Reflexivity and the Whole Foods Market consumer

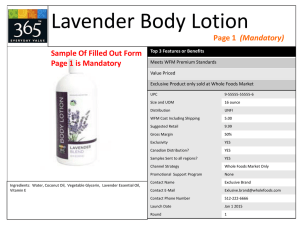

advertisement