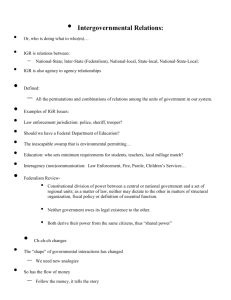

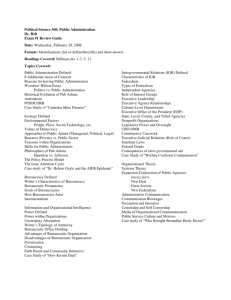

INTERGOVERNMENTAL RELATIONS IN THE EARLY 21ST

advertisement