: Strategic Cost Management of Tea Industry (Sheikh Mohammed Rafiul Huque) (571) 65 Yˆ � a �bˆ x �� Here, Here, Price (PRICE) Ŷ = Production level (PDN) (YOUNG) [4-10 years] =Young Yield per hectare (YIELD_HA) perbush hectare (YIELD_HA) x1 ==Yield x 2 = Mature bush (MATURE) [11-40 years] x3 = Old bush (OLD_BUSH) [Above 41 years] result of the regression analysis shows that yield has a significant influence on price (Table 2). Though the r2 The value (0.268) is not very high, moderate relationship exists between yield and price. It seems other factors have influence on the low r2 value. The beta coefficient indicates that if yield per hectare (YIELD_HA) increases by one unit, price will increase by 8.998E-03 unit. It can be concluded from this analysis that good land management has a direct link with the production Here,price. The model is given below: of good quality tea and tea produced by well managed gardens fetch higher Ŷ = Production level (PDN) Here, Production level (PDN) + 8.998E-03 Ŷ ==50.786 x1 = Young bush (YOUNG) [4-10 years] x1 = Young bush (YOUNG) years] bush (MATURE) [11-40 years] x 2 [4-10 = Mature x 2 = Mature bush (MATURE) [11-40 years] Strategic decisions and value chain modification x3 = Old bush (OLD_BUSH) [Above 41 years] x3 = Old bushgardens (OLD_BUSH) [Above 41 level years]of production. The strategic to increase their Strategic decisions are needed for the poorly-managed alliance of the poorly-managed gardens can be an option to improve their yield, production and quality of leaves. In this regard, the model of Japanese tea industry can be replicated with some modifications. The modification is necessary to make it more applicable for the tea estates of Bangladesh. In Japan, cooperative farming model is widely practiced among the tea farmers (Fig. 5). Moreover, Japanese model can not be adopted without a modification due to the sizes of the gardens are quite big in the developing countries like Bangladesh. It seems that strategic cooperative alliances among the tea estates may be a better option for the tea industry in Bangladesh. Huque (2006) explains the possibility of alliance among the closely located tea gardens situated in the south-eastern part of Bangladesh. In that case, small gardens operate as leaf growers and there exists a central leaf buying unit which is operated by the government. The responsibility of the central leaf buying unit is to buy leaves from the growers and sell them to the central leaf processing unit. The two stage handling of green leaves actually reduces the quality of made tea5) and which in turn reduces the price of tea in the auction market. The strategic alliance model is a combination of Japanese model and the model which is proposed by Huque (2006). Huque (2006) proposes a two stage handling green leaves. In the present model, central leaf manufacturing facility will have a buying place equipped with quality measurement device. Leaf producing firms will carry the green leaves until central leaf processing plant. That machine measures the quality of green leaf before buying from the strategic growers and set the price accordingly depending on the grades of the leaves. As the quality of green leaves deteriorate very fast, proper handling is necessary for maintaining the quality. This proposed model is adopted would improve the situation which may maintain the quality of green leaves due to one level handling and at the same time encourage the high performing tea gardens to receive elevated price. This proposed model uses a common leaf processing facility established by strategic cooperative alliance farms. This new model, if adopted, can also reduce fixed cost related to the establishment of multiple factories. Tea gardens either can use their existing machineries for the establishment of a manufacturing unit or can share their common fund for this purpose. Besides, cooperative alliances model can use their common fund for land development and maintenance of tea bush which may solve scarcity of resources. This proposed model may change the value chain structure of the tea industry of Bangladesh (Fig. 9). In current value chain system of Bangladesh each tea estate is responsible from the stages of plucking to delivery of the product to the brokers. In the proposed value chain plucking and leaf carrying type of primary activity cost is shifted to leaf producing company. 66 (572) 横浜国際社会科学研究 第 11 巻第 4・5 号(2007年 1 月) Figure 9: Strategic cooperative alliances Table 3: Low yield tea estates comparison Yield below 1000 kg./hectare (62 tea estates) Number of tea estates Tea area in hectare Number of tea estates Suitable extension area in hectare Yield below 600 kg. per hectare 28 tea estates Large Small gardens gardens Below 200 Above 200 21 7 3 360 16 400 Yield 601 1000 kg. per hectare 34 tea estates Large Small gardens gardens Below 200 Above 200 13 21 15 400 3 375 Source: Bangladesh Tea Board (2004) This may help the strategic alliance firms to concentrate more on production and producing better quality leaves by nurturing and maintaining the tea bushes. Currently, tea estates are reluctant to uproot their old tea plants due to the risk of lowering the production of tea. The proposed model reduces this type of risk as few gardens will supply the green leaves without hampering the production. The cooperative alliance model can keep the production level to an optimum level. In the Japanese cooperative association, profit sharing system is common among the farmers depending on the performance. Replication of this type of incentive system may enhance the strength of the strategic alliance tea gardens. Bangladesh Tea Board will monitor the implementation process of the proposed model. They have the supreme authority of evaluating performance level of the tea estates and they also give lease of the land to the tea estates. Besides they put comments to the banks about the level of performance of the tea estates while sanctioning loans. Due to the evaluation authority of Bangladesh Tea Board, they may encourage the low performing tea estates to form a strategic alliance among them to improve their level of performance. This model of strategic cooperative alliances is applicable to both large and small gardens who have intention of increasing production and making good quality tea with low cost and risk. As this alliance uses a common production facility, manufacturing cost should be lower. This model stresses that one should identify small tea gardens (below 200 Strategic Cost Management of Tea Industry (Sheikh Mohammed Rafiul Huque) (573) 67 Table 4: Regression result of production and tea area of well and poorly-managed tea estates Well land managed Tea estates Poor land managed tea estates Above 1500 0.973 0.970 292.583 2082.21 (0.006)* 1690.89 (0.000)* 1654.13 (0.000)* From 601 1000 Below 200 hectare 0.917 0.892 36.95 1063.53 (0.001)* 907.74 (0.000)* 642.30 (0.001) Yield per hectare Tea area r2 Adjusted r2 F value Young Unstandardized beta coefficient** Mature Old Dependent variable: Production in kg. * Parentheses represent the significance level ** Immature bush area has been omitted due to insignificant value and high multicollinerity 900 Tea area in hectare 800 700 600 500 400 300 Yield from 601-1,000 kg. and tea area below 200 hectare SCA gardens 200 100 0 Immature Young Mature Old Age of tea bush Figure 10: Tea area of SCA gardens and poorly-managed tea estates hectare) situated in close proximity with low yield, as uprooting and maintaining of tea bush is easier in these gardens. These gardens have less complexity in management. It is understood that after the successful implementation of this approach, large tea gardens may be inspired to adopt this approach. Table 3 shows that 62 tea estates in Bangladesh produce less than 1,000 kg. tea per hectare. These gardens need to improve their performance by adopting the policy of strategic alliance model mentioned earlier. The yield of the 28 gardens of the country is below 600 kg./hectare. There are 21 gardens in this group in the country which have garden size with less than 200 hectare each. It is understood that strategic cooperative alliances could be start from these small gardens depending on the close location among them. It is also understood that after the successful implementation of this approach, other tea estates (yield 601 1000 kg. per hectare) with low yield may be inspired to adopt this model. 68 (574) 横浜国際社会科学研究 第 11 巻第 4・5 号(2007年 1 月) Strategic cooperative alliance (SCA) model and cost implication The previous part of this paper focuses on the strategic solution of tea industry in Bangladesh and proposes SCA model as a solution for the tea industry. It is needed to compare the cost implication of the proposed model in poorlymanaged tea estates. In this regard, it is needed to assume that poorly-managed tea estates will be functioned like wellmanaged tea estates considering land management, cost and price aspects after the implementation of SCA model. It is understood from the regression in Table 1 that young and mature bush area are essential for Bangladesh tea industry. It is found from the survey that yield of the least developed tea estates in Bangladesh is below 600 kg. That is why 600 kg. is considered as point of demarkation between operating and non-operating gardens. It is needed to understand whether this scenario differs in well and poorly-managed tea estates (yield from 601 1000 kg. and tea area below 200 hectare). The results of the regression analysis in Table 4 depict that tea area in both well and poorly-managed tea estates significantly affect production. The high adjusted r2 values (0.970 and 0.892) reflect the significance of the models. The beta coefficients of independent variables reflect that condition of well-managed tea estates is much better than poorlymanaged tea estates. The beta coefficients of young bush area (YOUNG) in well-managed and poorly-managed tea estates are 2082.21 and 1063.53 respectively. This means that changing the young bush area by one unit will change the level of production by 2082.21 kg. and 1063.53 kg. in well and poorly-managed tea estates respectively. The result of the above analysis concludes that the condition of poorly-managed tea estates will be improved after introducing SCA model. Fig. 10 simulates the situation of SCA gardens after the implementation of proposed model and compares the situation with poorly-managed tea estates. The simulation model tries to maximize young bush area and minimizes old bush area in SCA gardens and compares the situation of SCA gardens with poorly-managed tea estates after five years of implementation. It is assumed that the successful implementation of this model would increase production level significantly. Besides, young bush area will also be constant source of good quantity green leaves in the mature stage. From the above analysis it is clear that SCA model can improve the condition of poorly-managed tea estates. At this stage, it is needed to understand the financial implication of this model which can motivate them to form this kind of alliances. Table 5 compares the financial implication of SCA gardens and poorly-managed tea estates. The table uses data related to production and land utilization from Table 4 and Fig. 10. In addition, data related to costs and prices were collected by primary survey among the tea estates and tea auction market in Bangladesh. It assumes that other factors related to cost and price will remain constant for few years (five years). Five years is considered in this analysis due the simulation model analyzes the situation of SCA gardens after five years. Table 5 depicts that average unit variable cost in poorly-managed tea estates is 22.55 Tk6). and average total fixed cost is 10,549,630 Tk. On the other hand, average unit variable cost in well managed tea estates is 19.49 Tk. and average total fixed cost is 9,876,719 Tk. In addition to average fixed cost, SCA gardens have to incur depreciation cost of re-planting new tea plants in the old bush area. From the financial analysis in Table 5 it is apparent that profit of SCA gardens is around twelve times higher than poorlymanaged tea estates. In addition, another strategic cost accounting methods, target costing approach, is used to evaluate the condition of SCA gardens which is different from direct costing approach. Well-managed tea estates average price is considered as target price for the SCA gardens and target profit in considered as 15%, which in industry average. Target cost of the SCA gardens is derived by deducting target profit from total sales. The calculation is given below: Target price – Target profit = Target cost 104,352,901 Tk. (Unit cost is 65.69 Tk. ) – 13,087,538 Tk. = 91,265,362 Tk. (Unit cost is 56.45 Tk.) It is derived from Table 5, direct costing approach gives higher profit comparing to target costing approach. It can be concluded that both approaches (direct costing and target costing) give higher profit to the SCA gardens comparing Strategic Cost Management of Tea Industry (Sheikh Mohammed Rafiul Huque) (575) 69 Table 5: Strategic cost analysis of SCA gardens and poorly-managed tea estates Target costing approach for SCA gardens Young bush area (Hectare) Production change/Hectare Total production Sales price**** Unit cost**** Unit variable cost**** Total sales Total variable cost Total fixed cost Depreciation cost for re-plantation** Total cost Profit/Loss SCA gardens using variable costing approach 763 2,082 kg.* 1,588,566 kg. (1,589 ton) 65.69 56.45 104,352,901 Tk. (102,615,870 Tk./40 years***) = 2,565,397 Tk. 91,265,362 Tk. 13,087,538 Tk. 763 2,082 kg.* 1,588,566 kg. (1,589 ton) 65.69 19.49 104,352,901 Tk. 30,961,151 Tk. 9,876,719 Tk. (102,615,870 Tk./40 years***) = 2,565,397 Tk. 43,403,267 Tk. 60,949,633 Tk. Poor land managed tea estates using variable costing approach (Yield 601 1000 kg. and tea area below 200 ha.) 369 1,064 kg.* 392,616kg. (392 ton) 62.70 22.55 24,617,023 Tk. 8,853,491 Tk. 10,549,630 Tk. 19,403,121 Tk. 5,213,902 Tk. * Data has been taken from Table 4 [763 hectare (old and very old bush area)*13,449 bushes/hectare]*10 Tk./ bush = 102,615,870 Tk. Maintain until end of mature stage (40 years) **** 1 US$=60.21 Tk. ** *** to poorly-managed tea estates. It is also apparent from both analyses, SCA gardens enjoy higher profit due to high yield, good land management, high price and low cost comparing to poorly-managed tea estates. Conclusion Agriculture commodities (like tea) in the developing countries are facing price competition. Poor land management, plucking inefficiency and high manufacturing cost which may be observed in the value chain, hinders their growth. It can be concluded from the study that the managers of the tea estates of Bangladesh are reluctant to maintain the tea bushes which further reduces tea production and abruptly affects yield and quality of green leaves. This in turn raises cost in the value chain and lessens price of tea in the auction market. About 40% of tea estates of the country have yield below 1000 kg./hectare. Among these low yield gardens, yield of around 50% gardens is less than 600 kg./hectare though they possess large areas of land for tea cultivation. Moreover, these low yield gardens also receive lower price comparing to high yield gardens due to the poor quality of green leaves which they produce. The regression analysis shows that if the low performing gardens possess more young tea bushes, production level can be increased up to 3,818 kg./hectare keeping other variables constant. In this respect old tea plants of these gardens should to be uprooted and new plants must be planted soon. But due to poor land management and worry of lowering production, this type of initiative is not taken by the management of the low performing gardens. Strategic cooperative alliance model which is developed in the light of Japanese cooperative model can be a solution for these poor performing gardens. This model, if adopted, may significantly reduce the problems of land management and at the same time strategic alliance farms can enjoy benefit of using the common fund for bush management and improve the overall manufacturing facility, which may further improve the quality of finished tea. It is also found from financial analysis that SCA gardens will obtain higher profit after successful 70 (576) 横浜国際社会科学研究 第 11 巻第 4・5 号(2007年 1 月) implementation of the model. In addition young bush area will not only give high yield during young stage, but also be a constant source of good quantity and high quality of green leaves during mature stage of the plants. This will certainly boost this industry to secure a strong position in the world tea markets. References An environmental Educational Program of the Prague Post Endowment Fund. (2003). An environmental Educational Program of the Prague Post Endowment Fund, 4 (13), Retrieved April 16, 2003, from http://www.Praguepost.cz/ppEF/13SC030416.pdf. Ariyawardana, A. (2003). Sources of competitive advantage and firm performance: The case of Sri Lankan value-added tea producers, Asian Pacific Journal of Management, 20, 73 90. Bangladesh Tea Board. (2004). Statistics on Bangladesh tea industry. Moulvibazar: Bangladesh Tea Board. Bangladesh tea market annual report. (2004 2005). National Brokers Limited. Chittagong: National Brokers Limited Bruinsma, J. (Ed.). (2003). World agriculture: Towards 2015/2030 an FAO perspective. London: Earthscan Publications Ltd. Chang, C. J. & Hwang, N. R. (2002). The effects of country and industry on implementing value chain cost analysis, The international Journal of Accounting, 37, 123 140. Chen, Y. S. A.; Romocki, T. & Zuckerman, G. J. (1997). Examination of U.S. based Japanese subsidiaries: Evidence of the transfer of the Japanese strategic cost management, The International Journal of Accounting, 32(4), 417 440. Choudhury, M. S. H. (1989). Tea growing. Dhaka: Ananda Printers. Dess, G. G. & Davis, P. S. (1984). Porter s (1980) Generic strategies as determinants of strategic group membership and organizational performance, Academic of Management Journal, 27, 467 488. Gilbert, X. & Strebel, P. (1987). Strategies to outpace competition, Journal of Business Strategy, 8(1), 28 37. Hall, W. (1980). Survival strategies in a hostile environment, Harvard Business Review, 58(5), 75 85. Hambrick, D. (1983). High profit strategies in mature capital goods industries: A contingency approach, Academy of Management Journal, 26, 687 707. Hazarika, C and Subramanian, S. R. (1999). Estimation of technical efficiency in the Stochastic Frontier Production Function model- An application to the tea industry in Assam, Indian Journal of Agriculture Economics, 54 (2), 201 211 Hibiki-en. (2006). Four seasons of green tea. Retrieved July, 24, 2006, from http://www.hibiki-an.com/readings/four-seasons-ofgreen-tea.html Huque, S. M. R. (2006). Cost factors leading to strategy formation of Bangladesh tea industry. Yokohama Journal of Social Sciences, 10(6), 39 56 International Tea Committee. (2003). Annual Bulletin of Statistics. London: International Tea Committee Japanese tea production. (2006). Japanese tea production at Shirakata Denshiro Shoten, Inc. Retrieved July, 25, 2006, from http:// www.shirakata.co.jp/eng/koutei.html Kato, Y. (1993). Target costing support systems: lessons from leading Japanese companies. Management Accounting Research, 4, 33 47. Li, F. & Whalley, J. (2002). Deconstruction of the telecommunication industry: from value chains to value networks, Telecommunications Policy, 26, 451 472. Mahmud. M. (2004, January 5). Tea in a new brew. The Daily Star, p.1. Retrieved January 5, 2006, from http://www.thedailystar. net/2004/01/05/d4010501022.htm Maitland, C. F., Bauer, J. M. & Westerveld, R. (2002). The European market for mobile data: evolving value chains and industry structures, Telecommunications Policy, 26, 485 504. Porter, M. E. (1985). Competitive advantage, New York: The Free Press Sana, D. L. (1989). Tea science. Dhaka: Ashrafia Boi Ghar Shank, J. K. (1996). Analyzing technology investments-from NPV to strategic cost management (SCM). Management Accounting Research, 7, 185 197. Shank, J. K., & Govindarajan, V. (1992). Strategic cost management: the value chain perspective. Management Accounting Research, 4, 177 197. Shank, J. K., & Govindarajan, V. (1993). Strategic cost management. New York: The Free Press Strategic Cost Management of Tea Industry (Sheikh Mohammed Rafiul Huque) (577) 71 The history of tea. (2003). Retrieved July 18, 2006, from http://www.stashtea.com/facts.htm 社団法人日本茶業中央会.(平成18年).茶関係資料.東京:社団法人日本茶業中央会 Notes 1) Aracha is simply green tea that has been freshly picked at near-by farms and steamed immediately to prevent oxidation. Upon steaming the tea gets rolled and dried. In Japanese, this tea is called aracha (Japanese tea production, 2006) 2) British companies 3) Yield above 1,500 kg. per hectare 4) Yield below 1,500 kg. per hectare 5) Processed tea 6) Taka [セイク モハメド ラフィール ハーク 横浜国立大学大学院国際社会科学研究科博士課程後期]