research digest - Fitness for Life

advertisement

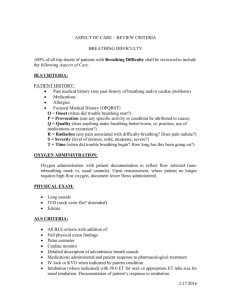

RESEARCH DIGEST Mark A. Merrick, PhD, ATC, Column Editor H -= OW MANY of your athletes wear nasal dilator strips during competition or practice? How many of your coaches have provided these strips or encouraged you to provide them for your athletes? We now see them everywhere. In fact, I saw some 10-year-old football players in a junior football league wearing them not long ago. Are these devices really a benefit to our athletes, or are they just a fad? Over the past few years, researchers have begun examining this question, and we are now beginning to find some answers. BreatheRightB nasal strips are by far the most common external nasal dilators on the market. Bruce Johnson, the inventor of the BreatheRight strip, originally developed it as a means of relieving his nasal breathing difficulties caused by a deviated septum (CNS). He applied for a patent in 1 991, and the strips were licensed to CNS Inc. in 1992. From there, the marketing blitz took off. BreatheRight strips are now "official locker room products" of the NFL, the NHL, and Major League Soccer. BreatheRight even has an "advisory panel" of professional athletes including the NFL's Jerry Rice and the NHL's Peter Bondra (CNS). Although the marketing and hype have been widely successful, the real question is, Do these strips provide any benefit to athletes? There are two predominant theories explaining a potential physiological mechanism by which nasal dilators might be useful to athletes (O'Kroy). First, they might decrease airway resistance and therefore increase minute-ventilation (the volume of air breathed per minute) and the partial pressure of oxygen (PO,) in the alveoli, leading to greater diffusion of oxygen into the bloodstream and more oxygen being delivered to working muscles (O'Kroy). Second, the reduction in nasal airway resistance could make breathing easier and potentially reduce the oxygen cost of breathing. Because breathing muscles woul _-----.-- g m r e oxygen would be available for the exercising muscles (Harms). In addition to these physiological mechanisms, the perception of easier breathing might also be a psychological benefit. __lly ---- 2001 Human Kinetics. AT1 6(2). pp. 42-43 4 2 1 MARCH 2 0 0 1 ATHLETIC THERAPY TODAY Marketing hype and potential mechanisms aside, there have been a number of good double-blind, placebocontrolled studies involving nasal dilator strips in recent years. From these studies, a number of important findings have emerged. First, nasal dilator strips do appear to improve nasal breathing. The nasal valve, a narrowing in each nostril, is the main restrictor of airflow through the nose. Researchers have shown that in many individuals, external nasal dilator strips increase the cross-sectional area of the nasal valve and thereby the volume of air that passes through the nose (Griffin, O'Kroy, Seto-Poon). Researchers have also observed a decrease in nasal airflow resistance in some individuals wearing nasal dilator strips (O'Kroy, Seto-Poon). Altering airflow resistance is an important point, but ultimately we are more concerned with whether or not the strips can improve athletic performance. During rest, we inhale approximately 80 % of the air we breathe through the nose, but during exercise this drops to roughly 25-40 % (O'Kroy). The change from nasal to oral breathing occurs because we need to dramatically increase our minute-ventilation during exercise, and nasal breathing cannot supply a large enough volume of air. Seto-Poon and colleagues demonstrated that using external nasal dilator strips delays the switch from nasal to oral breathing by roughly 15 % . They concluded that these strips do indeed promote nasal breathing but that the delay in switching to oral breathing was small. In another set of studies, researchers have shown a variety of performance improvements with nasal dilator strips. Griffin and colleagues reported that during submaximal exercise, the strips decreased exercise heart rate, perceived exertion, ventilation, and VO, when compared with a placebo. All of these would indicate that the participants did not have to work as hard to maintain their level of exercise. Similarly, Gehring and colleagues showed that external nasal dilator strips reduced the work of breathing during maximal exercise in 11 of their 1 9 participants. Harms and colleagues found that increased work of breathing can reduce blood flow to active locomotor muscles. One would certainly suspect that devices that ATHLETIC THERAPY TODAY Chinevere TD et al., 1999,J Sport Sci. 17:443-447. CNS Inc., www.breatheright.com (October 30, 2000). Gehring J M et al., 2000, JAppl Physiol. 89:1114-1122. Griffin JW et al., 1997, Laryngoscope. 107:1235-1238. Harms CA et al., 1998, J Appl Physiol. 85:609-618. O'Kroy JA, 2000, Med Sci Sports Exerc. 32: 1491-1495. Seto-Poon M, 1999, CanJ Appl Physiol. 24538-547. lessen the work of breathing would allow better blood flow to other exercising muscles. W h a t We Don't Know As you have come to expect in this column, nothing is entirely straightforward in research-for every article showing an effect, there are other studies showing none. Nasal dilators are no exception. In a recent article, O'Kroy and colleagues examined the effect of external nasal dilator strips during exercise. Because some studies have shown that not all participants have breathing improvements with nasal dilator strips, O'Kroy and colleagues used only participants who reported that they found it easier to breathe while wearing the strips. During a maximal exercise test, the nasal dilator group had no improvements in V02,,x, maximal minute-ventilation, perceived exertion, work rate, or end-tidal (after breath) 0, or CO, levels. Submaximally, they observed no improvements in VO,, heart rate, minute-ventilation, end-tidal 0, or CO,, or perceived exertion. Chinevere and colleagues also observed no improvement in cardiorespiratory variables during five maximal treadmill tests while participants wore nasal dilators. So whom do you believe? Most researchers have observed increases in nasal breathing with nasal dilator strips. On the other hand, a slight majority of articles show no improvements in cardiorespiratory variables. I t appears that in some cases, for some people, these strips might have benefits, but clearly this is not always the case. I MARCH 2001 1 43