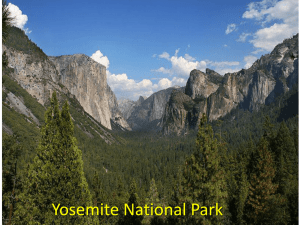

Federal Land Management Agencies

advertisement