Defining dual diagnosis of mental illness and substance

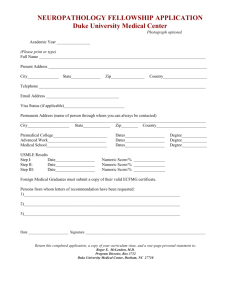

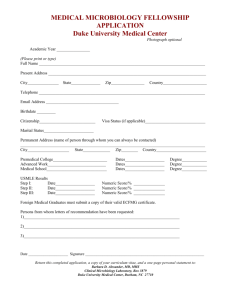

advertisement