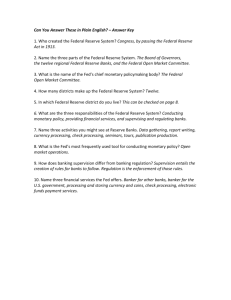

THE FEDERAL RESERVE SYSTEM DISCUSSED: A comparative

advertisement